You’re broadly hailed as a “literary badass” with a “rock ’n’ roll heart…”

…yeah, what’s that?

That’s you, apparently! How did you get that name?

I think the particular critic who first wrote that was taken with my book of short stories about blue-collar, rough-andtumble boys, who might have been me at one time. Part of it also comes from my book The Devil’s Highway [the Pulitzer Prize finalist], when I talked the US Border Patrol into letting me investigate a death event. It was fraught with threat and danger. The rock ’n’ roll heart, I think, is because I was a working San Diego boy. I learned everything through Bob Dylan or Led Zeppelin and thought I wanted to be a musician. In high school and beyond, I exercised that by writing lyrics for local rock bands. If you talk to my friends from Clairemont High School, I was the guy with a notebook. I was always writing.

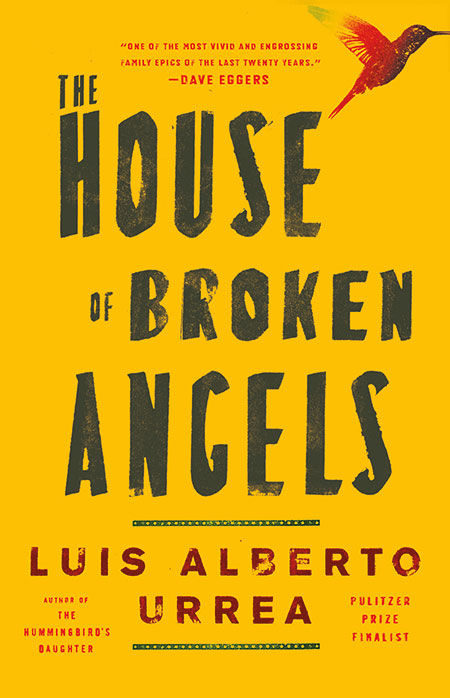

‘Literary Badass’ Luis Alberto Urrea on His New Cross-Cultural Book

How did your own life inspire the book?

I came back to San Diego to attend my brother’s birthday party, which he knew was his last. It was so full of energy and history—a really interesting view into a Mexican American family who’s been in San Diego for 50 years. Right after the party, my brother died. The sorrow inspired this story from the deepest parts of my soul—a celebration of family, and history, and trying to come to terms with regret. Also, it’s honestly a love song to San Diego. The fictional family in the novel comes from La Paz, but it’s set in an invented neighborhood that I’d put along the 805, somewhere between Chula Vista and National City.

Why is it important to tell this story now?

It’s timely by accident of events. The book is being released March 6, the day after DACA is supposed to run its course. This is a really complicated time with conversations about immigrants and who’s American. I tried to make it a story that both sides of the aisle could read. The elder brother is a Republican. The younger brother is a self-satisfied Democrat like me. I’m trying to address the national issue in that the book is about a family who has been here almost 60 years; they just happen to be from another culture. So, what does it mean to be an American? Who are we? Who am I? I came from Tijuana, settled in Logan Heights, moved to Clairemont in fifth grade.

Given your binational upbringing, do you feel it’s your duty as a “border writer”—as you’re also frequently tagged—to shed light on these issues?

I don’t like being tagged that. It’s because of my last name that I’m always at some forefront of cultural discussion. Sometimes you just want to write a really good story to avoid those facts. In my next book, there will be no borders, no Mexicans whatsoever. It’s about World War II. What’s interesting about it, however, is that the border is a metaphor for what separates us. There are borders everywhere. My job as a writer is reaching over those walls that separate us to share a human story and to know the other stuff is peripheral. The important things are our families, our love for each other, and how we negotiate life and death and our legacy. That’s what I’m writing about.

Meet the Author

March 27

Warwick’s, 7812 Girard Avenue, La Jolla

PARTNER CONTENT

‘Literary Badass’ Luis Alberto Urrea on His New Cross-Cultural Book