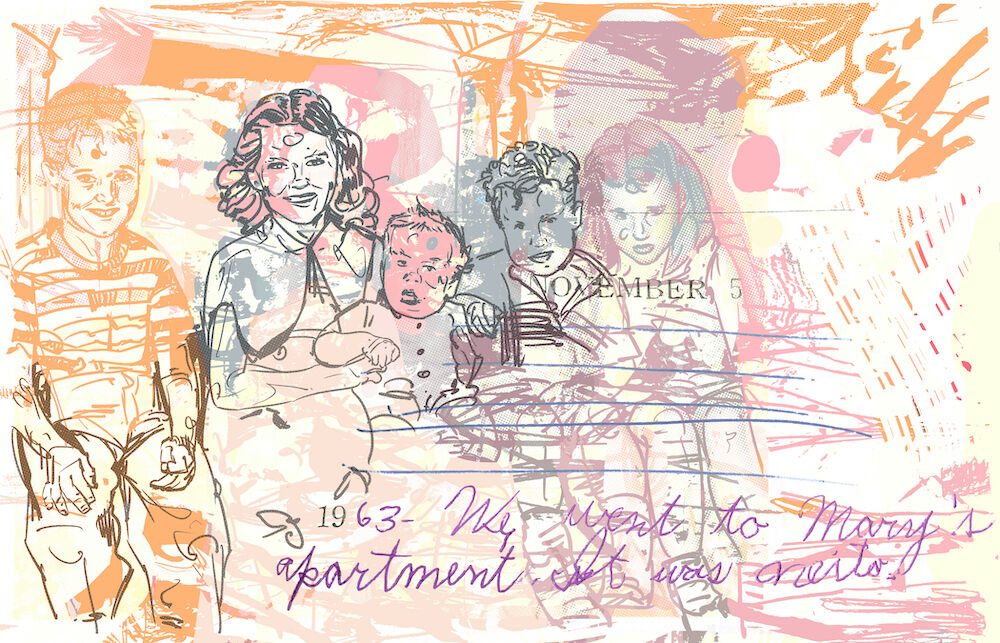

Reclaiming Mary – main illus

Jim Salvati

For 51 years, Rosalie Sanz told the same story about her sister, Mary. It goes something like this: When she was 23 years old, Mary was raped and strangled in her City Heights apartment. The person who did it broke into her home in the middle of the night. Chairs were knocked over, furniture overturned, objects smashed. Neighbors heard screams and crashes. No one called the police.

The conversation usually ended there. Occasionally, someone would follow up and ask if the police ever arrested anyone. Up until last October, the answer was always no.

On October 24, 2020, 75-year-old John Sipos was arrested on suspicion of the 1969 murder of Mary Scott based on DNA evidence and forensic genealogy. He pleaded not guilty that December. As of press time in September, the case is still in the initial stages of the court system, with a preliminary hearing scheduled for mid-September.

Search Mary’s name online and a lot of stories will come up: “Go-go girl found dead,” “Ex-sailor arrested in murder of go-go dancer,” “Navy veteran arrested for the rape and murder of San Diego go-go dancer.”

Most of these headlines aren’t from 1969; they’re recent. As so often happens to victims of violent crime, she was remembered only for what was done to her, and only in connection with the criminal. The final moments of her life eclipsed everything else about her. But Mary’s story, her real story, is not about her death, far less about her killer. It’s more about what came before, what came after, and how two loved ones she was forced to leave behind would persist for decades to seek justice and a chance to finally reclaim her memory.

Reclaiming Mary – family illustration

Illustration by Jim Salvati

One

“I always feel her with me, especially when I’m dancing,” says Rosalie. The carefree kind of dancing best saved for when you’re home alone or with a trusted group of friends. It reminds Rosalie of when she was younger, rifling through her family’s huge stack of 45s and dancing to them with her two older sisters, Nancy and Mary. Nancy would always claim she was the better dancer, so she took the lead in teaching Rosalie the Watusi, the mash, the twist. Sure, Rosalie remembers the moves, but mainly she remembers how Mary was never one to engage in her sister’s competitive repartee.

“Mary was the kindest and gentlest of us,” she says. “She was a very positive, very pleasant presence.”

That’s not time’s gentle touch softening her image of Mary. Every memory Rosalie has of her oldest sister is one that weaves a common thread of a quiet but commanding presence—the protector, the peacekeeper.

Growing up, Mary and her five younger siblings were divided into two rooms in their Clairemont home: the three boys in one and the three girls in the other. There in the girls’ bedroom, Mary taught Rosalie how to do cat-eye makeup and how to style her hair. She and Nancy would try on outfits for school

and for dances and let Rosalie play dress-up with their “twirly” skirts. Even when she was left to “lay down the law” when their parents were away, Mary always did so with a gentle hand. Once, when a nine-year-old Rosalie was caught smoking with her brothers, Mary lined each of them up and had them “swear to God” that they’d never smoke again. It would take nine years before Rosalie lit another.

Rosalie idolized her older sisters, always wanting to tag along with them when they’d head out around the neighborhood. Nancy would tell her to go home: “It wasn’t cool to have your baby sister tagging along,” Rosalie jokes—but she can still hear Mary’s voice as she’d smile and say, “Aw, let her come.”

Rosalie is 68 now. Both Mary and Nancy are gone. So are the boys. She’s had to live for all of them, in a way, but especially for Mary. Rosalie was only 16 when her sister was murdered; it left a chasm full of “what ifs” and “if onlys” that, over so many years, she’s had to learn to live with and let go of.

“For so long I only spoke of her death and felt her absence in my life,” she says. “It’s beyond time to start remembering her presence, too.”

