AleSmith’s co-owner and CEO, Peter Zien, first fell in love with cheesemaking in 2002, when he stopped homebrewing and started brewing professionally for his newly purchased beer company. Caseiculture (the art of making cheese) had a special appeal for Peter back then; it provided him with a small-scale hobby, making something he loved to consume and share with others.

Anyone who knows Peter Zien knows that he doesn’t do anything halfway. Once AleSmith moved into its expansive new production space in Miramar (100,000-plus square feet) in 2015, he began meticulously planning a professional-level cheesemaking facility. It took him nearly four years—he had to study a broad range of cheesemaking techniques, research the best equipment to purchase, immerse himself in food-prep regulations, and pass a number of demanding licensing classes and inspections before he could actually produce anything in what became his shiny new cheese room, tucked away in a far corner of AleSmith’s building.

By last November, CheeseSmith was finally up and running. In order to get familiar with his equipment and make sure all of his procedures were in complete compliance with the city and state, Peter started production with relatively simple cheeses: Midwestern-style cheese curds. Wheels of cheddar. Wheels of Monterey jack, Gouda, and colby. Sometime in the future he will venture into more unique and exotic territory, but not until he feels everything is working perfectly with the classic recipes.

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

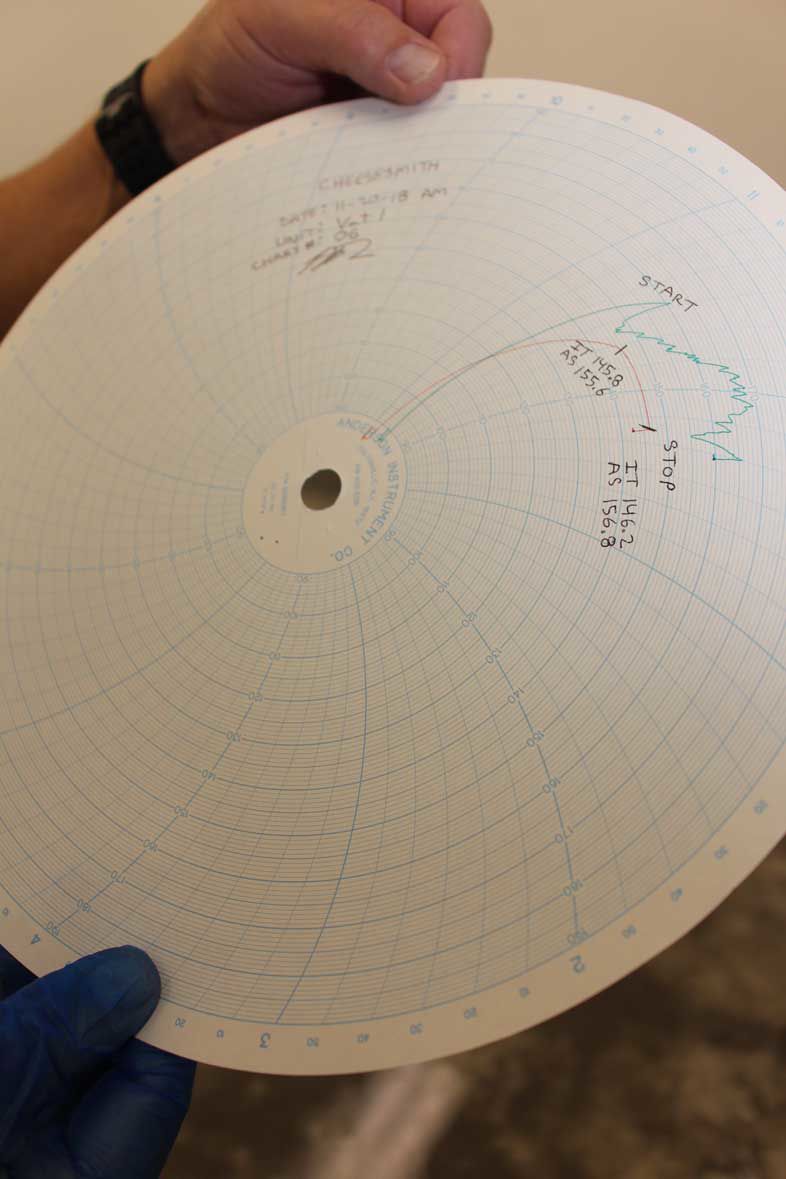

A chart generated by the cheesemaking equipment provides a detailed pasteurization record of every batch, which is required by the state

Cheesemaking scratches a lot of the same itches for Peter that brewing does; the two processes are similar in many ways. Like brewing, making cheese is mostly a solitary endeavor, requiring concentration, knowledge of technique, and precise execution. A strong dose of creativity and a great palate don’t hurt, either. “On the most basic level, it’s an ancient craft where there’s serendipity and we learned to trick nature into doing something pretty fantastic,” he says. “With beer, they didn’t know at the time that the enzymes on the grain were converting starch to sugar and—given the right temperature, water, and airborne yeast—it was fermenting into alcohol and CO2 and making beer. Cheese is similar. We have milk, and when it’s in contact with bacteria and an enzyme like rennet it coagulates and turns into fantastic cheese.”

