The South Pole

It’s December 16, 2019. While friends and family back home in San Diego are surrounding themselves with loved ones and dreaming of a White Christmas, Robert DeLaurentis is alone. He’s 10,000 feet above the most frigid destination on Earth, where even now, at the beginning of its summer, the average daily temperature is minus 22 degrees. He’s in the pilot’s seat of the Citizen of the World, a highly modified twin-engine 1983 Gulfstream Turbine Commander 900. Today he’s been in his cockpit for 18 hours straight, and it feels appropriate that his first human interaction since takeoff comes in the form of a joke.

As he peers through his fogged-up windshield at Amundsen-Scott Station, DeLaurentis hails its communications operators, “I’m approaching.”

“Negative, Ghost Rider,” an operator replies.

“I quickly realized he was joking and had made a Top Gun reference,” DeLaurentis says. “I laughed and said he won’t get to see the new Top Gun when it comes out, because he lives in the South Pole. It ended up being a nice human connection.”

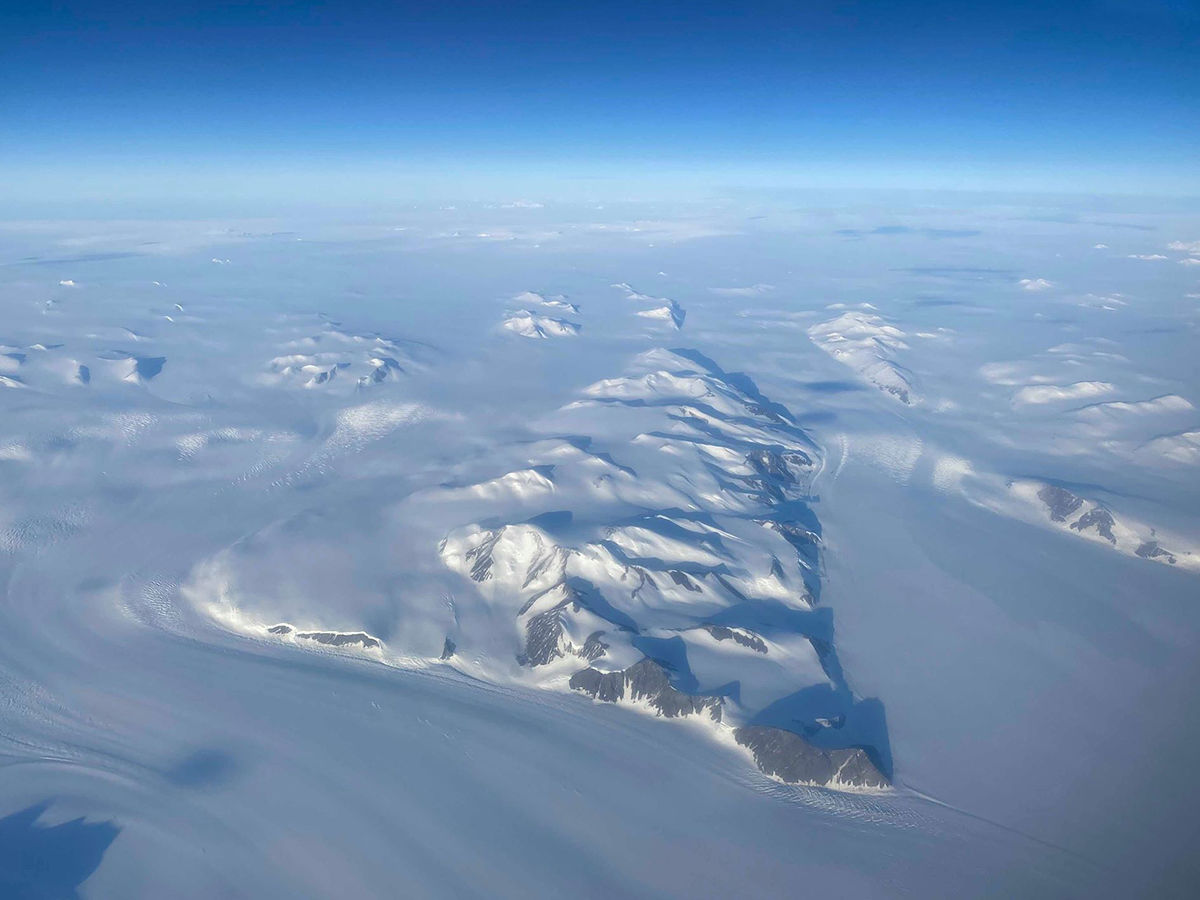

Over the South Pole, December 2019

It’s just the lightheartedness he needs after reaching the halfway point of the most grueling leg of his 26,000-mile journey—and the greatest challenge of his flying career. Coincidentally—going by the New Zealand time zone used at the South Pole station—today is also the 116th anniversary of the Wright Brothers’ first flight.

The 53-year-old San Diegan and retired naval lieutenant commander calls himself the “Zen Pilot,” and says he’s flying to the only two places on Earth where there is true peace—the South and North poles. Because of the extreme cold, only a few pilots, or people for that matter, have dared venture to either. And to top it off, his aircraft is running on biofuels.

He’s the first known person to attempt an aerial circumnavigation using only renewable fuel, which can operate at slightly lower temperatures than traditional jet fuel. Along for the ride is a four-inch “wafer-scale spacecraft” that’s collecting test data as part of DEEP-IN (Directed Energy Propulsion for Interstellar Exploration), a joint program between NASA and UC Santa Barbara’s Experimental Cosmology Group. But most importantly, to DeLaurentis the flight is about unifying people around the world.