Her presence is best felt in these snapshots, which make Rosalie’s memories of her sister spark to life. Memories of racing down the big hills and canyons surrounding Balboa Park, Rosalie strapped close to Mary on her bike, and of Mary starting family singalongs in the car ride home from church because she knew it made Rosalie happy.

As the girls got older, Mary would go off to dances and dates and recount everything to her two eager sisters when she returned home, climbing into the bottom bunk and lighting a cigarette as they asked her questions.

“I remember one time she had a date at Belmont Park and I was so excited to hear about it because I had never been before,” Rosalie says. Mary dished on every detail—what they did, what they ate, and what it was like to go on the big roller coaster. With her cigarette, she drew the track of The Giant Dipper through the air, up, down, and around again as smoke curled from her lips.

In 1963, Mary met Patrick Wyble, a shy Navy sailor from Opelousas, Louisiana, on a double date with friends. He picked her up in his car and the two hit it off instantly. Just a few months later, they were married at The Immaculata Church at University of San Diego during a week of Santa Ana winds. It was fast, but it felt right on time for Mary.

In the years that followed, they moved to Louisiana and had two daughters, Christine in 1964 and Donna in 1965. While there, Mary would write letters home about Cajun superstitions and crawdad catching and a horse named Grady.

“It all sounded so magical to me,” recalls Rosalie.

But truth be told, Mary was struggling. She and Patrick had hit a rough patch. They’d broken up and gotten back together a handful of times since they were wed; Mary would move back to San Diego with the girls, then return to Louisiana, only to come back again shortly after. In Louisiana, she missed her family and felt out of place. But back in San Diego, working and raising two girls as a single mother, with very little help for child care, felt nearly impossible.

In 1968, after one last attempt at making it work, Mary returned home without Patrick—and without the girls.

Rosalie was stunned. “She told me she didn’t have the heart to take the girls away from their family there. Mary felt that was where they needed to be because she couldn’t be the mom she wanted to be. Of course, I was heartbroken and judgmental. I didn’t empathize or understand. I have a lot of regrets about that.”

Now on her own, Mary got an apartment and started working as a cocktail waitress and then as a go-go dancer, first at the Concord downtown with Nancy; then at the Star & Garter in North Park. Both of them loved to dance. Beyond their childhood dancing around the house, the girls had spent most of their teen years at the YMCA downtown attending USO dances. It felt like a natural move for Mary to start dancing at the club, and an easy way to make money doing something she loved. And she seemed grateful for it all, always smiling and upbeat at work. Her coworkers swiftly nicknamed her “Lucky” because she was always so “happy-go-lucky” when they saw her.

“I just feel lucky,” she’d tell them. “Lucky to work here, and have a job—just lucky.”

Two

It was around 10 at night when the doorbell rang. November 20, 1969. From her room upstairs, Rosalie peered out the window and saw two men in suits standing outside. “It was odd; I knew something was not right,” she remembers. By the time she went downstairs, her parents had already closed the front door.

“I knew it had to be something horrible, so I kept asking, ‘What’s going on? What’s going on?’ My mom just turned to me and said very plainly, ‘Your sister’s been raped and strangled.’ Then she went into her bedroom and shut the door.”

