The morning marine layer has just burned off in La Jolla. Heat pools on the pavement. Mirages shimmer off the patio stones as a leaf blower hums somewhere in the valley below.

In the backyard of one quiet residential block, something strange juts up from the earth—an angular form clad in gleaming metal, like a shard of spacecraft wedged between rosemary bushes and stucco walls. It doesn’t look like it belongs. Then again, neither do year-round fires and routine thousand-home evacuations.

The polyhedron–shaped Polyhaus is crafted from 64 massive, cross-laminated wood sheets.

This structure is called the Polyhaus, a polyhedron-shaped, fire-resistant home covered in insulated metal panels. Instead of walls framed by two-by-fours, the Polyhaus is made entirely from 64 panels of cross-laminated timber: massive engineered wood sheets that are half the strength of reinforced concrete and burn at a rate of just one-and-a-half inches per hour, which is three to five times slower than a traditional home. A three-ply wall crafted from the material can withstand fire for nearly four hours—long enough, perhaps, to save what’s inside it, or the whole home itself.

The unique design is the brainchild of Daniel López-Pérez, the director of the University of San Diego’s architecture program. To him, the housing crisis and the climate crisis are two sides of the same coin, and the answer might just be a polyhedron. “When we come to housing production, we are back in the 19th century,” he says, “one two-by-four at a time.” The Polyhaus breaks that mold, both literally and figuratively. The angular structure goes up in two-and-a-half days; requires just three framers; and, thanks to the digitally manufactured panels with no airgaps, gives fire little oxygen to feed on.

Polyhaus architect Daniel López-Pérez.

But it’s not just rapid construction and fire resistance that inspire López-Pérez—he’s also thinking about the source of his materials. “We have become unaware of what our houses are made of,” he tells me, shaking his head. Each timber panel used to create the Polyhaus comes from Vaagen Timbers, a Pacific Northwest company that mills wood from trees cleared in wildfire mitigation projects, specifically in Washington’s Colville National Forest. In other words, he’s using forest overgrowth that could burn to build homes that won’t. “You don’t have to be an architect or a designer to have fire safety on your mind,” he adds.

Insulated metal panels protect the the home’s exterior.

And he’s right. In an age of pressboard and synthetic insulation, it’s easy to forget that shelter was once sourced from whatever the land could offer. Before mass production and fire-resistant panels, homebuilding meant something more impermanent and intuitive. In Southern California, Native communities like the Payómkawichum (Luiseño people) built kíicha, domed shelters made from willow branches, tule reeds, and cedar bark. These structures weren’t built to resist fire so much as coexist with it. Tribal-led controlled burns kept the landscape healthy, cleared excess brush, and minimized the risk of catastrophic wildfires. The land was not a threat to defend against but a partner to understand.

The arched shape of CalEarth structures helps them withstand earthquakes, hurricanes, and tornadoes, while their material composition shrugs in the face of fires.

Some are attempting a return to this intuitive partnership with the earth a few hours north of San Diego, on the southern tip of the Mojave Desert. Yuccas and Joshua trees stand paralyzed here, locked in a heat-induced trance. It’s still. Still in that way where even the breeze seems scorched out of existence. Triple digits are just the standard now. A century ago, the desert was two percent cooler and rainfall was 20 percent heavier. Today, it’s only getting hotter.

At CalEarth: The California Institute of Earth Art and Architecture, an assembly of structures peppers an open field, breaking up the monotony of beige suburbia surrounding it. They appear to have been airlifted from another planet, with domed roofs and walls made of earthen balls. Ant hills with reptilian scales.

These extraterrestrial dwellings are SuperAdobes, the avant-garde creations of CalEarth. Located in Hesperia, CA, the campus is a cluster of sandbag-built structures, each one hewn from the desert itself. Native soil and sand are stuffed into polypropylene bags, stabilized with cement and lime, and reinforced with barbed wire. Stacked layer by layer, they rise into earthen cocoons and gazebo-scale domes that feel both primitive and futuristic.

Hesperia’s CalEarth creates near-indestructible homes out of native soil and sand, cement and lime, and barbed wire.

These are no fragile art pieces, either. These buildings are meant to last. Against fire. Against flood. Against earthquakes, mudslides, tornadoes—whatever the climate throws at us next. Their secret is the arch: a timeless engineering feat that redistributes stress, letting the buildings flex rather than shatter. Square walls crack; curves endure. The domes resist seismic events and hurricanes, while their makeup of earth material stands up against increasingly large, dangerous, and expensive Californian wildfires.