“World peace is a difficult thing to do. But doing something that may seem impossible—like this trip—is showing people that anything is possible,” DeLaurentis says. “Each of us has a unique opportunity to be a positive force in the world.”

Robert DeLaurentis in Argentina, December 2019

The Risks

In the month since his loved ones gathered at Gillespie Field to send him off, he has headed south, touching down in Texas, Panama, Colombia, Bolivia, and Argentina. After soaring over the South Pole, he will make a few more stops in Argentina and Brazil before heading across the Atlantic to Senegal, the first leg of the journey east and north through Africa and Europe.

Today’s round-trip to 90 degrees south clocks in at 4,200 nautical miles, and it began in Ushuaia, Argentina, the southernmost commercial airport in the world. He’s arrived right on the heels of tragedy: a Chilean Air Force C-130 had just gone missing flying a very similar route to the one he was about to undertake, with all 38 people onboard presumed dead.

Still, DeLaurentis forged on toward the floor of the world. At one point the winds grew so fierce that to regain his course he had to make a 180-degree turn—putting a dangerous amount of stress on a plane loaded far beyond its factory fuel capacity. Disorientation was also a constant threat: GPS signals become more unreliable at such high latitudes, and compasses are no help, since the Magnetic South Pole is nearly 1,800 miles away from the geographic pole. When all else failed, he fell back on the celestial navigation of the ancient mariner.

Robert DeLaurentis

Nate Hoffman

Anticipating this leg of the trip kept DeLaurentis up at night. “I’ve learned that at some point you have to either accept the risks you can’t control or simply walk away,” he says. “I choose to keep flying. The opportunity to expand the boundaries of general aviation, to inspire present and future generations to live their impossibly big dreams, and to be able to fly in the name of world peace, make all the risks worthwhile.”

For some perspective on the risks involved, DeLaurentis mentions another pilot who made the trip to the South Pole and didn’t bring any survival gear, because it would’ve added 25 extra pounds to his airplane: “He thought that survival would only prolong his misery. I’m more optimistic.”