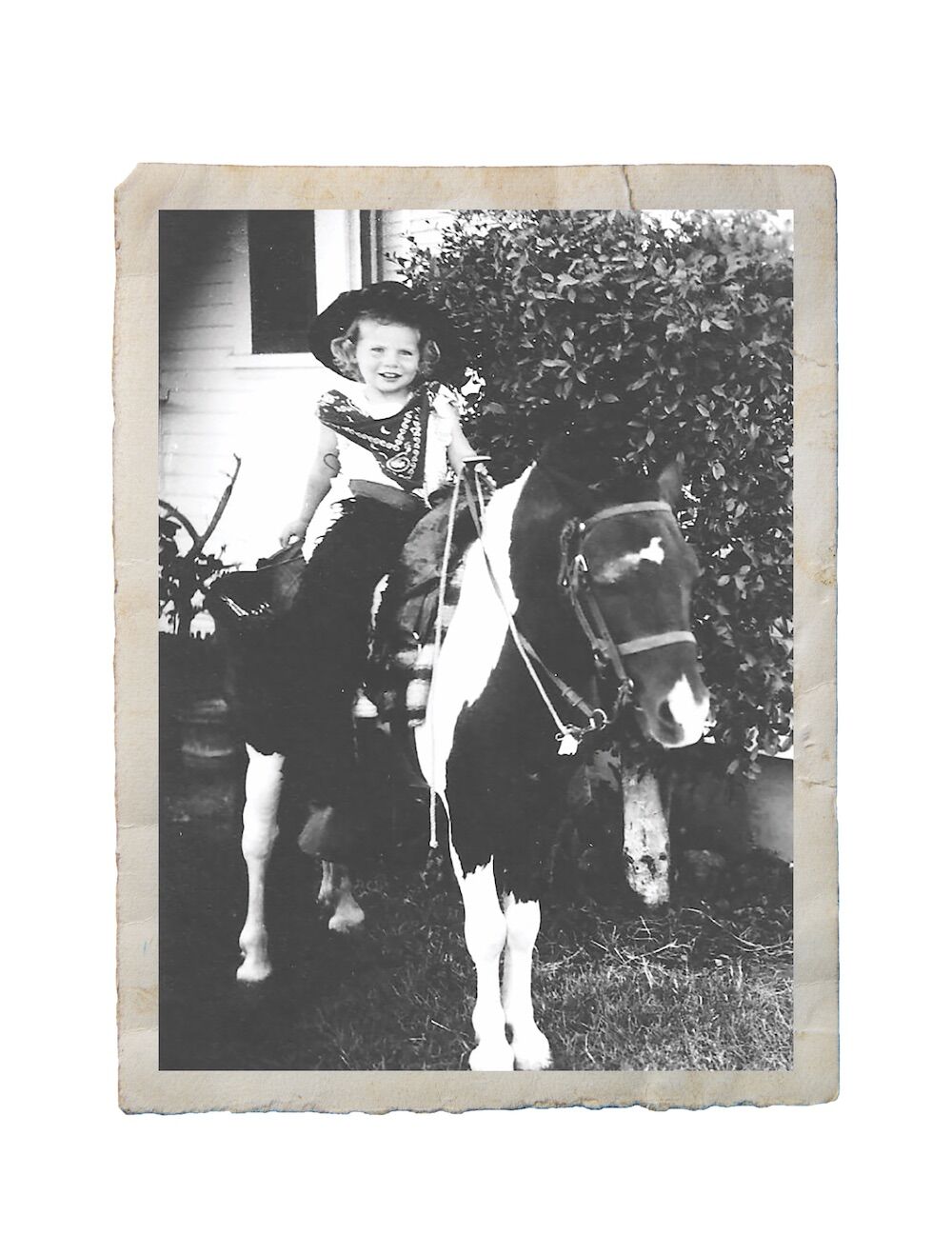

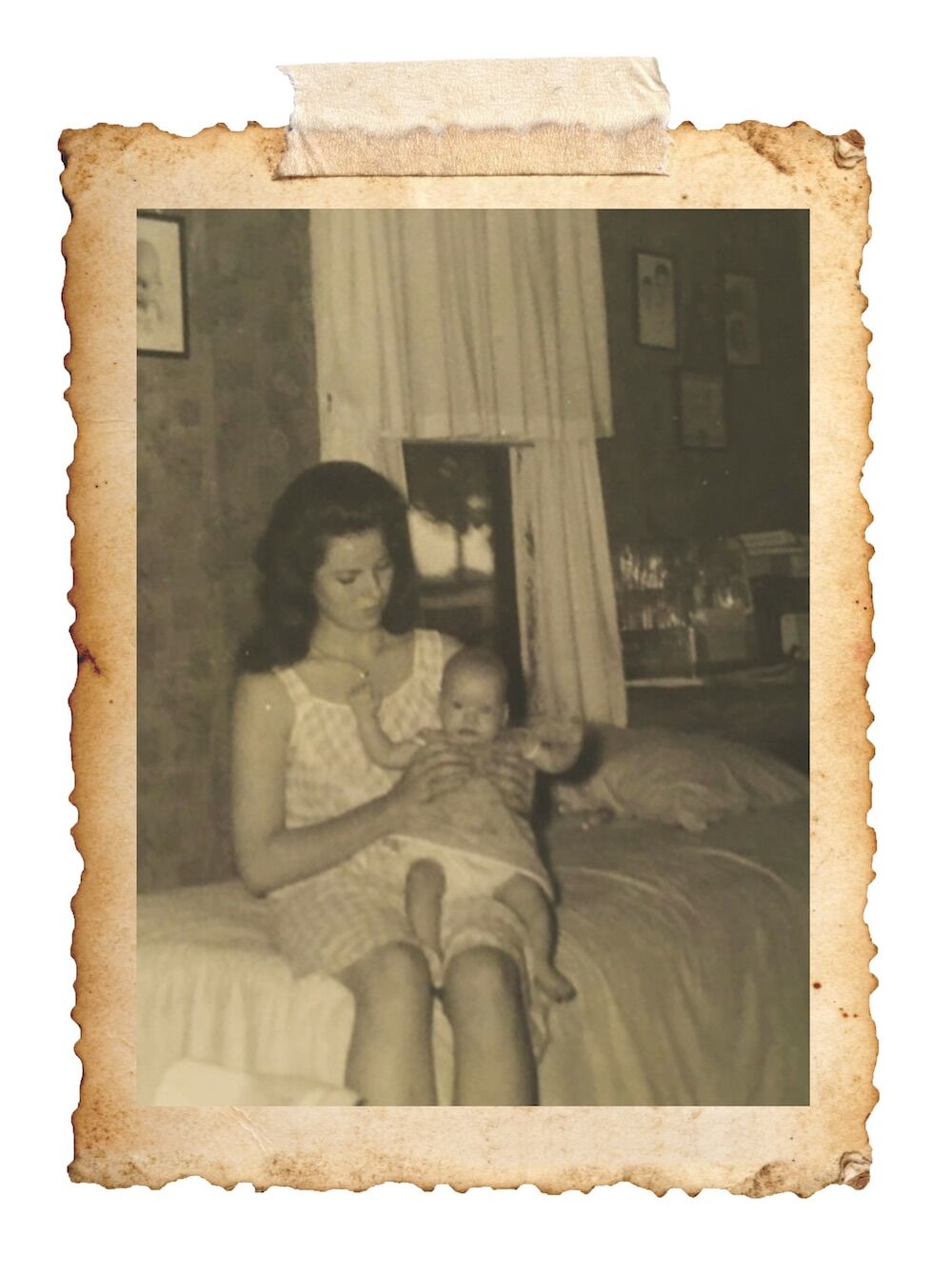

Mary as a toddler in San Diego

Mary was murdered that morning at about 2 a.m., Rosalie says, shortly after returning home from work. She’d had plans with her best friend and coworker to meet at the club later that day, so Mary could help her get ready for a date. When Mary didn’t show, her friend asked her date to take her by the apartment. It wasn’t like Mary to not show up, and it was a quick stop on their way to dinner—the apartment was just a few blocks from the club. As she neared the door, she heard the television going and joked to her date about that being what had held Mary up. When they walked in, they found the apartment a wreck. The chain on the door was broken, the chairs and furniture flipped. Then she saw Mary on the living room floor—her nightgown ripped off, her jaw broken, and her body still.

