When I was 16, someone graciously offered me a job because they heard I wanted to be a doctor. His name was Peter Zylstra, and he was the head of nursing at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Savannah, Georgia. He gave me the opportunity to be an orderly, which is essentially a nurse’s assistant—doing heavy lifting, physical therapy, patient transport, changing bedpans, and managing bed tractions. As a result, I ended up going through the process of understanding health care early, and really realizing what it means to be a doctor.

The journey is very solitary, with a backpack of experience that you throw things into along the way. You go to college, you go to medical school, you have to take all these exams (and at that time you’ve got to literally throw things in your backpack). It’s solitary because you’ve got to make the grades so you can get into residency. Then you get into residency, and you’re following mentors, but you also have a job to do. You continue to fill your backpack, but in a very solitary way.

And that doesn’t stop. You go through being an adult and a full-fledged attending physician with a load on your shoulders that has always been there. I don’t think there’s a doctor who doesn’t take their work home with them, in the sense that we’re always thinking about the patients we’ve encountered. The joy of medicine is the fact that people rely on you so much, but the double-edged sword is that it never stops. People are always asking you for your recommendations, and your solitary journey is to look into your backpack of experience and really try to find an answer. It’s not a bad thing, but it speaks to the level of dedication physicians have to their craft.

I always tell residents, before they end their training and start their new jobs, to understand that this is one of the only times in their lives when they won’t have patients to think about, when they won’t have to worry about those outcomes. In med school you learn the expression “Do no harm.” But all physicians have complications. It’s part of being a doctor, whether it’s medication side effects or an infection that occurred from a procedure. We’re not here to harm anyone at all. But I think we carry that load on our shoulders, that worry.

If I were to give the 16-year-old me some advice, it would be: You don’t have to go through the journey alone. There are people and systems around you who can help. Kaiser Permanente is an example of a system like that, and I’m grateful for the level of support each physician gets here.

I’m very proud and happy with my job choice. There are very few professions in this world where you have the ability to offer hope for patients, regardless of where they came from. They could be from an underdeveloped country or the neighborhood next door to you. It’s really remarkable that the sanctity of the relationship between patient and doctor still exists.

I think a lot about those people who have affected me since I was 16—not only Mom and Dad, but everyone. And I’m so grateful. I feel like there is some sort of calling about trying to make life better for other people, so at the end of my life, I know I’ve made the world a better place.

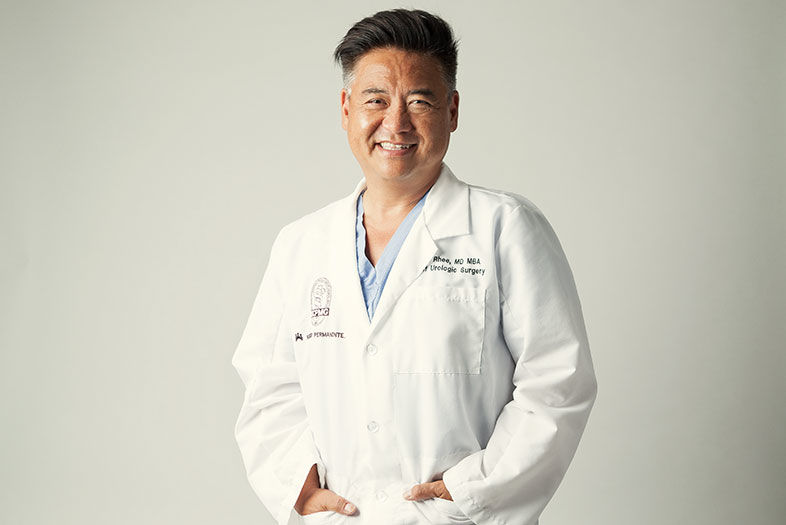

A Urologist on Why Medicine Can Be a Double-Edged Sword

Photo by Priscilla Iezzi