The San Diego Federal Courthouse

The San Diego Federal Courthouse

Rich or poor, center stage or just off-camera, former SD mayor Maureen O’Connor has always been a big deal—the city’s first woman mayor, whose storied political career began at the young age of 25.

An adoring public called her “Mayor Mo.”

Years after her public service, though, as she hid from the headlines and shunned the spotlight, the gaming industry had another name for her: “Whale.”

That’s what casino insiders call a big spender. For the better part of a decade, O’Connor played $500 hands of video poker as casually as a bored teen casting texts into the electronic ether. She won and lost more than a billion dollars, playing locally at Barona Casino, East Coast meccas of chance in Atlantic City, and the posh Bellagio casino in Las Vegas.

Anybody, even an iconic San Diego politician, has a legal right to gamble her own money—even if it’s an astronomical sum. But O’Connor crossed the line. After she dried up her own sizable bankroll, she illegally obtained more than $2 million from her late husband’s charity, The R.P. Foundation, and began betting with it.

She got caught last year, and the story went national. The reclusive O’Connor did just one national network interview, apologizing on camera for embarrassing her hometown, and claiming the emotional loss of close friends and a severe medical condition were behind her spate of “grief gambling.”

There’s never a good time to get nabbed by the IRS and turned over to federal prosecutors. When O’Connor got caught, she’d recently had a golf-ball-sized brain tumor removed. Following that, the 66-year-old former swim team star and physical education teacher wobbled when she walked. She had trouble speaking and writing, and claimed limited mental focus.

So much tragedy and drama intersects at uneven angles in this case. O’Connor (born a twin) was the eighth of 13 children in a middle-class Irish Catholic family. Her political achievements became monumental. She was elected to the San Diego City Council in 1971 at age 25. Soon thereafter she became the city’s first female mayor, and was a leading proponent behind public transportation and the downtown convention center. She was a role model for women in an era when the glass ceiling was much lower than it is today.

She made her political name as a populist and a champion for the working class. But after her wealthy husband died, she gained a reputation as an aloof, enigmatic heiress. She hung out with a small coterie of influential San Diego ladies, namely former San Diego Union-Tribune publisher Helen Copley and benefactress Joan Kroc, widow of the architect of the McDonald’s fast food company.

When O’Connor slowly made her way out of a San Diego federal courtroom on February 14, 2013, she was a free (albeit broke) woman, despite having confessed to illegally obtaining more than $2 million from a charitable organization. Under United States Code, the maximum penalty was 10 years in custody and a $250,000 fine.

O’Connor was granted a deferred prosecution. That means she has two years to collect the money and pay it back. And she was ordered by the court to get help for her gambling addiction.

Coast-to-coast moral indignation ensued. In chat rooms, the Joe Six-packs countered: What if I stole two million dollars! My ass would be in jail right now. Why does she get a free pass?

Why, indeed? Bankrupting a nonprofit certainly has had a fallout effect on other needy organizations in town. It also threatens to cloud the reputation of other legitimate foundations. And still, despite the two-year time limit set by the court, it’s likely that if O’Connor never pays the money back, she still won’t ever set foot behind bars.

Maureen O’Connor with her attorney, Eugene Iredale

arriving at federal court with her attorney, eugene iredale, in february 2013

The feisty, hell-raising O’Connor married Jack In The Box founder Robert Peterson in 1977. When the fast-food magnate died in 1994, Mayor Mo inherited upwards of $50 million.

Last year, the IRS saw red flags and investigated. It turns out that over a nearly 10-year span (2001–09) she won a billion dollars—but lost even more than that in high-roller gaming facilities. To cover losses, O’Connor liquidated some assets. And she maintains that the $2.1 million she got from the R.P. Foundation, of which she was a trustee, was a “loan” she intended to pay back.

The tangible results of her major transgression are severe. According to the R.P. Foundation’s tax returns, the year before O’Connor raided the coffers the nonprofit was granting out nearly $200,000 a year. Recipients of those grants included a long list of do-gooder institutions, like City of Hope (biomedical research and treatment), San Diego Hospice (an end-of-life care center that went out of business this year and transferred services to Scripps Health), and the Alzheimer’s Association.

In San Diego County there are more than 60,000 people with Alzheimer’s disease, the third leading cause of death in the region, says Mary Ball, the local association chapter president and CEO.