“After my mom told me what had happened, I remember going into my room and punching my pillow and just screaming,” says Rosalie. “The thing that struck me the most was that it was so unfair, because she had her whole life ahead of her. She could have done anything. She could have been reunited with her kids. She could have made her dreams come true, and it was just over? Time’s up? It just wasn’t fair.”

The news traveled across the country in a yellow telegram. Donna and Christine, then five and six years old, were sitting on the front steps of their grandparents’ trailer in Louisiana, watching as their grandmother carried that piece of paper across the field toward them.

“All of a sudden she was crying, and we were so young, we really didn’t know what was going on,” says Donna, who’s now 56 years old. “It had been a while since we’d seen her, so we really couldn’t comprehend what was happening. We didn’t question it.”

Mary’s case went cold fast.

The crime scene was processed, evidence was taken, and immediate leads were exhausted. Reports of her murder stayed in the news cycle for only a few days, says Rosalie, and they focused more on her job as a dancer than anything else. That’s still one of the things that bothers Rosalie most, 52 years later—how quickly Mary was reduced to nothing more than her profession.

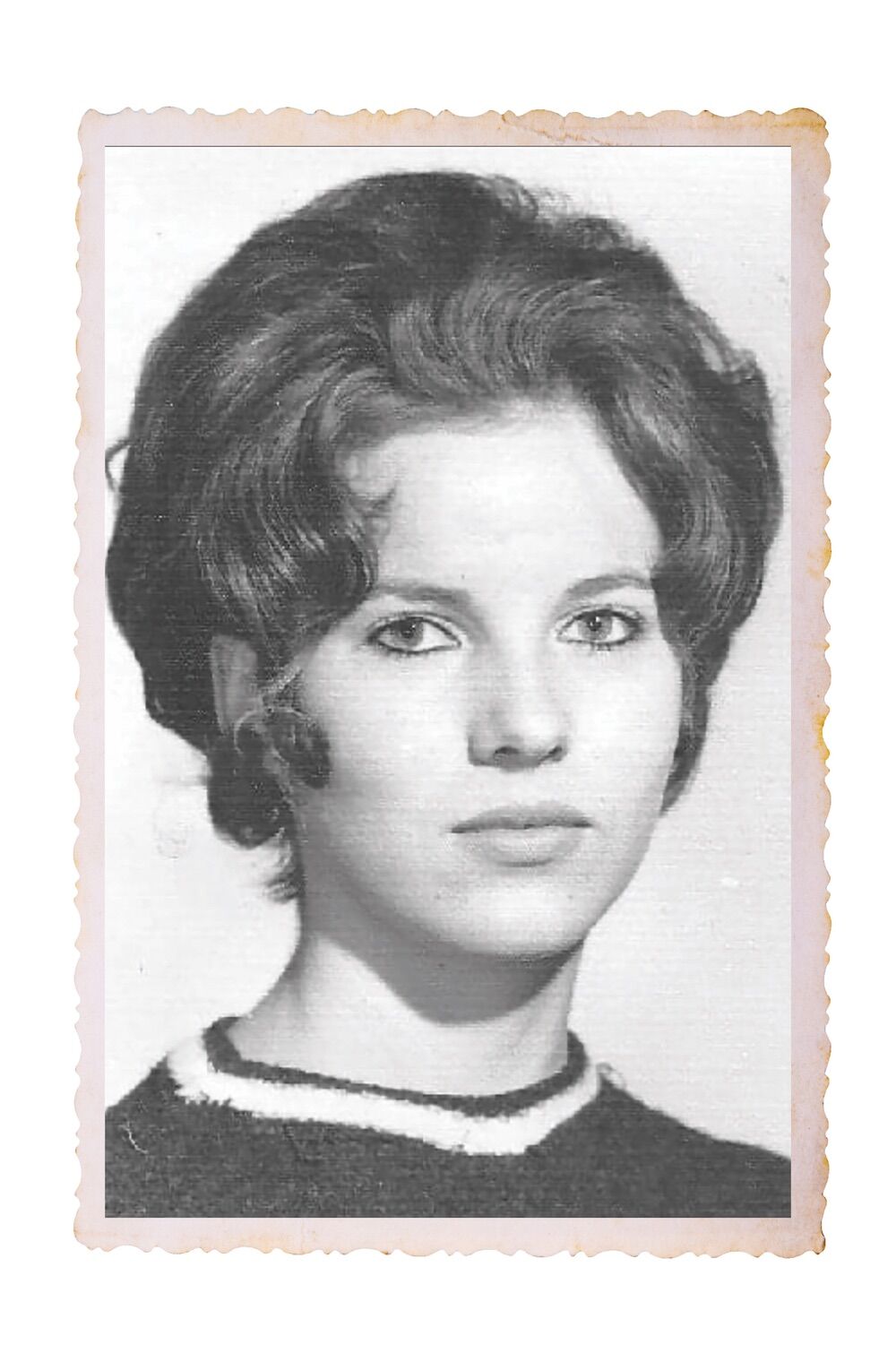

A yearbook photo of Mary from Madison High School in Clairemont

It’s a familiar phenomenon. One that Joni Johnston has seen for more than thirty years as a forensic and clinical psychologist. She’s worked at a medium-maximum security prison, for California’s Board of Parole, and for the Superior Court of San Diego to understand the psychology behind why people commit the crimes they do, and, in the case of sex crimes, why it’s so common for the victim to be blamed.