Cleanliness is of paramount importance in both the brewhouse and the cheesery, and that, Peter says, gave him a bit of a leg up in mastering cheesemaking. He already had a strict discipline and sanitation mindset ingrained in him from brewing, so applying it to the cheesery was natural. “I always say brewers are janitors, and that’s true for cheesemakers, too,” Peter says. “After I’m done making cheese, I’ll be cleaning for an hour.” And that’s in addition to all the cleaning he does during the roughly eight-hour process.

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

When the milk first starts to coagulate, it must be broken up into small chunks

Peter’s cheesery is hidden away from public access—it’s a windowless, sterile (in a good way) space bathed in fluorescent light that feels a bit like being in a cave deep underground. This sort of isolated environment seems strangely fitting; for Peter, making cheese is almost meditative—even therapeutic. Here in his windowless room, he can become fully absorbed in his craft. No distractions. No loud machines humming and buzzing. No crowds.

It’s also the art involved in cheesemaking that moves him. “The litmus test for me was, the night before homebrewing, I used to get so excited I could barely sleep,” he recalls. “I’d be running the recipe through my head and, the minute daybreak came, boom! I’d be out of bed and making beer, and I’d be so happy. I get that same feeling with cheesemaking.”

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

As they are drained of their whey (the cloudy liquid), the curds must be pressed together to form a solid mass

Ramping up what had been a small hobby to something larger and grander is another richly satisfying aspect for him. “It was fun to scale up my homebrewing and go from a little pot in my house to seeing hundreds of gallons and then thousands,” he says. “Now it’s the same thing with cheese. When I went to the Dairy Institute at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, it was thrilling to see cheesemaking on a larger scale. I’m already experiencing that here. I was used to making two or three pounds at a time at home and now I’m making 25- or 30-pound batches, and eventually 50. So it’s a similar feeling.”

Once the brewery has its food license in place, in the coming months most of the ramped-up production will go to AleSmith for sale in the tasting room and for special beer-and-cheese events. In the near future, Peter plans to ratchet up his production to two or three days per week, eventually supplying cheese to some key retail accounts around town.

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

Finished Midwestern-style cheese curds

AleSmith is also talking about doing a cheese club, where members would receive a cheeseboard, some merch, and cheeses that would be available at some regularly scheduled interval. The cheese club concept, however, is still in its infancy. Production right now is about 50 pounds a week, and that would have to increase significantly before any additional programs become feasible (current capacity is about 250 pounds a week).

Peter plans to regularly make a variety of fairly traditional styles, but he also intends to develop some recipes that are unique to CheeseSmith—ones that incorporate AleSmith beers in some way. He’s already done a Speedway Stout Cheddar, which is based on a classic English recipe and has Speedway as a key ingredient. To make it, he drained 60 percent of the whey out and replaced it with 150 ounces of Speedway Stout from the January 2017 vintage. After the wheel was pressed, he finished the cheese with an exterior coating of Vietnamese coffee, which AleSmith also uses in some of its Speedways.

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

Peter displays one of his wheels of Speedway Stout Cheddar, which is coated on the outside with Vietnamese coffee

Other plans to use AleSmith beer in upcoming recipes include a variety of washed-rind cheeses, and other classic European styles. “I do want to develop an abbey-style that will be a signature AleSmith cheese,” Peter says. And the other styles on his wish list? He doesn’t hesitate for a second: “Emmentals and Gruyères, Swiss, and I want to do a Parmesan for grating. Basically, every kind of cheese. I don’t want to be limited.” While he’s confident he could easily come up with a cheese that works with every beer in the AleSmith portfolio, Peter is most excited to incorporate .394 Pale Ale, Old Numbskull barleywine, and AleSmith Nut Brown into future recipes.

During my eight-hour visit to the cheesery, I witnessed what can only be described as a happy artisan, excited by his craft and eager to ply it in a myriad of ways. He wants to do it all, but he knows it’s best to take it one step at a time. Peter is nothing if not patient. He says his cheeses are “just the humble offerings” he has while he tries to “excel in an art.” That’s a bit of an understatement, but he’s also humble. Cheesemaking must give a person real perspective.

At the end of the day, I say goodbye and make my way into AleSmith’s main tasting room. The contrast is jolting. Within seconds, I’ve been transported from Peter’s quiet sanctuary to the noise and bustle of a crowd. Music blares. Patrons laugh. Glasses clink. And no one is aware that the man who built the entire place is only a few hundred feet away, hand-cutting his curds in solitary silence.

CheeseSmith Is Making Cheese (Finally!)

PARTNER CONTENT

AleSmith co-owner and CEO, Peter Zien, has begun regular artisan cheese production in a venture he calls CheeseSmith