Abel Garcia, Alyssa Gauna, and their baby, Ciel, at a food distribution event for military families. Hosted by San Diego–based nonprofit STEP in February 2023, the event also provided diapers, clothes, and other goods to more than 400 families

Photo Credit: Ana Ramirez

Sailor Alyssa Gauna and Marine-veteran-turned-stay-at-home-dad Abel Garcia are struggling to make ends meet in San Diego—despite the economic stability a military job presumably provides. Gauna’s latest duty assignment brought them here just weeks before four-month-old Ciel was born. “It’s really hard, especially with the baby,” Gauna says.

Garcia wears Ciel in a carrier draped with a blanket. He admits to eating as little as possible to stretch the family’s supplies. Between the couple’s financial struggles and their recent move across the country with a newborn, “it’s pretty hard for me to cook,” he says. “[I’m just making] chicken and rice—simple stuff like that. [We’re] not getting a lot of different types of foods.”

One in four members of the US military experiences food insecurity, according to the latest and most comprehensive study of this issue published by the research organization RAND Corporation, and prompted by Congress and the Department of Defense (DoD). Considering a recent, staggering rise in living costs in San Diego, it’s possible that the city is home to an even higher concentration of service members who are struggling.

San Diego ranks sixth among cities where the cost of living increased the most last year, according to the 2022 Worldwide Cost of Living Report by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The report reviewed 173 cities across the globe.

How much active service members get paid depends on rank, years served, and number of dependents. However, their salary largely stays the same at the federal level, regardless of where they’re stationed. In some locations, they may receive a Cost-of-Living Allowance (COLA), but San Diego is not one of those places, even with its soaring cost of living.

“Military pay doesn’t go as far here [in San Diego] as it does in other areas of the country,” says Tracy Owens, a project manager at Support the Enlisted Project (STEP). “Our service members are the military’s most valuable asset,” she emphasizes. “They need to be able to focus, [to] take care of their family.”