“With a headline like ‘Go-go girl found dead,’ the implications are clear,” Johnston says. “There’s this unspoken attitude that if this person hadn’t been doing this thing, then they wouldn’t have gotten killed. When, of course, the reality is that there’s no link between her profession and the crime.”

It may be easiest to pin this bias on the media itself, but Johnston says the public is just as responsible.

“Obviously the media can influence public perception, but I think the media reflects public opinion just as much,” she says.

It’s a knee-jerk way of reassuring yourself that you’re still safe. “It’s this logic of ‘if I can psychologically distance myself from the victim, it’s never going to happen to me.’”

And it’s part of the reason why only one in six rape victims report their attack, she says. They’ve seen how they might be characterized in the media and decide not to come forward. Their attackers suffer no consequences, believe they can get away with it again, and the cycle continues.

This culture of victim blaming can also have an effect on how these cases are handled, Johnston adds. Generally, when law enforcement believes that the victim works in a high-risk occupation, they may be apt to assume the case will be too difficult to solve and will approach it with less scrutiny.

Rosalie watched as all of these factors seemed to crush her parents. They refused to talk to the press, she says, noting that they felt embarrassed by the way Mary was being portrayed. In those early days after the murder, they wouldn’t even speak to the police—when a detective looked at the case file in the ’90s, he found no notes or quotes from anyone in the family at all.

“No one in my family was really interested in finding out who did it—what we cared about was that she was gone and wasn’t coming back,” Rosalie says. “Life just had to carry on somehow.”

So the case went cold. Donna and Christine stayed in Louisiana to be raised by their grandparents. And back at home, Mary’s photos were taken off the walls.

“Just like that, there were no pictures of her anywhere,” Rosalie says. She went back to school three days later. Most of her friends didn’t even know it had happened, and the few who did didn’t know what to say. “It was a very isolating feeling.”

At home, her parents didn’t want to talk about it and her other siblings didn’t push. But Rosalie just couldn’t leave the photos alone. One day she snuck into her parents’ bedroom

in search of them and found them shoved into the top drawer of her father’s nightstand. “I just confronted him about it right then,” she says. “I wanted them on display so we could remember her and talk about her.” Her father said nothing, and the next time Rosalie poked around in the drawer, the photos were gone completely.

“I have very few pictures of her left.”

15-year-old Mary at her neighbor’s house

Three

Donna has only one memory of her mother. It’s Christmastime, and she and her sister Christine are surrounded by toys in their mother’s small apartment in San Diego. Against a wall, Mary had drawn and cut out a pretend fireplace made of cardboard. “For Santa to come down the chimney,” says Donna. “That’s all I remember.”

Her father’s parents raised her and her sister for most of their lives, since Patrick worked on an oil rig and was often out at sea. Growing up, they referred to their grandmother as “Mama,” and essentially had no concept of their mother or their family in California.

“She wasn’t talked about,” Donna says. “My dad was gone a lot and I think it was painful for him to talk about her; and my grandma, I think, had a fear that if we found out and went to California, we wouldn’t come back.”

As the girls grew, their curiosity got the better of them. And just as Rosalie had snuck into her parents’ bedroom to search for Mary’s photos, years later Donna and Christine would sneak into their grandmother’s room and find a hope chest full of Mary’s belongings. Her wedding dress, her veil, her death certificate—all neatly placed inside.

“My grandma was furious when she caught us,” Donna says. “But even then, she didn’t explain how she died. She finally just told us that we had a mother from California who had passed away.”

It would be years before the girls pressed the matter further, and even when they did, it was in secret. Christine hired a private detective in 1988 to find anyone related to Mary; at the time, not even Donna wanted to be involved.

“My grandmother had told us not to fool with it and I listened to her,” she says. “She tried to protect us, in her own way, because of what happened to my mom. There was this idea that if we went, maybe what happened to my mom would happen to us. So I wanted nothing to do with it.”

But Christine felt differently. When the private detective finally tracked down Rosalie, Christine called her out of the blue and opened up about the years she’d spent wondering about and longing for her family in California.

“She told me that she wanted to meet the family that looked like her,” Rosalie says, and laughs. While Donna, her father, and her grandparents all had the same dark hair and brown eyes, Donna says that Christine was the spitting image of Mary. The same strawberry blonde hair, the same green eyes, and the same sweet—at times naive—disposition.

“My sister loved to dance and loved music,” Donna says. “She never saw anything bad in anyone; she never judged anyone. She was a good person with an innocence about her. That’s how Mary was, too.”

Christine and Rosalie exchanged letters for months, writing about Mary and what she was like, but also writing about their own lives and families. Christine was married and had two kids; Rosalie was in her 30s and living in San Diego with a family of her own. They planned for Christine to fly out so they could meet in person someday. But that day would never come.

Late at night on December 20, 1989, Christine was driving home from work. The road was icy. Donna says they still don’t know whether she fell asleep at the wheel or lost control, but the state trooper who arrived at the scene would tell her grandparents that the car flipped six times, breaking both of her legs and her neck. She died instantly.

“It was just so similar to what my mom went through. They both left behind two kids, they both died around the same age. It just felt like a curse repeating itself.”

Time stood still for Donna. Once the initial shock wore off, the weight of losing her sister slowly crept in and made a home for the next few years. But by 1992, a new resolve came over her. “That’s when I decided that I would finish what Christine started,” she says.

A year later, she was on a plane to meet Rosalie in San Diego.

They headed to Old Town as soon as she landed and drank giant margaritas. She brought one of Christine’s sons with her and they all stayed at Rosalie’s home. Donna made gumbo, one of Rosalie’s daughters helped peel the garlic, and Christine’s son recorded the gathering on video.

