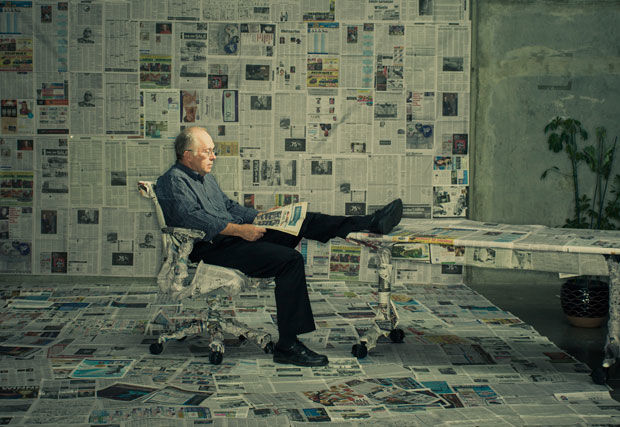

Kent Davy

Kent Davy served as editor of the North County Times for 16 of its 17 years. | Photo by Robert Benson

In October 2012, Doug Manchester, owner of U-T San Diego, bought out his biggest local rival, the North County Times, but it wasn’t until May that Manchester and U-T San Diego CEO John Lynch swept away the last vestiges of the northern paper when they shuttered its North County edition, laid off all the journalists at The Californian, and let go a dozen or more former NCT staffers. The move ended an 17-year run that began when Howard Publications merged the North County Blade-Citizen, the Escondido Times-Advocate, and The Californian in 1995. At its peak, the paper employed roughly 500 people. It covered three major wildfires, high school sports, local politics, and the 2001 power crisis, and even sent a team to Iraq three times. This is the tale of that paper, as told in the words of its staff to Eric Wolff, himself a reporter for the paper between 2009 and 2012.

DICK HIGH (Publisher, 1995–2007): The situation (in 1995) was, you had a problem: All three papers [the North County Blade-Citizen, the Escondido Times-Advocate, and The Californian] were seeing either a slow or rapid decline in profitability. Put them together and you had a negative 40 percent profit margin—and in decline. We set out with a very clear growth strategy: I’m going to put a lot more money into the things that other papers would be tight on. The result was that this thing turned around.

BRADLEY FIKES (Reporter, 1997-2000, 2001-2012): The joke was people at the Blade-Citizen, they were the party-hearty types; the people at the Times-Advocate would have little teas and be eating their cookies.

KENDT DAVY (Editor, 1996–2012): There were two managing editors, Rich Petersen and Rusty Harris, at the Times-Advocate and the Blade. Rich became the first editor of the North County Times, and Rusty was managing editor. They had a crisis in the business office, couldn’t get the bills out, they were losing money. I remember standing in the newsroom in Munster, Indiana, saying, “Oh man, the Howards are going to close that thing down because the Howards are losing so much money.”

HIGH: The Howards were very tough. I remember, month after month, they would send me a check for a million dollars or more.

North County Times staff in 2012

The staff of the North County Times, outside the Escondido headquarters in September 2012.

High organized the North County Times circulation area into nine “zones,” meaning nine regions whose readers received unique front page and local pages based on their local news.

HIGH: We decided we would start zoning and sell a lot of little ads, sell a lot of the smaller mom-and-pop stores. If you look at the North County Times, we were full of a lot of little ads as well as big ads. If you have all big ads, it’s like monoculture. That’s okay, but it gets boring pretty fast. The ads themselves have readership value.

DAVY: One of Dick’s innovations was a letters page that was completely wide open. We were going to print every letter from the community and about the community, and as quickly as possible. This provided a forum for people to have debates there. When you got to election season, we ran four or five pages of letters to the editor in a given day.

—Dick High, Publisher, 1995–2007

RUSTY HARRIS (Managing Editor, 1995–2010): We had this huge fire break out in western Escondido (the Harmony Grove Fire in 1996). Of course, the inland staff, from the old inland paper [the Escondido Times-Advocate], said, “Aha, this is our story.” The problem was, the fire was pushed by the wind so hard and so fast it became a bigger story in the coastal zones, which means the focus shifted to the old coastal paper, and then its staff covered the story. As hellish as it was and as heartbreaking as it was, it kind of tied the two staffs together.