At the helm of the institute stands Dastan Khalili, who began his journey with the organization at just 2 years old, tagging along on projects with his father, Nader Khalili, the revolutionary founder of CalEarth. What began as a project in the 1980s to plan for off-planet construction on the moon and Mars evolved into an educational institute teaching the SuperAdobe design—now studied by NASA and utilized by the United Nations—to students around the globe in hopes of providing a housing solution for Earth and the wildfires we’re increasingly facing.

“If you go back doing the same thing expecting different results, it’s just going to lead to another catastrophe,” Khalili says, “because the only thing that’s truly sustainable is the fire, the tornado, the hurricane, the earthquake. They’ve been here for billions of years, and they will be here long after.”

A mere three framers can put up a Polyhaus in less than three days.

He’s not being poetic. He’s being literal. Wildfire predates humans—by a lot. It’s been igniting Earth for over 400 million years, sparked by lightning strikes, volcanic eruptions, and falling rocks. These days, though, 85 percent of US wildfires can be traced back to human activity: cigarettes, campfires, powerlines, sparks off metal… the list goes on. But there’s more to it than an errant cig. The reason California is burning, and burning fast, is rising temperatures and their effect on the terrain. Climate change is causing vegetation to shrivel and brush to dry up. Droughts are the norm—about 40 percent of the state is currently experiencing one, according to CalMatters— resulting in dead trees, their carcasses a wildfire’s ideal supper. Snowy peaks are melting faster, and water tables are dropping.

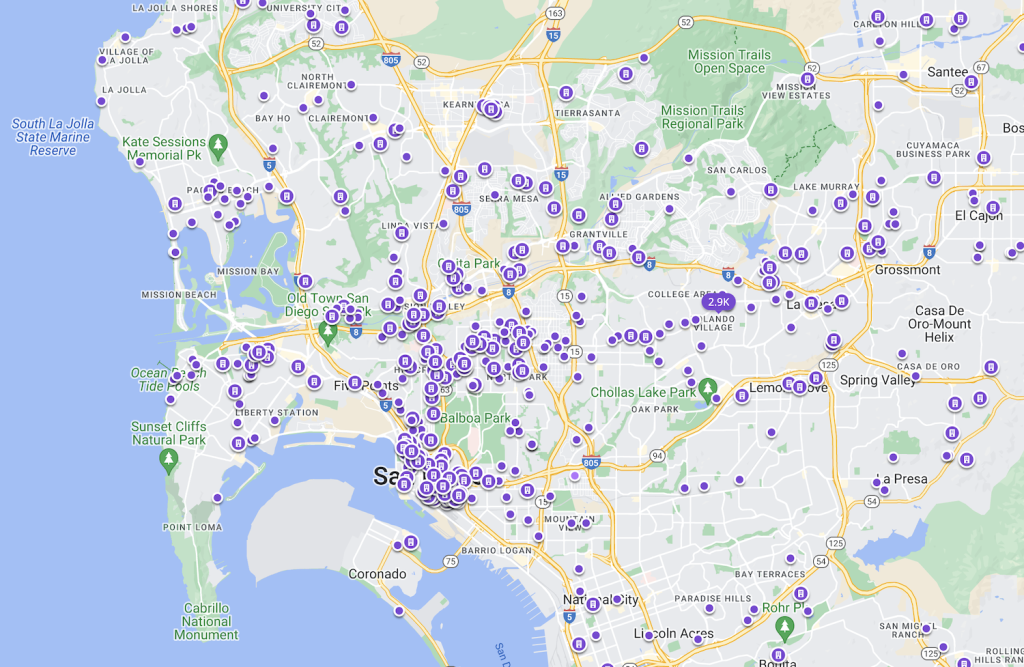

In other words, California’s changing climate has made the state increasingly prone to wildfire, and not just in remote forests. In recent years, development has pushed deeper into high-risk areas, placing more homes and communities in harm’s way. Between July 2023 and June 2024, nearly 230,000 people moved to the Golden State, many into regions already vulnerable to fire. In San Diego County, plans are approved for a 2,750-home development just north of where the Border 2 fire burned 6,625 acres in January.

Southern California has especially felt the brunt. This year’s Los Angeles wildfires brought renewed attention to the toll these disasters take—not just in acreage lost, but in homes destroyed and lives upended—after more than 16,000 structures burned. As the homes are getting closer to the flames, the flames aren’t backing down, either. Seventeen of California’s 20 largest wildfires happened in the last two decades, a stark indicator of how fire behavior is evolving and how closely it now intersects with human settlement.

The fortified materials required of IBHS-certified houses can keep structures intact for far longer than conventionally built homes—and the company set two small buildings alight to prove it.

If we can’t stop the spark, then working with the existing elements seems to be the logic guiding many architects, engineers, and homebuilders.