It was around that time Donna and Rosalie first discussed wanting someone to reopen Mary’s case. That planted a seed that would eventually lead them to a cold case detective from the San Diego County District Attorney’s office named Ron Thill in 1998.

He connected with Rosalie in Sacramento, where she had moved a few years earlier, to go over the case. Back then, the US didn’t have a national database of DNA to compare samples from crime scenes against. You could only directly compare DNA evidence against individual suspects—and that’s assuming you could get ahold of them, or their DNA was already on file in a state or local database. So they could exclude the handful of suspects the police had, including Mary’s ex-boyfriend and the boyfriend she had at the time of her death. They were both cleared, and after that, nothing but more dead ends.

“That was really disappointing,” says Rosalie. “On one hand it was good to know that it wasn’t anyone we knew. But it was still sad that it just came to an end again.”

Mary’s daughter, Christine, in between Mary’s parents, John and Dorothy Scott, in Clairemont

As she’d done before, Rosalie picked up the pieces and life carried on. She moved around Northern California with her family, got divorced and remarried, and by 2019 had settled back into Sacramento.

The year before, Joseph James DeAngelo, known as the Golden State Killer, had made headlines when he was arrested for 13 murders, 50 rapes, and 120 burglaries he committed across California during the ’70s and ’80s. It was the first widely publicized case to make an arrest using DNA that’d been uploaded to a genealogy site, and it got Rosalie thinking.

“I reached out to a friend of mine who was a retired cop and said, ‘You know, I keep reading about all these crimes from decades ago that are being solved through ancestral or forensic genealogy,” she says. She asked why they couldn’t do the same for her sister’s case. “He said, ‘Well, we probably can.’”

Four

Five months later, someone came knocking.

It was April 23, 2020 and, like most days at the beginning of the pandemic, a pretty quiet day at home for Rosalie. “I can’t even tell you what the weather was like,” she laughs.

Mary at her First Holy Communion

At the door was a Sacramento cop with a message for her to call the San Diego District Attorney’s office. When she called, she found out they were planning to use the DNA taken from Mary’s crime scene to do a forensic genealogy run and see if there was a hit.

In early September, they found a match in Pennsylvania.

“I couldn’t believe it,” says Rosalie. “I was so happy that they found him and that he was alive.”

But they couldn’t go after him just yet. The San Diego Police Department and the district attorney’s office had to secure an arrest and an extradition which, she was told, could take months.

“That was the worst part,” Donna says. “The waiting game. I’m just thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, go get him, what are you waiting for?’ But let me tell you, there are so many legalities when it comes to DNA and especially when it comes to cold cases. You bet all your t’s are crossed and your i’s dotted, because with any minor drop of the ball, the whole thing can be thrown out.”

According to Justin Brooks, a criminal defense attorney and the director and cofounder of the California Innocence Project, using genealogy sites to help solve cold cases is the new way forward for detectives and attorneys.

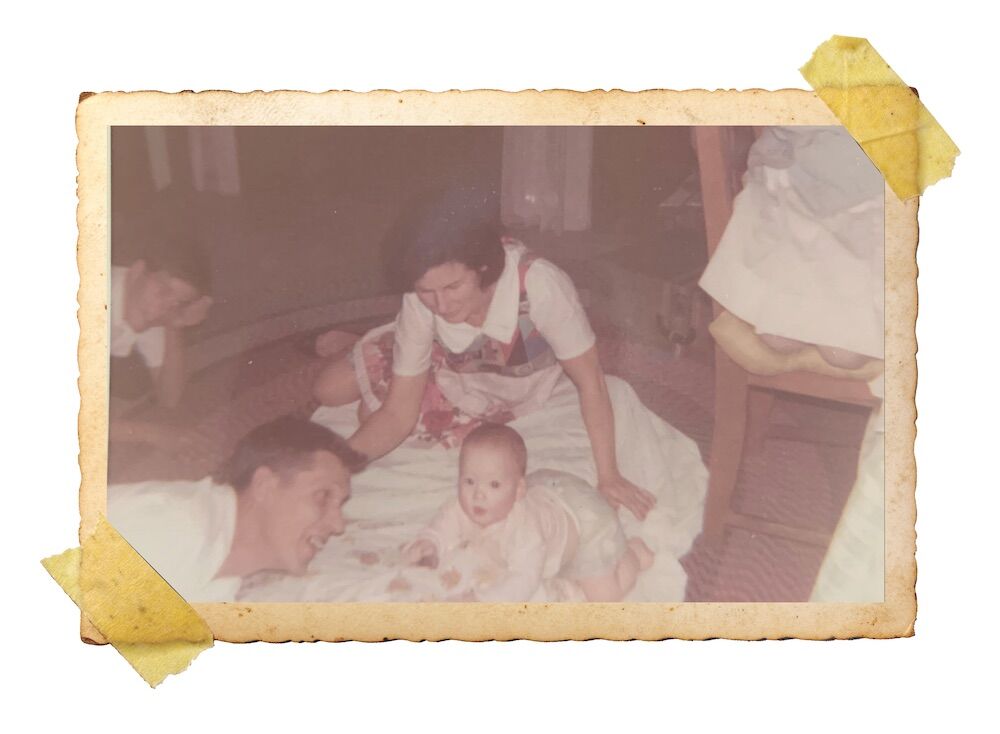

Mary with baby Christine in her apartment

“DNA has made it possible to do stuff I couldn’t dream of doing,” Brooks says, noting that even the development of mitochondrial DNA testing a decade ago significantly changed the game by creating a way to test hair without its roots. “It was huge. We were able to go back and look at old cases where we had hair samples without the roots and match it up.”

