Writing this column doesn’t always feel like breaking new ground. (Friend, have you heard of this little gem called Hamilton? I shall give you my hot take.) Then sometimes a world premiere by an emerging playwright drops right here in San Diego, and it’s so good that reviewing it is less like an assignment and more like standing on the street corner and flagging down anyone I can to say, “You’ve got to see this.” The Hour of Great Mercy is one of those cases.

It’s kind of miraculous how many land mines writer Miranda Rose Hall juggles here. The intersection of the queer community and church. Irreconcilable trauma and irredeemable invective. Small town life’s dual ability to suffocate and to heal. May-December relationships. American gun violence. Degenerative terminal illness. The naked fear of death. Any one of these could easily explode into schlocky movie-of-the-week territory, but somehow Hall and veteran San Diego director Rosina Reynolds have crafted a piece that faces this magnitude with honesty, maturity, and humor, without ever tripping into manipulation or melodrama.

Its central figure is Ed (Andrew Oswald), a gay Jesuit priest who returns home to the fictional town of Bethlehem, Alaska, after a five-year absence, in search of reconciliation with his brother Roger (Tom Stephenson) and his sister-in-law Maggie (Dana Case). Reconciliation about what becomes clear soon enough: Roger runs a one-man local radio show from his shed, mostly broadcasting Lake Wobegonish trivialities (the weather, birth announcements, gossip), but soon takes a steep descent into airing his family’s dirty laundry—some skillful exposition drops for the audience, as the whole town already knows about it.

That the writing and direction successfully pivot from one serious business to another, without selling any of them short, is the biggest mark in their favor. Real life seldom gives us the courtesy of neat compartments to sort our malfunctions into.

If you already know Stephenson from his recurring role as Scrooge in Cygnet Theatre’s annual production of A Christmas Carol, you’ll recognize the dark turn he’s given that template here. A deeply painful loss has festered into omnidirectional Limbaugh-like grouchiness at best, a poison tongue at worst. When he loses it, you feel for him, but also for anyone in his way.

Maggie’s stuck in the middle at first, but when she reaches her nadir reaching out to Roger as well, the guttering-candle glimpse we get of their relationship in happier times, and the chilling knowledge that some hurt is beyond healing, is just flooring. Dana Case was great in last year’s Ballast—also a Diversionary world premiere—and her edges are no blunter here.

To get into more concrete detail about just what the heck is stuck in everybody’s craw would steal some of the impact, because there’s slight misdirection at work in the first half: We’re set up to think that this town’s past trauma will be the play’s primary concern, but Ed has another shoe to drop, and—I’ll emphasize it again—that the writing and direction successfully pivot from one serious business to another, without selling any of them short, is the biggest mark in their favor. Real life seldom gives us the courtesy of neat compartments to sort our malfunctions into, of course: they bleed into one another, and often none are resolved before new ones bubble up.

‘The Hour of Great Mercy’ Faces Mortality with Dignity

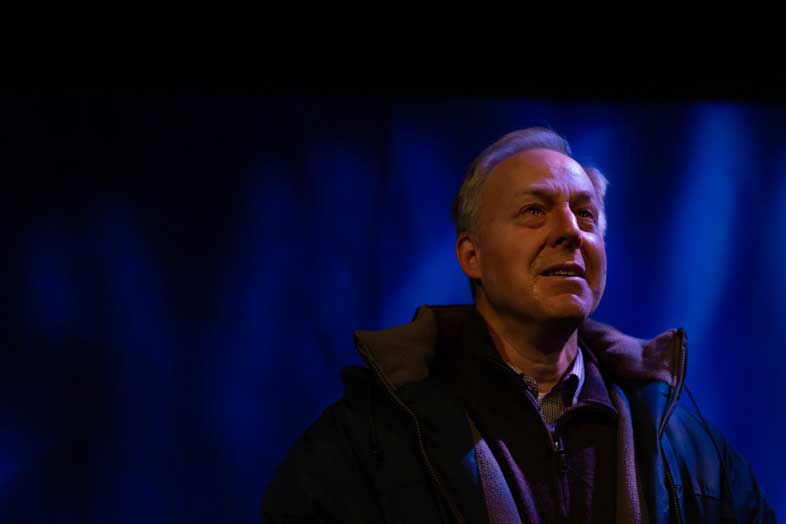

Tom Stephenson in The Hour of Great Mercy | Photo by Simpatika

Andrew Oswald’s performance is masterful. I’ve probably overdrawn my adjective account already, but he shows great control over his stage presence, as someone who’s summoning every resource he has at every moment just to maintain his dignity and hold his eyes heavenward. The unexpected relationship that develops between his character and Joseph (Patrick Mayuyu) forms the bright magnetic center of the play, a rare tenderness and a testament that it’s never too late to find love.

Eileen Rivera plays Irma, a fellow Bethlehemian who’s mostly here for comic relief. The actor is decades younger than the character, performing a sort of Little Old Lady drag that might feel out of place if she weren’t so damn funny, her optimism and pragmatic bluntness and unselfconscious singing voice so welcome in the prolonged Alaskan night. She’s no simple jester, though—because she’s inextricably bound up in the other characters’ drama, she can still flip one Greek mask for the other at the most unexpected and powerful times.

It’s rare to see a play where everyone is firing on all cylinders like this, where not a single line is wasted, and every scene holds such crucial turning points. If you’re ready to Get Real about loss, love, and mortality, The Hour of Great Mercy holds nothing back. You’ve got to see it.

The Hour of Great Mercy

At Diversionary Theatre through March 3

Tickets at diversionary.org

‘The Hour of Great Mercy’ Faces Mortality with Dignity

PARTNER CONTENT

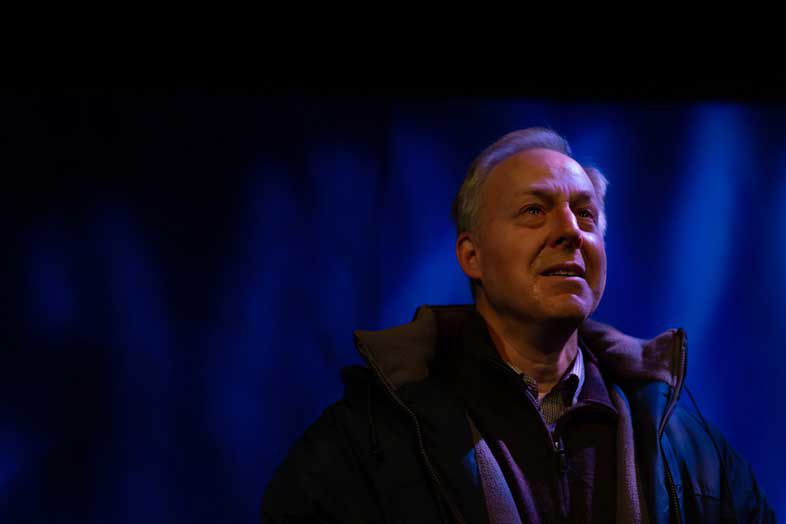

Andrew Oswald in The Hour of Great Mercy | Photo by Simpatika