The R.P. Foundation’s last grant to the Alzheimer’s Association was $50,000. That was 2008, just before O’Connor emptied the till. Ball says her association’s annual budget is $2 million, and that $50,000 is certainly a sizable contribution.

“This was a tragedy for Maureen O’Connor and for the nonprofit community in San Diego,” says Ball. “It’s an opportunity lost, and that money would have been a big help.”

O’Connor’s money raid also sheds an unfavorable light on foundations in general.

“It appears there were no controls,” says Bob Kelly, president and CEO of The San Diego Foundation, an umbrella organization of charitable funds that has granted out more than $890 million in its 38-year history.

The three-person board of the R.P. Foundation (which currently has no assets) included O’Connor and her twin sister, Mavourneen, and John McCloskey, a former associate of Maureen O’Connor’s late husband. McCloskey is listed on the foundation’s tax forms as its chief financial officer.

“It’ll be interesting to see what the IRS does and what the attorney general ultimately does to those other two board members for allowing that to happen,” says Kelly. “They may not bother with the other two. You just don’t know. Sometimes they like to make examples of people. If I were the sister, or McCloskey, I’d be shaking, because this is not appropriate.”

Mavourneen O’Connor could not be reached for comment. A telephone call seeking comment from McCloskey was fielded by a woman who identified herself as Mrs. McCloskey, but the call was never returned.

The R.P. Foundation’s tax forms list Ryan & Associates of San Francisco as the paid tax preparer. The firm’s Mark Ryan declined to answer questions from San Diego Magazine.

“It was sad to see all the circumstances around this case,” says Kelly. “But it’s just dead wrong. It’s not the way you run a foundation, and it doesn’t give foundations and charitable organizations a good name. There are all sorts of rules and regulations and policies and procedures in place to stop somebody from doing something like this. But it was all just pushed aside for personal use.”

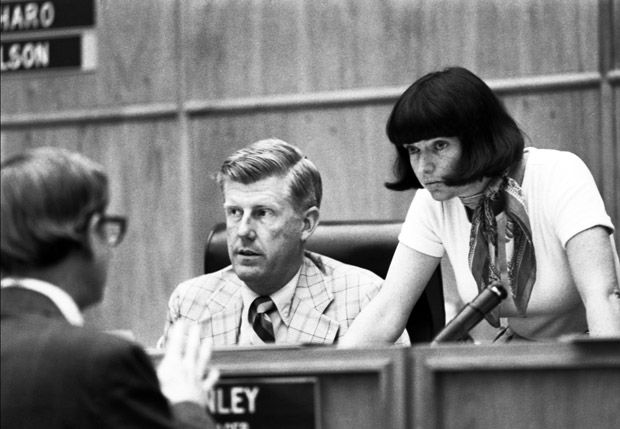

Former mayor Maureen O’Connor leading a san diego city council meeting in 1976

Former mayor Maureen O’Connor leading a san diego city council meeting in 1976

Is money on the way for Mayor Mo? Her attorney in a different case says that’s a distinct possibility.

A short while after Robert Peterson died, the O’Connor twins (and Mavourneen’s ex-husband, Tom Kravis) purchased a hotel in Mendocino called Heritage House. The property was a favorite of Peterson’s, and was immortalized as the setting for the 1978 Alan Alda movie Same Time Next Year.

In 2005, an attempt by the trio to sell the hotel to German bank WestLB went awry. A suit claims their LLC is owed $7 million (more than $12 million now, with interest), says O’Connor attorney Maria Severson.

Three years ago, Severson became law partners with former city attorney Mike Aguirre. Severson says both sides of the Heritage House case, first brought in 2009, were scheduled to meet this year—for the first time in a while.

“It is absolutely a viable claim, and it’s extremely likely to be resolved in time for Maureen O’Connor to pay back her loan,” says Severson. “That is her intention.”

Citing client/attorney privilege, Severson would not say if she meets regularly with O’Connor, or comment on her health.

“I will just say that she has suffered debilitating injuries, has some difficulties, and is not the same person she was,” says Severson.

That’s what attorney Eugene Iredale noted about O’Connor in the R.P. Foundation case. In his defense memo to the court, Iredale writes that O’Connor had a large mass removed from her brain on January 18, 2011, with a recovery that was difficult and painful.

