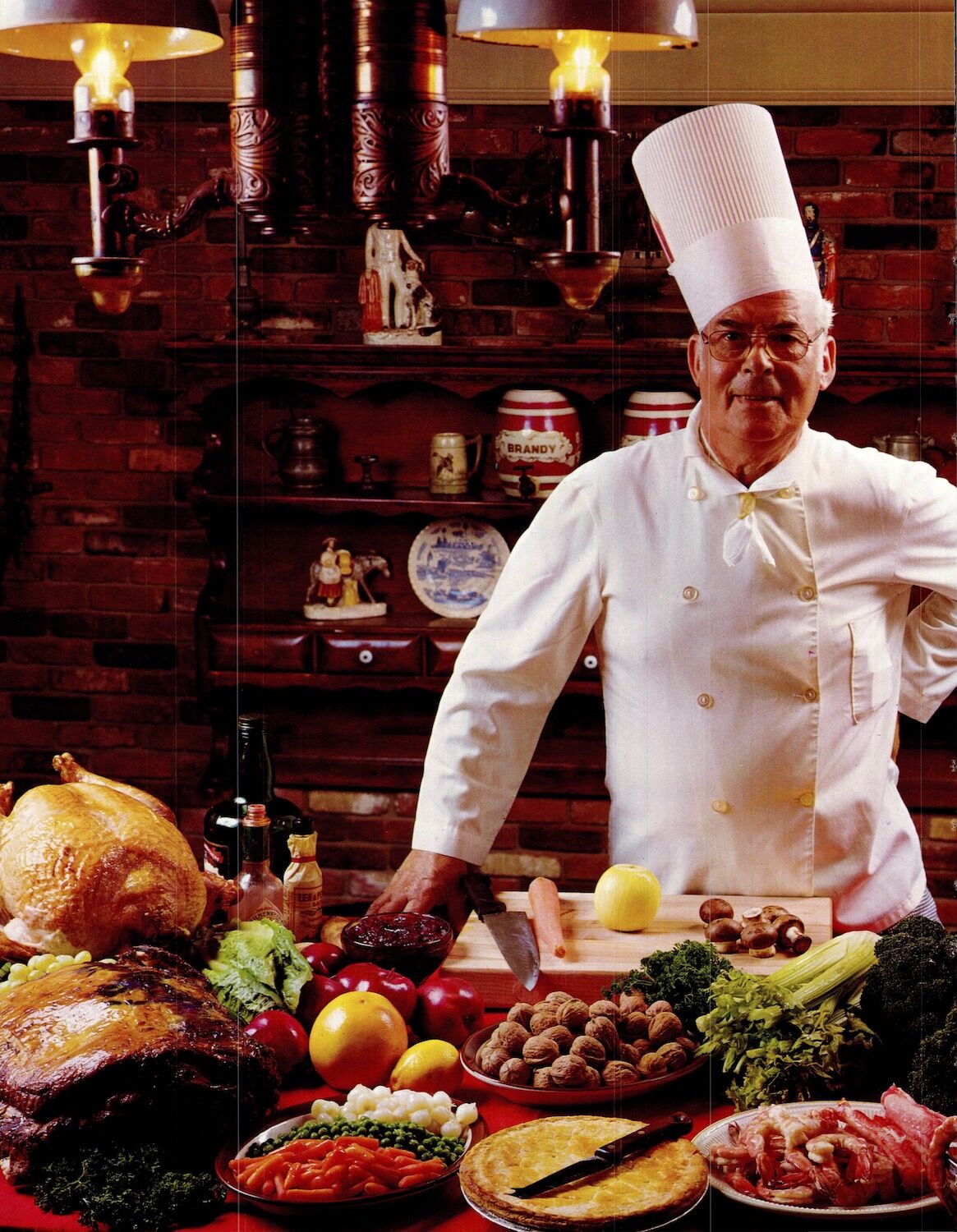

This shot of a holiday feast at downtown’s Little America Westgate Hotel appeared in the mag in 1975—but you probably already knew that, thanks to the lurid colors and napkin swans.

