It’s 10:30 on a summer night in Cambria, California, and I am standing on the Moonstone Beach Boardwalk, looking out at the sea. Thunderous waves crash onto the beach below, while, behind me, the lights from various hotels, restaurants, and streetlamps spill across the street, refracting and reflecting in the fog. When a patch of clear sky opens overhead, I crane my neck, looking up and spotting a few stars twinkling through the atmosphere, but they’re fainter than they could be, dulled by the glow from the other side of the road. In so much of California, night just isn’t as dark as it used to be.

Thirty minutes later, on a desolate Main Street where the businesses are closed for the evening, I again seek out the stars through breaks in the fog, but, this time, they are almost entirely obscured in the luminance of too-bright streetlights.

I’ve spent a lot of my life looking up at the night sky-first as a child in my driveway, and, over the last decade, as a journalist documenting some of the darkest nights on Earth. I’ve come to understand that the health of the natural world is inextricably intertwined with nighttime darkness. Gazing at the night sky in Cambria, I see both possibility and peril in the stars.

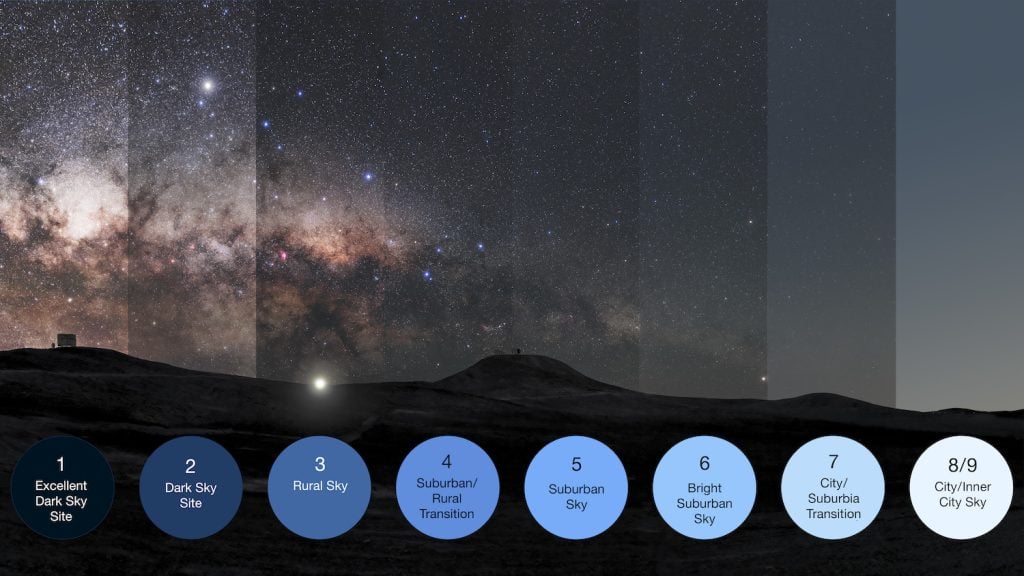

The Bortle scale which measures the impact of light pollution on dark skies at a given location.

Cambria itself is at a crossroads, trying to preserve its darkness while growing brighter by the year. Artificial light has been encroaching for a while. And Cambria isn’t alone. Communities around the globe are facing the loss of nighttime darkness. Today, more than 80 percent of the world’s population lives under light-polluted skies. In the United States and Europe, that number is closer to 99 percent. Using more than a decade of data collected by citizen scientists through the National Science Foundation’s Globe at Night project, researchers found that, between 2011 and 2022, light pollution grew by almost 10 percent per year globally the equivalent of doubling in brightness every eight years.

It would be easy to lament the rise of artificial light at night (ALAN) as simply a cost of modern living. But Claudia Harmon, co-chair of Cambria’s Dark Sky Initiative and president of Beautify Cambria, an organization founded to help bolster the local economy and improve the town, knows it’s possible for development to coexist with stars—without drowning them out. That’s why she and a small group of advocates have been working to have Cambria officially designated a “Dark Sky Community” by Tucson-based DarkSky international. If they’re successful, the town would join just two others in California, but it has already been a nine-vear endeavor.

When I meet Harmon, a 38-year resident of Cambria, we sit down to lunch, and she immediately hands me a brochure. with San Luis Obispo County’s lighting ordinance printed on the back panel. She has come prepared for our conversation, and it’s no surprise. Harmon has been among the loudest advocates for preserving the darkness in the Central Coast town.

The effort began in 2015 when she and the newly formed Beautify Cambria embraced the notion that beautification meant going beyond the initial gardening projects and public benches.