Neuropsychologist Dr. Barbara Schrock reported to the court that O’Connor claimed “visual hallucinations such as seeing writing on the wall, blood running down staff members’ faces, or seeing individuals with number eights surrounding them.”

Schrock also reported that O’Connor complained about having a “boom box” in both ears, 20 pounds of weight gain, heart and indigestion problems, hair thinning, and difficulty in reading, writing, and expressing herself.

Iredale argued that given O’Connor’s “cognitive deficits,” a trial would “significantly increase stress and risk of continued improvement.” In asking for leniency, Iredale also suggested “compulsive gambling and lack of judgment that led to these events were themselves caused by the large brain tumor.”

Iredale’s defense memo concludes: “Maureen O’Connor has done much good over the years for the people of our city. She has committed a wrong in this case. She has suffered much. In light of all the foregoing, defendant O’Connor respectfully requests that the court accept the proposed deferred prosecution agreement.”

Maureen O’Connor with new york mayor Ed Koch (left) and New York State Attorney Robert Abrams in 1987

Maureen O’Connor with new york mayor Ed Koch (left) and New York State Attorney Robert Abrams in 1987

United States Attorney Laura Duffy weighed in earlier this year when the deferred prosecution was announced. The top federal attorney for the Southern District of California says it was imperative O’Connor not be allowed to pilfer the R.P. Foundation and avoid paying her tax obligations.

“Maureen O’Connor was a selfless public official who contributed much to the well-being of San Diego,” says Duffy. “However, no figure, regardless of how much they’ve done or how much they’ve given to charity, can escape criminal liability with impunity.”

That actually still remains to be seen.

“It’s difficult when we balance the factors in these cases,” says Phillip Halpern, a 29-year veteran of the local U.S. Attorney’s office. He’s chief of the major frauds and special prosecution section. Halpern handled the O’Connor case (and also prosecuted Randy “Duke” Cunningham, the former congressman who was sentenced to eight years in jail in 2005 for accepting $2.4 million in bribes).

“This is not a science,” says Halpern. “With Maureen O’Connor—no matter how palatable it is to prosecutors or the public at large—we had a question: Could we bring any prosecution?”

O’Connor’s health, he says, likely would have prevented that.

“The medical condition would not have played a role in an indictment,” says Halpern. “A serious brain tumor and medical complications doesn’t give her a Get Out Of Jail Free card in terms of doing the crime. The gambling at issue here preceded her hospitalization by almost a decade.”

On the other hand, Halpern needs any individual to be competent to face a trial.

“We had to convince the court to take this [deferred prosecution] plea,” he says. “The plea itself took its toll on Ms. O’Connor. Given the seriousness of her medical condition, it was a very real question of whether we could have gotten her to trial. So we had to fashion some type of relief to get the charity and taxpayers their money back.”

Halpern says it was important she come in and admit her wrongdoing.

“We didn’t get any joy out of Maureen O’Connor doing this,” he says. “But this was a significant amount of money and she should have known better. The public had a right to know about this. The easier thing to do would have been to handle it in civil court. Or brush it aside. We know whenever the department takes any position, people will say we were too hard or too soft.”

There were also other circumstances regarding the criminal act, says Halpern.

“There was no question once we had her admission,” he says. “But this was not a case where somebody falsified documents to steal money. This was a case of somebody on a board not having the right to take a loan of money. She recognized that, yet she was able to convince the head of the trust to authorize this payment.”

Would that be the now 96-year-old McCloskey, CFO of the R.P. Foundation? “The board is a matter of public record, but I don’t want to discuss that,” says Halpern, who also admits that if the $2 million is not repaid in two years, there is a possibility no one will go to jail.

“There’s a restitution order,” says Halpern. “The court can make a decision at two years. O’Connor is obligated, if she gets this money, to pay it back, whether it’s two months, two years, or 20 years, if she’s still alive. If she doesn’t get the money, we don’t have debtor’s prison any more. That’s something out of Dickens.”

Halpern pauses when asked if O’Connor got special treatment.

PARTNER CONTENT

“That’d be speculation,” he says. “We look at every case carefully and individually. We take this very seriously. We question ourselves so we don’t treat anybody harsher or easier than we should.”