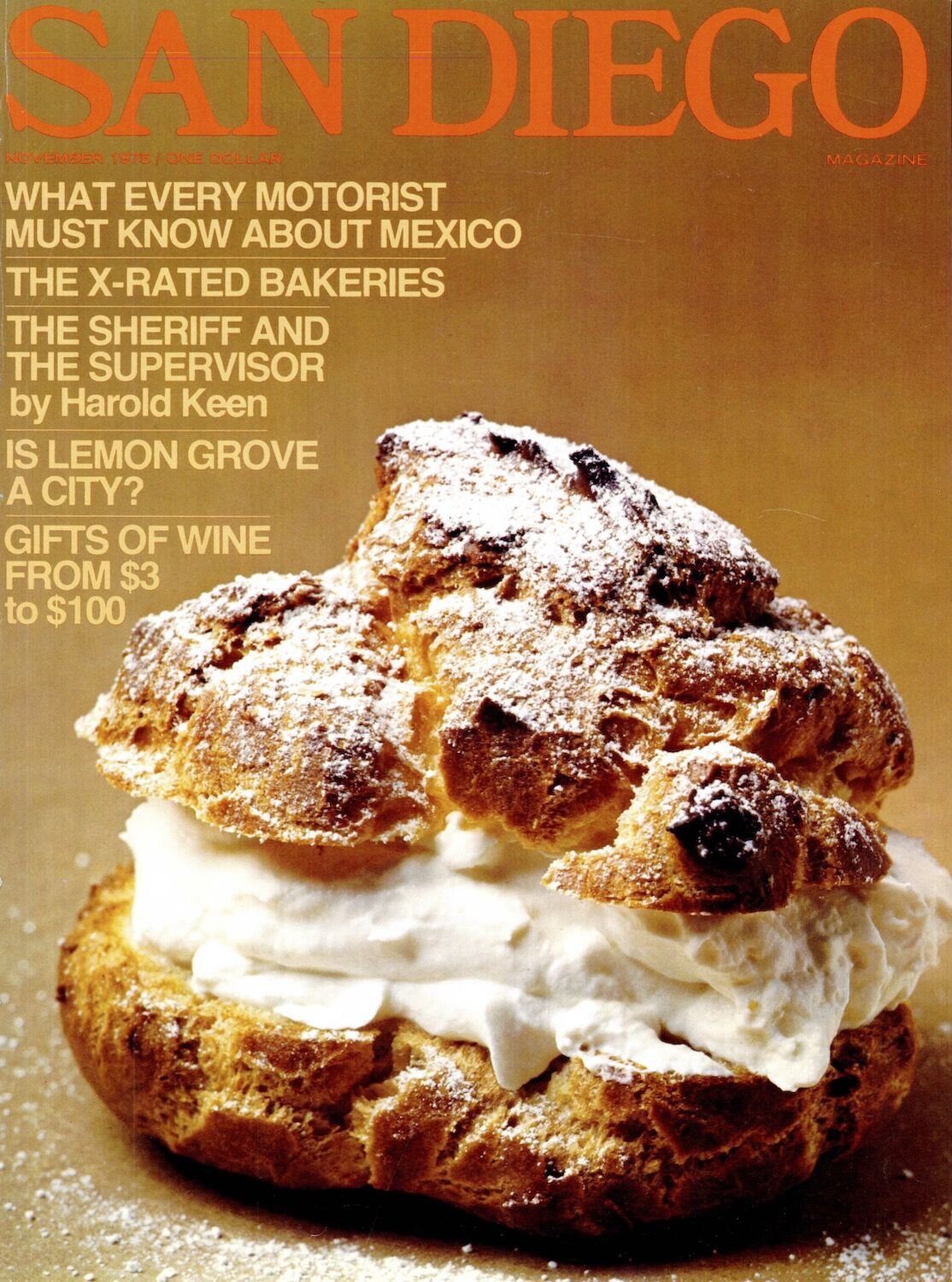

Food was first deemed worthy of cover-model status in San Diego Magazine in 1975. A single sultry cream puff, its protruding fluffy middle, come-hithering on newsstands across the city. An object of desire. Food as abs. Food as décolletage. If it were a few decades earlier, buttoned-up parents might cover childrens’ eyes from that illicit pastry smut. But this was the late ’70s, an era disco-dancing its way through one forbidden pleasure after the next.

Photographer John Oldenkamp not only shot this seductive cream puff for our November 1975 cover—he baked it, too

SDM’s editors seemed to recognize the lust they were peddling, as the headline read: “The X-Rated Bakeries.”

Of course, food writing wasn’t new. It’s cave-painting stuff. Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin penned The Physiology of Taste 150 years earlier. Twain wrote exhaustively about food. The world’s greatest cookie writer was Proust.