In 1996, Rich Petersen left the paper for the Union-Tribune. High hired Kent Davy, then managing editor of the Times of Northwest Indiana.

DAVY: Newspapers that bind themselves or build a relationship to the community become mirrors, a mirror to the community itself. You do that by, first off, honoring what the community cares about. In trying to think about our role, we would say to our staff, we are North County-centric almost to the point of being parochial about it.

JAY PARIS (Sports Writer, 1995–2012): Friday nights were a complete fire drill. We were so local, we wanted to cover every high school and get names in the paper. Where a lot of papers maybe have a line score, we tried to be at every high school game.

CYNDY SULLIVAN (Photographer, Photo Editor, 1995–2007): I got a letter from a little girl. I had published a very candid photo of her, this little girl picking yellow flowers. She sent me a note saying she was famous now and people at her school were asking her for autographs. Maybe a month later, there was a horrific accident involving some Marines on a remote stretch of Winchester Road between Temecula and Hemet. They’re notoriously strict on access when it comes to anything involving the military. There was a very large police presence at the accident. I was not getting much cooperation, so I introduced myself to a police officer as Cyndy Sullivan with the Californian. The officer said, “Cyndy Sullivan? With the Californian?” I thought he was going to tell me to get out of there. He said, “We love you! Our family loves you! You took a picture of our daughter in the flower fields. We just love you, we have your picture on the refrigerator!” He told me he would help me in any way he could to gain access to this military situation.

In 1997, 38 members of the Heavens Gate cult committed suicide in Rancho Santa Fe.

JAMIE LYTLE (Photographer, 1995–2012): I came walking up with Timothy O’Hara, a reporter; we were way out in Rancho Santa Fe. He said, “There’s 38 dead people up in that house right there.” We were the only two guys there, there was one cop standing in front of the house. Four hours later, the whole world was there.

HAYNE PALMOUR IV (Photographer, 1995–2012): I remember flying in the helicopter above it. Kent sent me up there. We were just watching wrapped-in-white-sheet body after body after body coming out the door of that mansion and into a truck—the medical examiner’s truck. It went on forever.

In 2003, the North County Times sent reporter Darrin Mortenson and photographer Hayne Palmour IV to Iraq, the first of three trips the pair would make.

HIGH: My view was, North County went to war. That’s all there was to it. Forty percent of all the fighting over there was done by guys stationed in North County.

PALMOUR: [The newsroom staff] presented us with this cake and it had little plastic Army men on top of the cake. I do remember thinking, “How nice, a cake. A cake with Army men. Thank God it doesn’t have red icing pouring out.”

Palmour and Mortenson were embedded with a Marine battalion.

PALMOUR: We had a satellite modem we had gotten to work. We knew how to work it, but it was really hard, you had so many media trying to connect to it in that country. I had shot a ton, and Darren had a ton of stories, but by the time we stopped and put out the satellite gear, a massive sandstorm hit and we couldn’t do it. Five days passed before we could finally connect to the satellite. We kept envisioning that they were getting mad back in that newsroom. We found out when we came back that Kent didn’t even sleep at night.

DAVY: There’s a real helpless feeling when you are half a world away.

PALMOUR: There were a pair of Reuters photographers in the same battalion. They had a better satellite setup. I asked them, “Can you please let me send an email to my newsroom?” By the time I sent that email I’d seen a lot of death. I wrote, “We can’t connect to satellite, we’re getting error messages. Please tell our parents that we’re okay.” The Reuters photographer came back, “I got lots of replies to your email.” It was just this outpouring; we were so relieved. They thought we might have been killed.

In October 2003, the Cedar Fire swept through North County, burning 280,278 acres and killing 15 people.

PALMOUR: I was heading toward Scripps Ranch and I could see this gigantic brown cloud. This was a monster. This was a big dangerous monster and I just got into it, and next thing I got on a street and all the houses were burned down or still burning.

In 2002, Lee Enterprises purchased Howard Publications, and with it the North County Times, for $694 million. In 2005, the corporation bought Pulitzer Inc., for $1.5 billion.