“We couldn’t really beautify our town without considering all of the town and all the things that affect the town,” Harmon says. “Bad lighting isn’t beautiful, and it’s not healthy. It’s not good for our wildlife.

So Cambria began the process of joining an exclusive club of communities that demonstrate a commitment to preserving the night sky. At the time, there was only one other town in California that had received the distinction: Borrego Springs in San Diego County. In 2021, Julian, also in San Diego County, joined the list too.

Dedicated to “restoring] the nighttime environment and protect [ing] communities from the harmful effects of light pollution,” DarkSky International (formerly the International Dark-Sky Association) has been certifying Dark Sky Places—parks, reserves, towns, and more-since 2001. Today, there are more than 200 certified locations on six continents. Most of those are parks. Just 49 are communities.

The goal of certification is to recognize areas that have “shown exceptional dedication to the preservation of the night sky.” And while that sounds simple enough, the reality is far more arduous, requiring communities to adopt legally enforceable lighting policies, hold regular dark sky educational events, monitor light pollution, retrofit publicly owned lighting, and demonstrate successful light-pollution control.

In Cambria, where dark sky events occur regularly during the winter months when the fog tends to be the most cooperative, the biggest obstacle to certification has been updating the San Luis Obispo County lighting code to comply with DarkSky International’s minimum requirements. The current ordinance is mostly compliant, but it requires a single change to include a provision for warmer-spectrum night lighting.

“I think if we can get the ordinance in front of the [county board of] supervisors, they’ll approve it,” Harmon says, but thus far, the board has not addressed the potential modification.

According to the county, it’s not quite that simple. In the planning process, “there are state mandates, things [the county] is required to do,” says Blake Fixler, chief of staff to County District 2 Supervisor Bruce Gibson. As a result, “a lot of the other things we have wanted to do have taken a backseat. It’s frustrating, but that’s local government.”

Fixler and Supervisor Gibson support the effort. “I totally see the benefit,” he says. “There’s a lot of good there,” but it’s a staff and timing issue, he explains.

Ultimately, while certification could have benefits for the community, particularly economic ones, Harmon recognizes that securing the distinction isn’t necessary to protect the night.

She keeps in mind what a friend told her earlier this year: “Claudia, just do the work. Just fix the lighting in Cambria. Do what you have to do.”

That includes convincing businesses and residents to adopt responsible outdoor lighting practices. To be dark sky–friendly, artificial light must be useful, shielded and pointed downward to prevent it from spilling beyond where it is required, no brighter than necessary, and warm in color. Ideally, outdoor lights are also controlled by timers and motion detectors so that they are only on when people need them.

Recently, in partnership with the Bluebird Inn, a historic Main Street motel built around a Victorian-era mansion, the Beautify Cambria team completed an overhaul of the inn’s exterior lighting, switching out light fixtures and bulbs for more responsible options. Harmon hopes that when other business owners see it, they’ll understand that being more thoughtful about exterior lighting can be aesthetically pleasing, safe, and cost-effective.

“[It’s] romantic,” Harmon says. “It’s nice, you know? And people feel compelled to come to a place that has that feeling.”

But the loss of night isn’t just an aesthetic issue. It’s an economic, environmental, immunological, and even existential concern.

While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how much we spend on wasted light at night, DarkSky International estimates that, globally, the amount is somewhere around $50 billion annually . In the US alone, various annual estimates place carbon emissions from light pollution between 11 million and 21 million tons.

In recent years, studies have also linked ALAN to myriad negative impacts on the natural world—corals that fail to spawn, longer infection periods for West Nile virus carriers, and disrupted circadian rhythms and potential neurodegeneration in humans, to name a few.

There’s something else, though, too. Something less tangible but equally important: Even if there were no direct environmental impacts, there would still be value in seeing the core of the Milky Way arcing across the night’s canvas, in gazing at the sky and taking in the immensity of the universe.

PARTNER CONTENT

“I think if people would look up and just appreciate the importance of what’s up there, maybe they would be better stewards of this world,” Harmon says.

Night-Friendly Lighting

According to DarkSky International, responsible lighting abides by these five principles.

- Useful

All light should have a clear purpose. Consider how the use of light will impact the area, including wildlife and their habitats. - Targeted

Use shielding and careful aiming to target the direction of the light beam so that it points downward and does not spill beyond where it is required. - Low-level

Use the lowest light level necessary. Be mindful of surface conditions, as some surfaces may reflect more light into the night sky than intended. - Controlled

Use controls such as timers or motion detectors to ensure that light is available when it is needed, dimmed when possible, and turned off when not required. - Warm-colored

Limit the amount of shorter wavelength (blue-violet) light to the least amount necessary.