Café X: By Any Beans Necessary, isn’t just a coffee shop. It’s a vibrant celebration of Black community. It’s a worker cooperative, founded by Khea Pollard and her mother Cynthia Ajani as a pathway to economically empower the Black community in San Diego. At Café X, it’s the workers that own a piece of the business, not a single owner or detached shareholders.

Pollard, who has a master’s in nonprofit leadership and management from the University of San Diego, was assigned to develop a passion project as part of a leadership fellowship program called RISE San Diego. She asked herself, “How do we build something in our community that can withstand economic downturns by collectively pulling together our resources, activating our skills and talents, and investing in preparing the next generation of leaders?” Café X, with its model of cooperative economics, and its peach cobbler cinnamon rolls, was the answer to that question.

As a policy advisor for the county of San Diego, Pollard started to see the need for building power economically, particularly in Southeast San Diego. “There was at one point a plethora of Black businesses that have dissipated over time as Black people moved out of San Diego or California,” she says. “They’re unable to keep up with the cost of living.”

For Pollard, the days of a thriving and cohesive Black community in San Diego are barely a memory. But her mother, whose parents moved here from St. Louis and Dallas when they were young children, recalls a time when Black San Diego spanned the West Downtown Area, Sherman Heights, Logan Heights, Lincoln Park, and Valencia Park. Black businesses were blossoming in Southeast San Diego, with hair salons and barber shops, clothing stores, restaurants, and street fairs that celebrated Black culture and jazz.

“We see that in spurts now, but it used to be constant,”Ajani says. “Growing up in Southeastern San Diego was more than just the eight blocks that they’ve now designated a ‘Black Arts District.’ Now I hardly know how to identify where the Black community is,” she says. “We’re all dispersed.”

Café X is an attempt to stitch together threads of community that have unraveled, to shore up Black wealth that has been lost and stolen and gained back and lost and stolen again. The name of the shop takes its inspiration from one of Malcolm X’s most recognizable speeches: “We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary.”