Now he believes it’s only a matter of time before there’s a global DNA databank that everyone’s a part of. “That’s a long way away, but it’s a pretty interesting evolution that people who would normally not want their DNA in a databank are putting it out there onto genealogy sites because they think it’d be cool to find out more about their ethnic background.”

In Mary’s case, this advancement changed everything. Rosalie credits the San Diego Police Department and the San Diego District Attorney’s cold case unit for never closing her sister’s case. “When the DA investigator told me they got a hit using forensic genealogy,

I knew we had found the killer,” she says. “Learning he had lived in San Diego at the time just added to my confidence that this is the guy. I’m looking forward to hearing more evidence at the upcoming preliminary hearing.”

Donna notes that it’s worthwhile for any family grappling with a cold case to push for forensic genealogy testing.

“It’s not going to bring your loved one back and it’s not going to heal that pain,” she says. “But it may lead you to the person who did it, and that’s worth everything.”

It’s still unproven whether or not John Sipos is that person. He waived his right to an extradition hearing and was taken into custody from Pennsylvania willingly. At the arraignment in San Diego on December 22, 2020, Sipos pleaded not guilty.

The status hearings and preliminary hearings that were scheduled for earlier this spring were all postponed. Brooks says that can happen for a number of reasons—either the attorneys came to an agreement to postpone or, more simply, the court system is still extremely backed up from the pandemic and the case is just one of many awaiting its day in court.

Mary in her wedding dress in 1963

What comes next remains to be seen. For Rosalie, the biggest hurdles have already been crossed. Now it’s just a waiting game to see whether a lifetime’s worth of uncertainty might find peace.

“Fifty-two years were taken from her. Who knows what she could have done or who she could have been. My whole family’s life changed at that time. It changed everything. If he is the person who did it, it is just that he would spend the rest of his life in prison.”

For Donna, the road to closure, whatever that looks like, will be a long one. “When people tell me that I finally have closure, it’s not like that.” The arrest alone hasn’t produced that feeling. “I’m still learning so many things about my mom and family. In many ways I feel like all of this is just beginning for me,” she says.

Five

The pain never really goes away, Rosalie says. But for as much as she lost when Mary was murdered, she gained some things, too.

“The often-used expression ‘life is short’ came to have an actionable meaning to me,” she says, noting that she now actively appreciates every moment she has with her husband, her children, and her eight grandchildren in a way that most people who haven’t experienced a tragedy like hers can’t comprehend

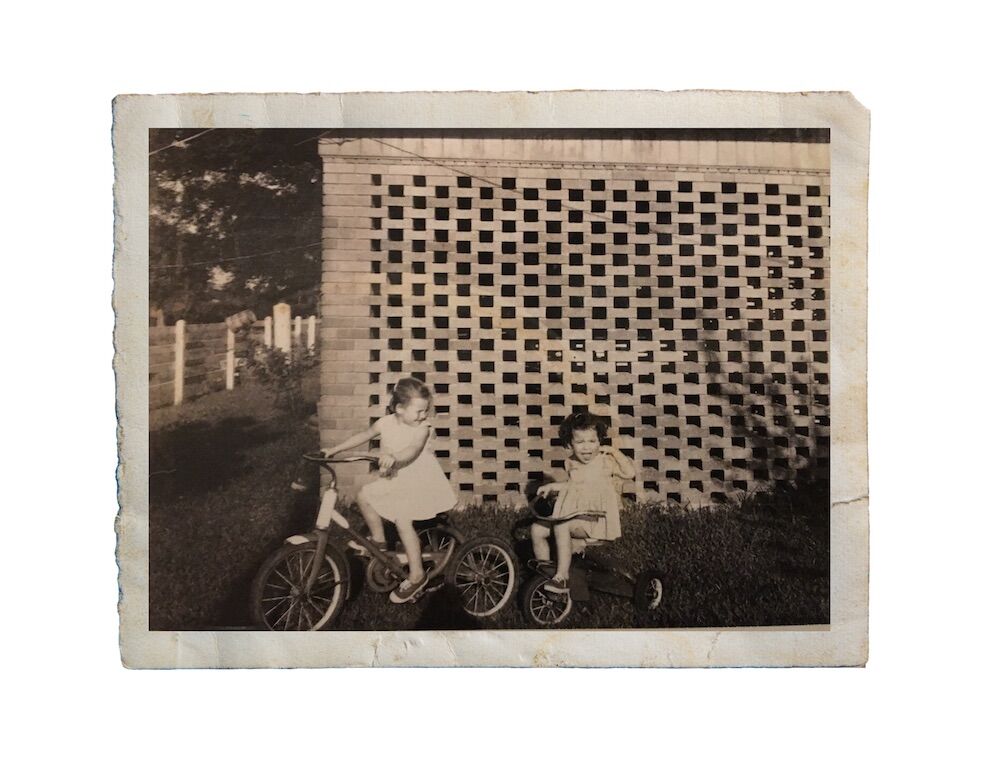

Christine and Donna riding bikes in Louisiana

At the time of Mary’s death, Rosalie had distanced herself from her sister quite a bit. The guilt that followed after was enough to shake her awake and change her perception, especially about her relationship with her other sister, Nancy.

“I intentionally spent more time with Nancy,” she says. “I visited her often, I helped her out when she needed it. When I lost her just three and a half years after Mary’s death, of course it had a huge impact on me, but I didn’t have the same regret of time wasted.”

She also gained her niece back. Donna still lives in Louisiana, close to her daughter and her grandchildren (“Mary has great- grandchildren now, isn’t that beautiful?” Donna adds), but she keeps in touch with Rosalie in regards to the case and the major happenings of their lives. Enough time has been lost between them—it’s about looking forward now.

