In 1981, two San Diegans were diagnosed with AIDS. The number doubled the following year. Five years later, more than 700 had been diagnosed and nearly 400 had already died.

As we found in our February 1988 issue, the health care community was flying blind with very little funds or support. Because the disease was still widely perceived as affecting only drug users and the gay community, it carried a heavily negative social stigma, which left doctors in a difficult position regarding disclosure. In most other circumstances, the law held that a patient’s spouse had a right to know about health conditions that place them at risk. But as Dr. Lawrence Schneiderman, then an internist and professor of ethics at UC San Diego Medical School, told the magazine:

“Of course, there’s no way homosexuals can legally marry each other. So once again society has taken the moralistic stance that spouses deserve to be told, but lovers of any sex or other relationship do not deserve the same type of protection.”

Schneiderman, now a professor emeritus at UCSD, remembers that medical professionals and the general public reacted ferociously because of extreme fears. “Until the American Medical Association issued ethical guidelines in 1987, some physicians and surgeons justified avoiding AIDS patients. That same year, a family who tried to keep their HIV-positive hemophiliac boys in school had their house torched to the ground.”

Fortunately, public perception and medical outlooks gradually improved. Rock Hudson and Liberace were among the first high-profile celebrities to contract AIDS; the former revealed this publicly only shortly before his death in 1985, and it would take a 1987 autopsy report to confirm the latter.

“By contrast,” Schneiderman says, “four years later, Magic Johnson announced he was HIV positive as soon as he learned of it and is still alive and robustly active. Today there are over a hundred treatment protocols for the condition.”

Of course, these treatments dovetail into a problem shared among patients with all manner of chronic conditions—the unsustainable cost of medical care. “In 1998, per person health care costs of AIDS patients amounted to about $50,000. Today, lifetime costs per patient are between $300,000 and $500,000.”

New diagnoses in San Diego County peaked in 1990 at 1,300, and have decreased nearly every year since. Thanks to comprehensive sex education and powerful antiretroviral therapies, HIV is no longer the death sentence it once was. But nearly half of the 13,200* San Diegans currently living with HIV can remember a time when moral panic left little room for hope.

*As of 2014

PARTNER CONTENT

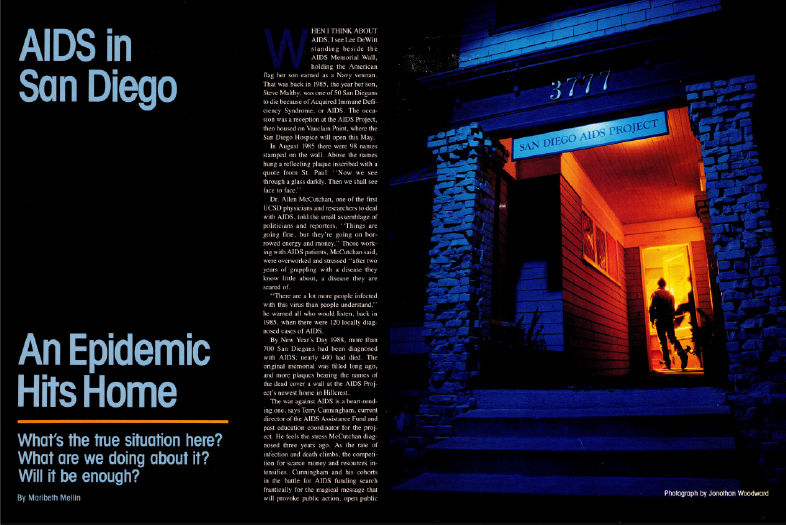

From the Archives: What San Diego’s AIDS Epidemic Looked Like in 1988