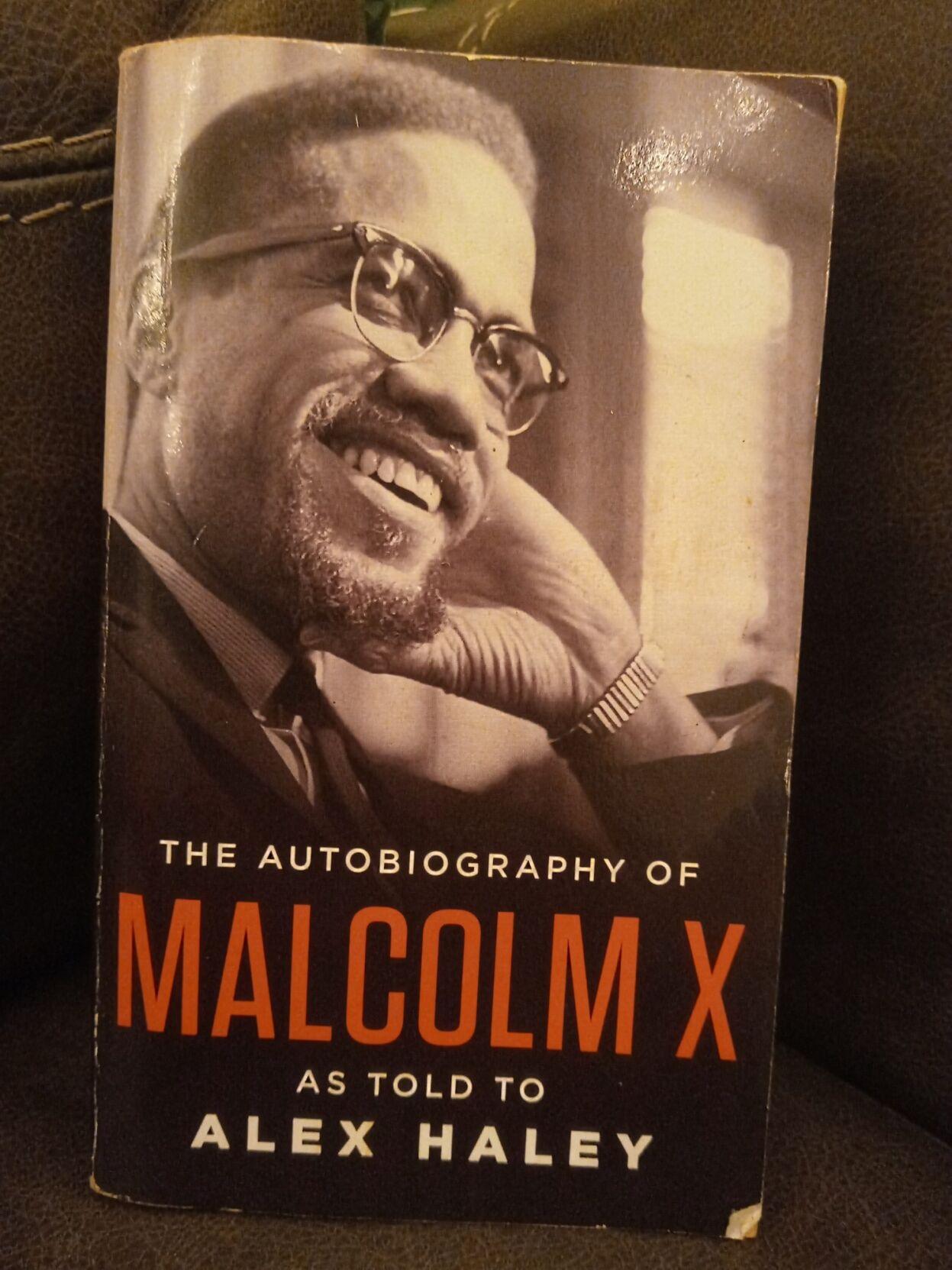

A copy of Malcolm X’s autobiography, which was a gift to Pollard from her father.

Pollard still has the worn copy of Malcolm X’s autobiography that was gifted to her by her father. Growing up, she returned to the book many times, drawn to the Muslim civil rights leader’s story and journey from drug dealer to incarcerated person to Nation of Islam leader to a universalist and Pan-Africanist. But most of all, she was drawn to his fierce commitment to autonomy and self-sufficiency for Black people.

“He was so serious about self-determination for the Black community and the ability to choose, the agency and the respect and the dignity that is inherently in us,” Pollard says. “Most people think about self-defense when they think of Malcolm X, but when I think of him, I think of his intense love for Black people, Black culture. I think of how he wanted to build up Black economics.”

It is her own family’s experience with the rollercoaster of financial survival while Black — especially in such an apocalyptically gentrified area as San Diego — that informs Pollard’s work. Her great-aunt owned a business and her great-grandmother owned a home in Southeast San Diego. But Pollard’s grandmother had a stroke and brain hemorrhage, which meant Ajani needed to sell the home to pay for her mother’s care.

“My mother sold the house to pay for my grandmother to live,” Pollard says. “It’s disenfranchisement. These are the conditions that make it impossible for families to have assets in that community, to further their deep roots in that community.”

Café X curates goods from Black-owned businesses all over the country, has an internship program, is exploring a model of worker and consumer ownership, and is pursuing ownership of their own space. But perhaps Café X’s most ambitious project yet is the Black Women’s Resilience Project, a universal basic income pilot program aimed at providing a standard quality of life for low-income Black women. It is a project that both Pollard and Ajani recognize is built on the labor of Black women who fought tirelessly for this ideal in generations past.

“What I’m doing isn’t new,” Pollard says. “It’s a continuation of a legacy from Black women like Johnnie Tillmon and Ruby Duncan in the Welfare Rights Organization who said, ‘We don’t have equal access to the public benefits we’re entitled to. We’re going to challenge governments to provide what we should have access to as women, as mothers, as people in this neighborhood and in this community.’”

Khea sits and shares an iced coffee with her mom, Cynthia Ajani. The two women co-own Café X together.

Photo Credit: Ariana Drehsler

Pollard points out that as Black women won gains in the welfare rights movement, the pushback was forceful. “When we finally did start to get access in the ‘60s, there was a crackdown on the programs. Stereotypes like the welfare queen emerged, characterizing public benefits recipients as lazy, incompetent, unintelligent.” Pollard says. Ajani can remember the effects of this in her own life. After her parents split, her homemaker mother was subjected to the welfare system as a Black woman. “The social worker came down from on high and told us how to live and what to do,” she says. “It was the most dehumanizing experience of my life.”

Detractors of universal basic income often claim that if people in poverty are simply “given” money, it will deter them from wanting to work. To that, Pollard and Ajani simply cite the facts. “The Stockton Universal Basic Income Experiment’s ground-breaking research said, ‘People who are on these programs actually work more. They’re not lazy.’ Pilot programs like the Magnolia Mother’s Trust in Jackson, Mississippi and Atlanta’s I.M.P.A.C.T. program showed that universal basic income increased someone’s ability to work and go back to school,” Pollard says.

Still, the question has to be asked. So what if people don’t work, don’t want to work, or can’t work? Does one’s ability to live a good life have to be tied to their willingness to work a job? Pollard agrees – it doesn’t really matter. “That’s exactly what I believe and exactly what a lot of people in this movement believe. We quote work statistics because that seems to be where public discourse gets jammed. People get all messed up about it. So we try to dispel that,” she says.

“But also, what is this attachment to a job, any job?” Pollard continues. “Welfare to work does not help people reach their ultimate destination. It’s making sure you keep the engine chugging.”

PARTNER CONTENT

Pollard says that the insistence that Black people must work to earn life is “undoubtedly” rooted in slavery, and is ultimately a destructive idea. “We should be able to dream. We should be able to rest. We should be able to have a plethora of choices available to us. That’s what guaranteed income is all about. It’s about not only providing an economic floor through which no one can fall, it’s about changing the idea that your worth is in how much you produce.”

For Pollard, human worth lies in the mere fact of their existence. “Your value is innate and inherent,” she says.