Military families wait in line for food and other staples

Photo Credit: Ana Ramirez

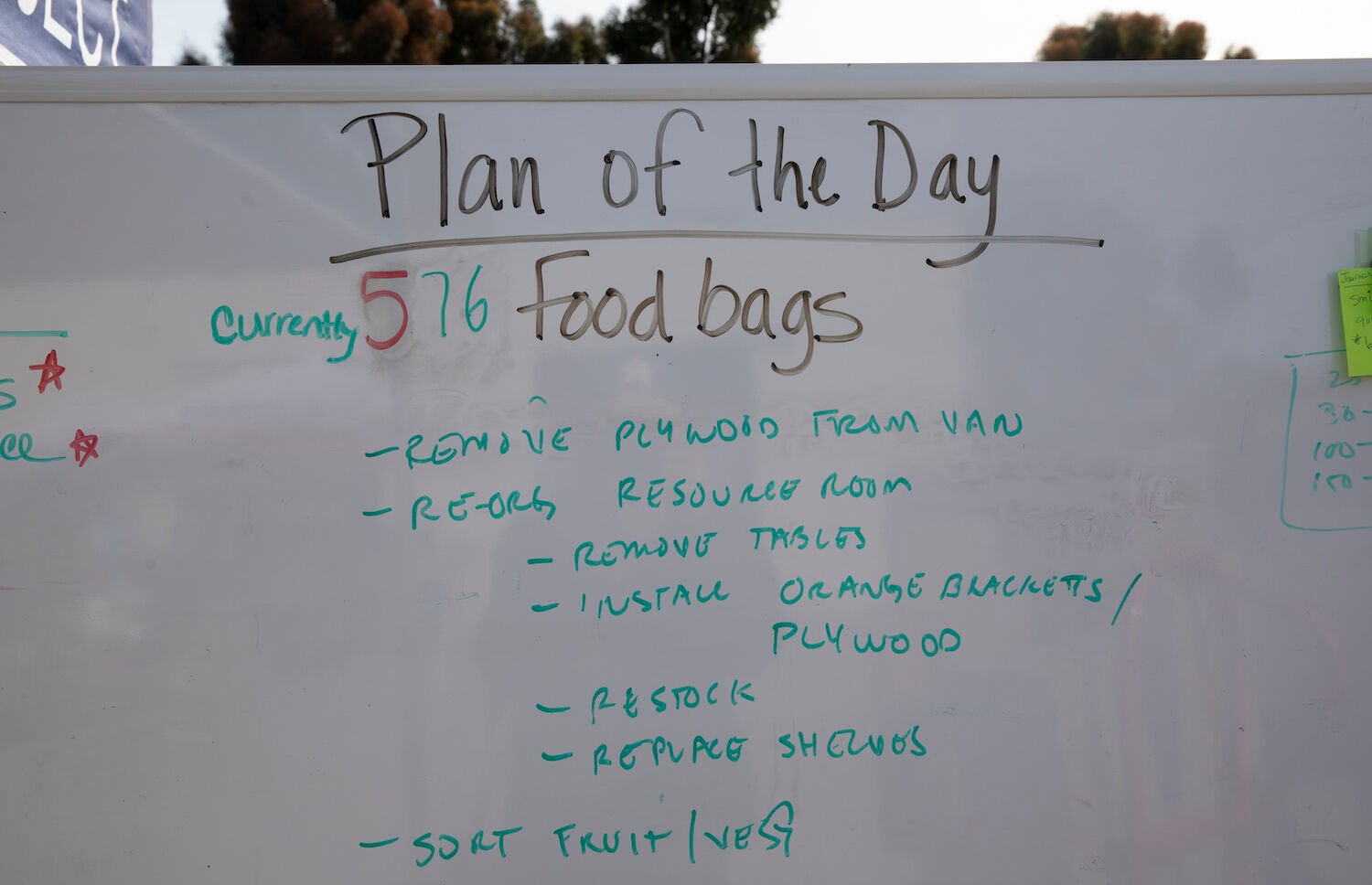

Owens does what she can to help. In the first few months of the pandemic, she started delivering groceries to military families, as well as organizing giveaways where service members and their loved ones could obtain food and other staples. At a recent event at STEP’s headquarters in Scripps Ranch, Owens helped 432 families—including the Garcia-Gaunas—access free groceries and basic household items like diapers, wet wipes, and children’s clothes.

STEP is one of many nonprofits dedicated to aiding service members and their families. Others include Courage to Call, Jewish Family Services, San Diego Military Outreach Ministries, US4Warriors Foundation, USO San Diego, Veterans Village of San Diego, Wounded Warrior Homes, and The Armed Services YMCA, along with Feeding San Diego, which provides groceries for the different programs.

“To see that our active military forces could be affected by food insecurity is disturbing,” says Feeding San Diego executive director Bob Kamensky, who served in the Navy for 35 years.

It wasn’t easy for the Garcia-Gauna family to attend food distributions. “I never imagined that [it] was something we would do,” Gauna says. “At first, Abel was not open to it. He was like, ‘We don’t need it, we are fine, we will get by.’ And then I did it. It’s something that we needed, and I think he’s open to it now because he sees how much weight it takes off us.”

In 2018, only 14 percent of those classified as food insecure in the military used food assistance programs, according to the RAND report. The study stated that “stigma—social, career, or both—was a barrier to accessing food assistance.”

Gauna went back to work after her maternity leave a month ago. She’s losing her milk supply, and formula is expensive—“as are diapers,” she adds. Currently, the family only has one car, so she drives all the way from the Naval Outlying Landing Field Imperial Beach to Miramar, where they live, whenever Garcia needs help with baby Ciel.

“If we don’t have to go grocery shopping, because we get this [food], it helps us put money aside to get another car, something we are really working towards,” Gauna says.

Military hunger in San Diego

For the Munoz family, who moved to Camp Pendleton from Virginia, the transition to San Diego hasn’t been easy, either. “It’s a shock, having the same pay, but a different cost of living,” says Navy serviceman Edwyn Munoz. “It’s [been] really hard [and] a big adjustment for us.”