Food critic Tom Gable’s 1976 story describes a deluge of tips from SDM readers lauding strip-mall Chinese food spots

Brillat-Savarin was the one who coined, “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are.” That statement seems a tad pretentious in a modern food climate that’s more humble, sure. But the nugget rings true. Because the best food writing is never a discussion about how well cooks comingled their fats and acids.

Through a plate of food, you can tell entire stories of history, culture, religion, socioeconomic strata, ecology, economics, and the personality of the person making it. Shepherd’s pie speaks of Irish suffering. Birria is a story of Spain colonizing Mexico with a bunch of annoying goats. The Big Mac Index is a widely used, very real economic tool designed to analyze the strength of global currencies. Food writing took off because it attracted great writers, the poets who could juggle and sword-swallow the English language.

In 1975, William Thomson, the executive chef of a pre-Mediterranean Room iteration of the La Valencia hotel, posed for a piece on holiday eats

One of SDM’s earliest food critics, Tom Gable, would go into restaurants anonymously with a microphone in his pocket, wired up his sleeve to record his thoughts without detection. Restaurant criticism was very serious business, real covert-ops stuff. Just a bunch of hyper-literate Jason Bournes saving San Diego’s humankind from subpar soufflés.

Gable and SDM’s other great food writer, David Nelson, created literary opuses about a city and its people, using beef Wellingtons and bánh mìs as their entry points. Nowadays, food writing, even criticism, is less about playing food god and thunder-bolting your judgment and more about telling a damn good story about a place in San Diego and what it says about our city and humans at large.

San Diego Mag has always invited readers to shift their perspective, as evidenced by this innovatively angled seafood shot in our August 2002 issue

SDM’s food photography in the ’70s and ’80s was wild. US culture was focused on largesse, and this media company was not immune to the “more is more” impulse. Each photo in the mag looked like Jesus was there, feasting with a backstabber. In those early days, San Diego’s food scene had its bright spots (courtesy of restauranteurs like Gustaf Anders and Bertrand Hug), but all in all, it was not well.

Serious chefs seemed to come here to half-heartedly pre-retire—or were dragged here in the trunk of life’s car. We have the hotels to thank for ending our food dark ages. Places like the Hotel Del, Loews Coronado (which tapped in chef Michael Stebner), the Lodge at Torrey Pines (chef Jeff Jackson), and El Bizcocho (chef Gavin Kaysen) hired the country’s best talents and supported them with big banquet money from events and weddings.

SDM readers voted Mister A’s San Diego’s best restaurant in 1981. The local institution remains in our 2023 Best Restaurants issue.

SDM’s coverage during the ’70s and ’80s was all about imported foods—first from the most adored food culture in the world (France), then other European countries and, eventually, Asia. Commercial airline travel was democratized in the ’70s, and people were flying to far-flung places and coming back with tales of new foodways to enlightenment. In the hills surrounding us, San Diego farmers were growing the best produce on the planet (SD has more small farms per capita than any US county), and yet our top restaurants were getting their food from the airport.

Now-shuttered Coronado fine-dining spot Marius was declared San Diego’s Best of the Best in 1994—after, the editors noted, sneaky repeat ballots were thrown out

That changed with the farm-to-table movement in the early 2000s. It wasn’t “new.” Cooking food you find nearby is how humanity started. It just got lost, especially in the US, when the Nixon administration demanded American farms “get big or get out.” Eventually the hotel chefs led the charge back to local farms, and the wave went indie at spots like Region (led by Stebner, who would go on to help launch True Food Kitchen), The Linkery, and Whisknladle.