HIGH: Lee is a good newspaper group, but they’re a corporation. They bought the Howard papers and it worked so well, they decided to do it again, so they decided to buy the Pulitzer papers. That time they went deeply into debt to do it. They paid a high price and then the Great Recession occurred. They got hung out to dry and pretty soon the company was basically de facto being run by the creditors. Wall Street creamed ’em.

breaking up furniture in the old North County Times office

After the sale became official on October 1, 2012, workers employed by the U-T San Diego came in during the work day and broke up the furniture and carted it off. This shot faces the former locations of cubicles occupied by (from left to right) features editor Laura Groch, managing editor (now U-T business columnist) Dan McSwain, and editor Kent Davy.

In October 2007, the Witch Creek-Guejito fire and Rice Canyon fires killed two people and burned 197,990 acres in North County. The Rice fire burned 9,700 acres in Fallbrook.

DAVY: [Assistant editor for new media] Michael Donnelly was up all night on the website when we opened comments up and got thousands and thousands of comments. He engaged in conversation in Fallbrook and De Luz, which weren’t getting a huge amount of coverage. For a week or so, our comments section turned into this great conversation. People talked to us and as a community tried to sort out what was happening.

—Peter York, Publisher, 2007–2012

In Between 2007 and 2009, housing prices plummeted and foreclosures skyrocketed. The economy shook up the county and the paper.

ZACK FOX (Housing Reporter, 2007–2009): We could walk up and down the street and knock on people’s doors who’d had foreclosure notices. I could have a story on every other block. Nobody really knew what was going on. We came up with the idea of having a forum where we would discuss the state of the market. The response was completely ridiculous; we packed the [Escondido] library auditorium.

PETER YORK (Publisher, 2007–2012): It was a bell curve turned upside-down of newspaper revenues, starting in 2007 and bottoming out in 2012. We got down to three zones, we closed an office in Vista, we closed an office in San Marcos. We really got pretty lean and mean. We were still in the black.

DAVY: In the first 10 years or so of the North County Times, the shrinkage of the staff was all done by attrition. In 2007 we started seeing the signs. In 2008 it really accelerated; we started going through spasms of layoffs. It was the summer of 2008, I guess, in which 25 people were laid off. Those things were gut-wrenching for me. Most people took it with more grace and more courage than I would have expected. One guy left and was so angry. The publisher was driving out of the parking lot, [and] he slammed his fist into the hood of the publisher’s car.

In February 2009, 14-year-old Escondido resident Amber Dubois went missing. Her killer, John Albert Gardner III, confessed a year later to kidnapping and killing her along with 17-year-old Chelsea King.

North County Times newspapers

North County Times newspapers.

CHRIS NICHOLS (Reporter, 2008–2012): It just so happens that I lived up the street from the Dubois family, about three or four blocks away. It was a very emotional time for the community. [Six months after the abduction], I went up to Amber’s room with her mother to go through all of her personal items and I watched her cry. That was one of the more difficult ones: Watching her mother cry, looking at all of Amber’s possessions, her posters, a Twilight poster on her wall, a sketchpad where she would draw wolves. It was a deeply personal experience—a direct window into their world and their pain.

YORK: (In early summer, 2012), myself, the finance director, Tim Bruinsma, and Peggy Chapman were told to meet our operating vice president [from Lee, in Iowa] over at the Carlsbad Airport. He and the VP of human resources flew in and said, “Hey, you guys have been sold.” That was the first time I heard. It was a shock to us as a management team.

NICHOLS: We all knew the North County Times’ parent company had financial troubles. Some of us were surprised, and maybe disappointed, that we were being purchased and the North County Times would go away.

HIGH: Wall Street took away North County’s newspaper and the execution was at the hand of Manchester.

YORK: Not a day goes by that someone doesn’t say [to me], “I hate the U-T, I wish the North County Times was back. I can’t get anything in the paper. They ignore us.”

DAVY: The sale of the newspaper was pretty stunning. I had bought the company line that they saw great value in us and would ride it up, just as they rode it down. So, when I was told of the sale, I was hit by a hammer. The worst part was living with the knowledge that the end was coming but being under orders to keep my mouth closed. There were only a handful of top NCT execs that knew in August or early September what was going to happen. And that knowledge carried with it the anxiety over what would happen to all the people who worked for us, after all, these people in a real sense were my family. I wrote in a column on the last day of September that this wasn’t the worst day of my life, but it was pretty hard nonetheless.

PARTNER CONTENT