The Munoz family did a lot of planning before they came to San Diego. They are money-savvy, maxing out all their retirement accounts and planning their meals to save on groceries. They bought an electric car to shuttle their three kids so they wouldn’t need to worry about high gas prices.

But all their planning couldn’t help the Munoz family when it came to facing their new reality, partly because in Virginia, Jackylyn, Edwyn’s spouse, worked as a nursing aid. In San Diego, she hasn’t been able to get a job.

“Military families face unique challenges,” Owens adds. “They frequently move, [and] sometimes it’s hard for their spouses to find a job in a new location.”

After a decade in the navy, Edwyn is an E6, a rank that, according to the RAND report, has one of the highest rates of food insecurity.

“I didn’t even know about food drives until I moved here. When we were in Virginia, we only went [to] food drives to assist as volunteers,” Edwyn adds.

Sophia Munoz, 4, rests on her father, Edwyn Munoz, during a food distribution event

Photo Credit: Ana Ramirez

At this point, Congress and the DoD are aware of how many people in the military need help to cover their most basic needs. They have commissioned studies and enacted solutions. The problem is that their efforts have seldom paid off.

Congresswoman Sara Jacobs, who represents San Diego’s Congressional District 51, is part of the House Armed Services Committee. She was involved in approving the Basic Needs Allowance (BNA), a program included in the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act(NDAA) that was supposed to increase pay to those suffering from food insecurity in the military. However, the RAND report states, the eligibility requirements for this program are so narrow that only 1,135 service members will be receiving it.

Jacobs says she pushed for an amendment that would have increased the number of recipients—but the motion failed.

“The current BNA path appears to still have far to go,” says Tony Stewart, cofounder of the San Diego nonprofit Us4Warriors Foundation and a former Navy administrator. “Progress takes a long time, and military families deserve more timely and effective pathways to eradicate food insecurity,” he says.

The DoD is also increasing the Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH) that many service members—whether or not they live in military housing—receive in areas with high rent costs, such as San Diego. According to the agency, an estimated $26.8 billion will be paid to approximately one million service members.

However, for those who are living in military housing, like the Munoz family, the BAH is not much help, as the cost of military housing goes up in accordance with the increase. “The housing takes all of it,” Edwyn confirms.

For those who live on civilian land and pay rent, Kamensky explains, “that 12 percent increase [on the BAH] is very openly advertised, and landlords follow what is happening in these allowance increases, so that doesn’t serve to deter them from escalating rent.”

The Munoz family eats breakfast together at their home in Camp Pendleton

Photo Credit: Ana Ramirez

The BAH also counts as income when applying for benefits like CalFresh, federally known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which helps low-income people afford groceries. Many military families in San Diego have a high BAH to compensate for the expensive housing costs in our region, so they’re automatically disqualified from the program.

A bill that would exclude the BAH from SNAP eligibility is also making its way through Congress. If approved, it could potentially bring some relief for military families experiencing food insecurity. “We need to take a wholesale look at this problem,” Jacobs adds. “I think this is an area in which we can have bipartisan consensus.”

As it stands, it appears any possible solution is hard to attain.

In the meantime, for Gia Ríos, a government contractor and military spouse, food giveaways like the one organized by STEP are a big help. “I just got a can of crushed tomatoes,” she tells me as we chat at STEP’s headquarters. “I already know what I’m going to do with that.”

Ríos and her family have been in San Diego since 2014. Recently, her husband was moved to a night shift, transferring the brunt of the caretaking duties to her and making grocery shopping harder. “I run home to get the kids from school and childcare, and I don’t want to take them to a grocery store—there’s no time—and then every time [I] go, [I’m] too rushed,” she explains, noting that she’s always anxious about overspending. “In the end, the bill is more than it would have been if [I] were calm and alone.”

Ríos struggles to budget with two young children, a full-time job, and all the responsibility that comes with that.

She pulls her children around the makeshift donation market in a red wagon that slowly fills with groceries, clothes, and toys. She appreciates SNAP’s giveaway, she says, because “it’s on the weekend, it’s safe, it’s not super crowded, and it’s kid-friendly. I mean, look at [my daughter]. She’s running around with a balloon.”