That’s where people like Steve Ruffner come in. As president and regional general manager for KB Home operations in San Diego, Orange County, and Long Beach, he found himself in charge of developing Dixon Trail, a new neighborhood in Escondido near a wildland-urban interface. At a builder’s conference, Ruffner witnessed a live demo from the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) showing two homes side by side: one built to 1980s housing code, the other fully fire-hardened by IBHS. The company lit both. The former burned to the frame; the latter barely flinched.

Ruffner decided that Dixon Trail deserved that same level of protection against potential fires in Escondido. California already requires homes near wildfire-prone areas to meet Chapter 7A of the state building code, including a laundry list of fire-rated materials, from roofing to vents. Dixon Trails goes a few steps further with the IBHS Wildfire Prepared Home Plus certification. This means fortified materials and defensible space—at least five feet of cleared perimeter around each home, no wooden fencing connecting houses, and outbuildings moved at least 30 feet away.

“When you have combustible items—a fence, shed, plant, tree—flames from the fire can ignite those items, leading to the ignition of the house,” says Steve Hawks, the senior director of wildfire at IBHS. Hawks is a part of the research team doing post-fire analyses, including those in Los Angeles. What he’s learned is that it’s not the wall of fire that brings down buildings, but tiny, wind-blown embers that slip through the cracks of vents or catch on a pile of pine needles by the back door.

Homes in Escondido’s Dixon Trail development meet the rigorous safety standards of IBHS Wildfire Prepared Home Plus certification.

While Dixon Trail may look like any other California neighborhood, it has an invisible coat of armor over it, made of cement siding, stucco shutters, steel garage doors, and a metal front door. The project is set to finish next summer, with half of its 64 units already sold.

Beyond peace of mind, there’s another benefit: insurance. IBHS certification is supported by insurance companies, which means homes built to the company’s standards are not only safer, they’re insurable—a growing concern in fire-prone regions where many carriers have pulled out entirely. Due to California’s Proposition 103, insurance companies can’t use wildfire modeling to assess potential risk or easily raise rates. Combined with skyrocketing wildfire losses—like the estimated $75 billion-plus in insured damages from the LA fires alone—this has driven many major insurers out of the state. As a result, homeowners are forced to rely on the California FAIR Plan, originally designed as a last resort, for coverage. But after LA, it’s cracking under pressure, too, tacking on $1 billion in extra charges to insurers and, ultimately, the homeowners trying to rebuild.

What California’s wildfires continue to make clear is this: While individual homes may be burning, it’s entire communities that suffer. The future of fire-safe living lies in building smarter neighborhoods designed to work with the land rather than against it. The innovations are here, from sandbag domes born of desert soil to geometric timber homes that burn slow and build fast. But no matter the material or method, lasting fire resilience will depend on more than the architecture. It will rely on planners, builders, insurers, and homeowners treating wildfires not as isolated events but as inevitable conditions we must live and build with.

PARTNER CONTENT

“This is not just a homeowners problem,” Hawks says. “This is an all-of-us problem.”

And that means the homebuilding solutions, like fire, will have to spread.

A History of Wildfires in California

- Before 1850: Indigenous communities in California use low-intensity burns to clear underbrush, renew soil, and shape fire-adapted ecosystems like coastal prairies. These practices are outlawed in 1850.

- 1889: The Santiago Canyon Fire, also called the Great Fire of 1889, burns over 300,000 acres across Riverside, Orange, and San Diego counties.

- 1905: The Act of 1905 creates the position of California State Forester and affords them the right to appoint local fire wardens, the origins of The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE).

- 1906: A devastating earthquake followed by massive fires destroys more than 80 percent of San Francisco.

- 1933: The fast-moving Griffith Park brush fire in Los Angeles kills 29 civilians attempting to fight the blaze.

- 1961: The Bel Air Fire tears through upscale Los Angeles neighborhoods, prompting new fire safety policies and laws in the city, including the banning of highly flammable wood shingle roofs and the implementation of a stringent brush clearance program.

- 1970: The Laguna Fire burns roughly 175,000 acres in San Diego County over 12 days. Until 2020, it remains among California’s 20 largest wildfires.

- 1991: The Oakland Hills Firestorm burns just 1,500 acres but destroys over 3,000 homes and kills 25 people.

- 2018: The deadliest wildfire in California history, the Camp Fire, devastates Butte County, killing 85 people and all but leveling several communities, including the town of Paradise.

- 2020: Burning over one million acres across six counties, the August Complex Fire becomes the largest wildfire in state history. 2020 sets a California record with 1.74 million hectares burned statewide— more than double the previous annual record from 2018.

- 2025: Fueled by drought and Santa Ana winds, fires in Altadena, Pacific Palisades, and other parts of Southern California kill at least 30 people and burn over 57,000 acres. It is potentially the most expensive wildfire in US history.