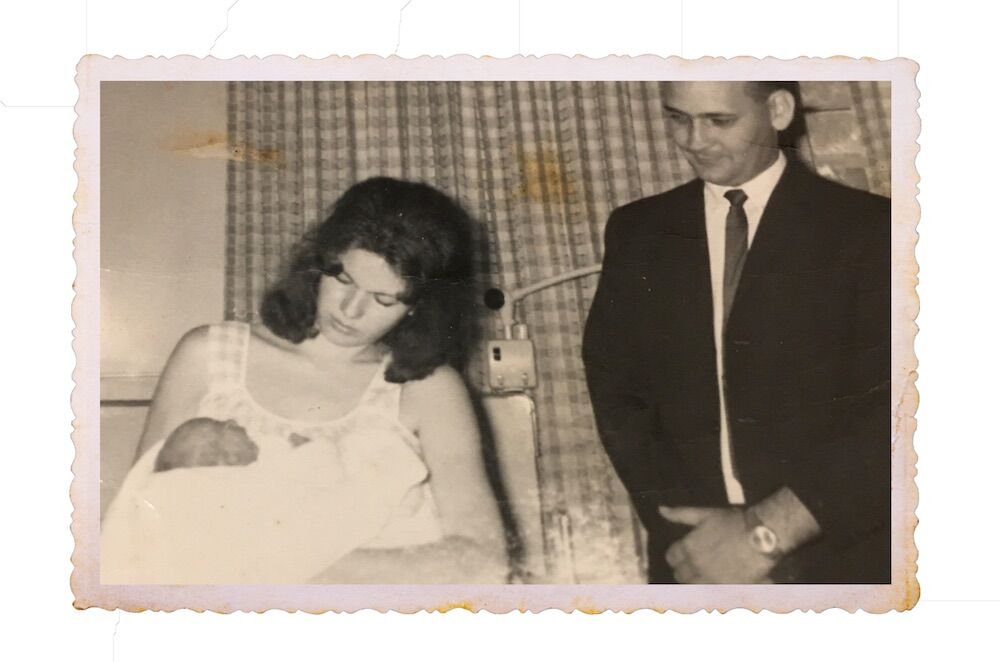

Mary at the hospital with newborn Christine in 1964

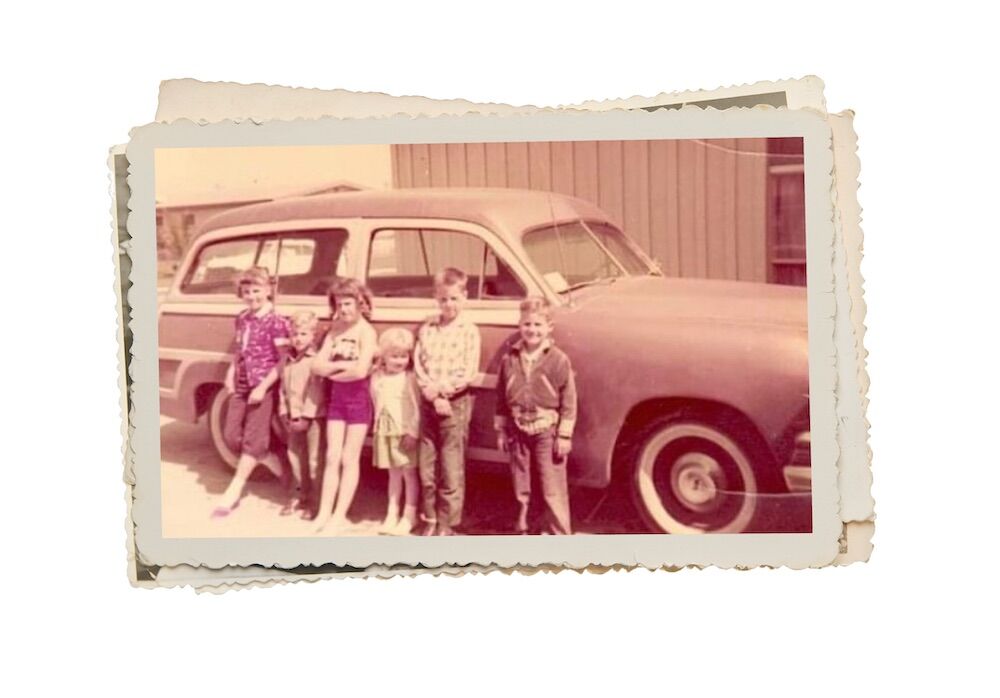

Mary with her siblings, David, Nancy, Rosalie, John, and Bill, in 1956

It’s a foreign feeling for them. After 52 years of looking only to the past, it’s hard to comprehend that the future may bring resolution. The idea of justice for Mary feels twofold: There’s the justice they’re still waiting to see play out in court. Then there’s the kind they feel they’ve already won. A kind that’s much more personal; in which the narrative of Mary Scott is no longer shrunk down to a tawdry headline, but drawn wide open and reclaimed by two of the people she loved most.

“I hope to do my sister, and the memory of her, justice. Not only for her, but for me, and my siblings, and my parents,” says Rosalie. “I loved her so much. I still love her so much.”

***

PARTNER CONTENT

After a two-day preliminary hearing in September, San Diego Superior Court Judge Jay Bloom ordered John Sipos, who was arrested last year on suspicion of murdering Mary Scott, to stand trial. Over the course of the hearing, Deputy District Attorney Chris Lindberg presented 12 witnesses to testify to prove to the court that there was enough evidence for Sipos to face a trial. Those witnesses included DNA analysts, officers who first responded to the scene, the cab driver who drove Scott home the day she was murdered, and Scott’s friend who found her body. A trial is set to start in January 2022.