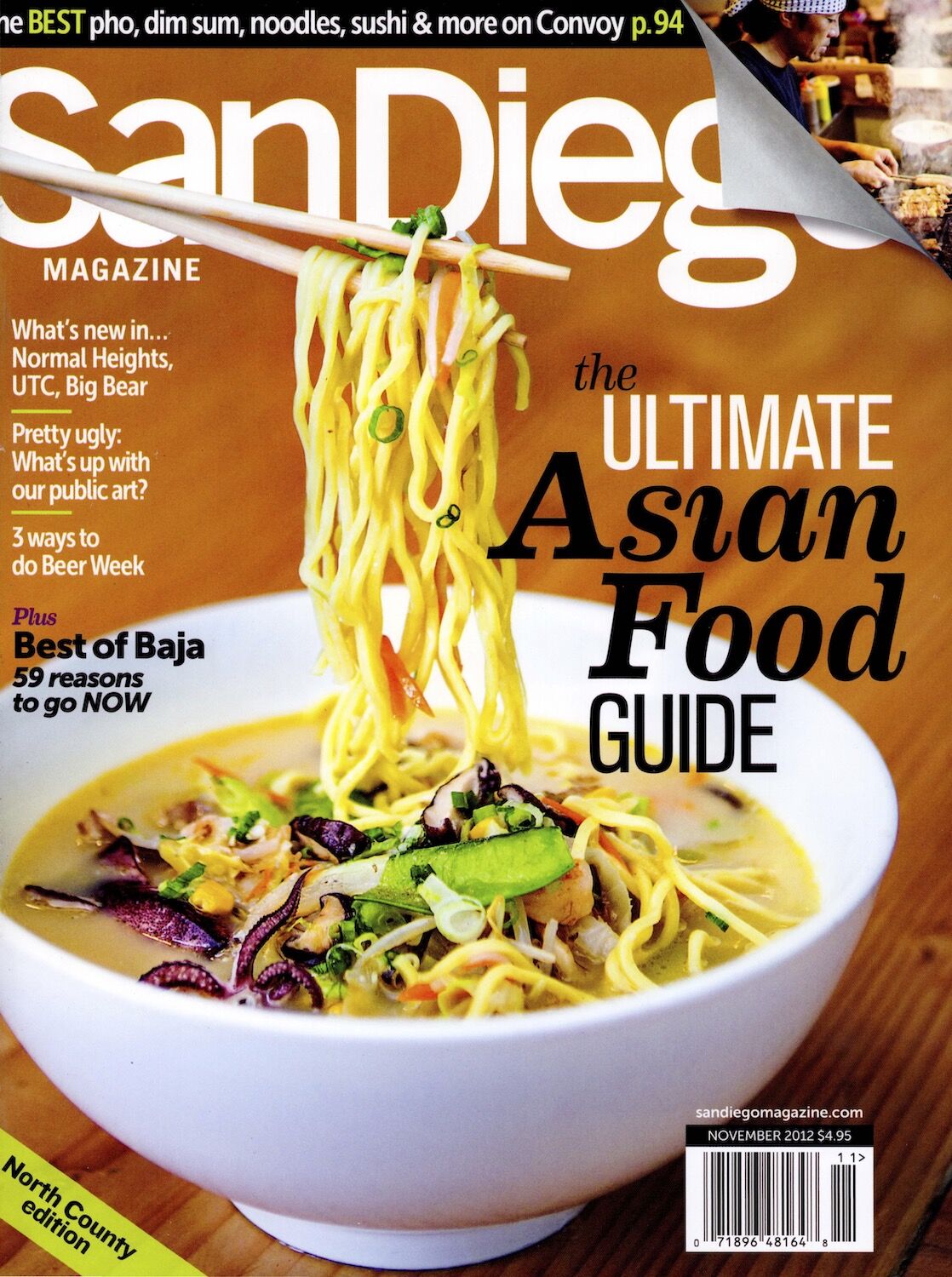

Our 2012 Asian food guide shouted out a number of still-popular spots, including Tajima, Sushi Ota, and Bahn Thai

“Food porn” gave way to ingredient porn. And most recently, both food justice and ecology became a crucial part of the conversation. SDM talked about restaurants frauding farmers; about the delicate balance between the demand for seafood and the livelihoods of the people who go out and catch it; about the work of first-generation Americans who started with their life savings and a shingle in a non-famous part of town.

Back in 2013, Troy’s number-one best restaurant pick, Addison, was yet to score even one of its now-three Michelin stars.

Food writing nearly died. Some say it has. But SDM is still pepper- spraying the coffin brokers. Our contribution to the discussion around food has always been one of longform cultural exploration, ideally with many good sentences that make you think or understand the world differently. We’ve taken our storytelling to podcasts and video and internet-friendly best-of lists that provide our readers with brief info glitter that they love, too.

PARTNER CONTENT

In 2012 (long before he and Claire purchased San Diego Magazine), Troy penned his first review for the mag, singing about the duck confit mac at the defunct Solace & The Moonlight Lounge.

It’s all part of what we do here, guiding our readers through the best meals in the city. We’ve been at it a long time.