It’s a curious kind of optimism, born of having come to the brink of disaster before. Once during his first trip around the world in 2015, the single-engine plane he was flying abruptly lost oil pressure over the jungles of Malaysia, forcing him to fly without power for 19.6 nautical miles to the nearest airport.

The Pact

DeLaurentis, a native New Yorker who moved to San Diego in 1989 for naval officer training, says that years ago his life hit an all-time low. He owned a downtown apartment building that caught fire, dispossessing 24 tenants and leaving him with vacancies for months. He also had a house that he couldn’t sell for three years, resulting in a mortgage that was difficult to pay.

Overwhelmed with financial miseries, DeLaurentis says he asked the universe to make a deal with him. If he overcame his “impending financial ruin,” he promised to devote his life to philanthropy through aviation.

“Two weeks later my insurance company paid for all the repairs on the apartment building and a year’s worth of rent, my vacancies went to zero, and my house sold in an all-cash sale,” DeLaurentis says.

Pole to Pole Pilot – Robert in Plane

Nate Hoffman

Now he’s the author of two books, his 2015 debut, Flying Thru Life: How to Grow Your Business and Relationships with Applied Spirituality and, a year later, Zen Pilot: Flight of Passion and the Journey Within, which chronicles his first, east-west circumnavigation of the globe. He has flown to more than 50 countries in his travels, always in the spirit of unifying disparate parts of the world by interviewing the people he meets and telling their stories online.

He says his primary goal, shared among his donors and crew, is “to show a divided world that we are all connected.” He adds, “Our vision and intention are to connect all people through a shared adventure that includes deeper peace and oneness. One of our commitments is to be a living example of all these connections as citizens of the world and explore new ways to expand and deepen these relationships.” He hopes young people will be the most inspired by his travels. “They are the future of aviation, humanity, and the planet. They have enthusiasm to keep trying to make this world better.”

The Great Circle

In 2015, after completing his equatorial flight, DeLaurentis was ready to dream bigger. Then he came across a quote on the British Antarctic Survey website:

The concept that true peace existed at the ends of the Earth inspired DeLaurentis and dozens of friends and supporters, who raised more than $2.5 million to fund his pole-to-pole flight. The money covered upgrades to his 1983 aircraft (new high-altitude engines, long-range fuel cells, cold-weather batteries, state-of-the-art navigation systems), plus fuel, lodging, food, and insurance. And despite having thousands of hours of flight time, he still had some lifestyle changes to make before he was cleared for takeoff.

In the years leading up to the trip, he started training like an athlete. Most people may not consider pilots to be athletic, DeLaurentis says, but when you have to spend long hours in a tiny cockpit with just a few inches of wiggle room, it’s important to have a strong, healthy body. So he cleaned up his diet and worked out 1.5 hours every day, to the point where his resting heart rate dropped to 50 beats per minute. (Professional athletes tend to clock in at 40, the average person 60 to 100.) He also underwent cataract surgery to improve his eyesight, and even had ingrown toenails removed so he’d have no distractions in the air, no matter how small.

Pole to Pole Pilot – Control Panel

Nate Hoffman

On top of the physical changes, DeLaurentis had to mentally prepare for the trip, including overcoming recurring nightmares of disaster over the Antarctic. His closest loved ones, including his father, expressed their greatest fear—that this trip may cost him his life. A well-known quote among aviators, usually attributed to Captain A. G. Lamplugh, cautions that “aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater extent than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity, or neglect.” Remaining fully in the present moment is of the utmost importance—but he doesn’t call himself “the Zen Pilot” for nothing.

Though DeLaurentis will spend most of his historic trip in a cramped space, he never feels confined. He can watch as ice builds, weather systems change (sometimes to his dismay), and the sun sets “in the most dramatic fashion.” Most importantly, he sees and feels peace.

As of press time, DeLaurentis was departing Menorca, Spain. Follow the completion of his journey at share.garmin.com/citizenoftheworld or facebook.com/flyingthrulife.