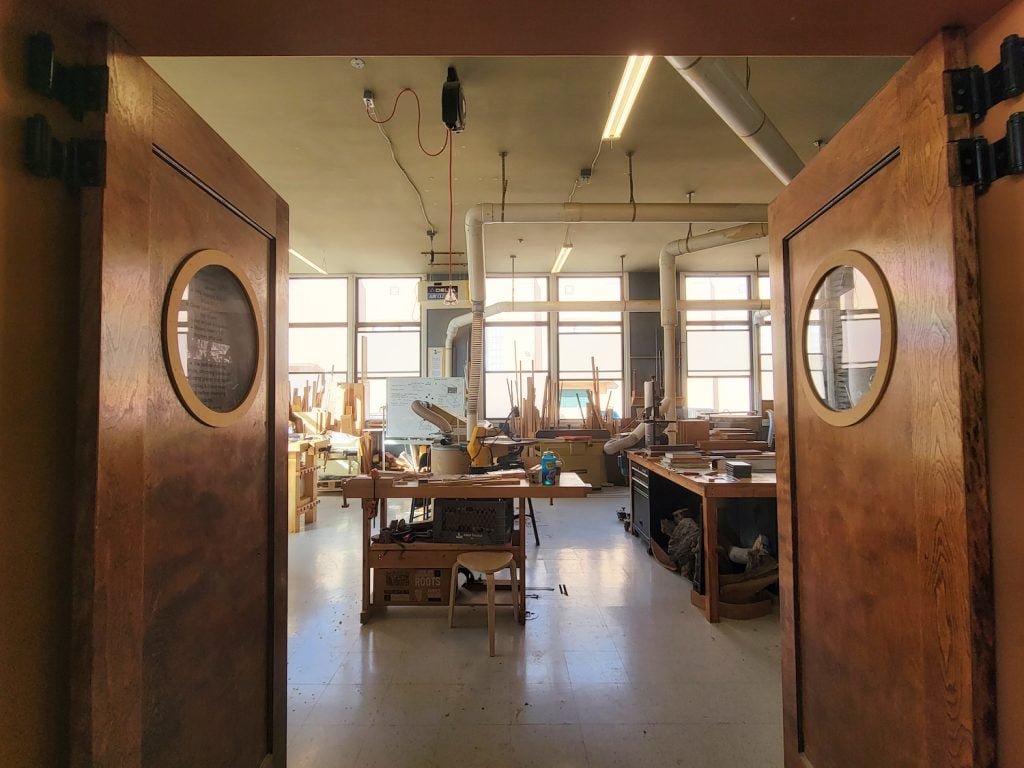

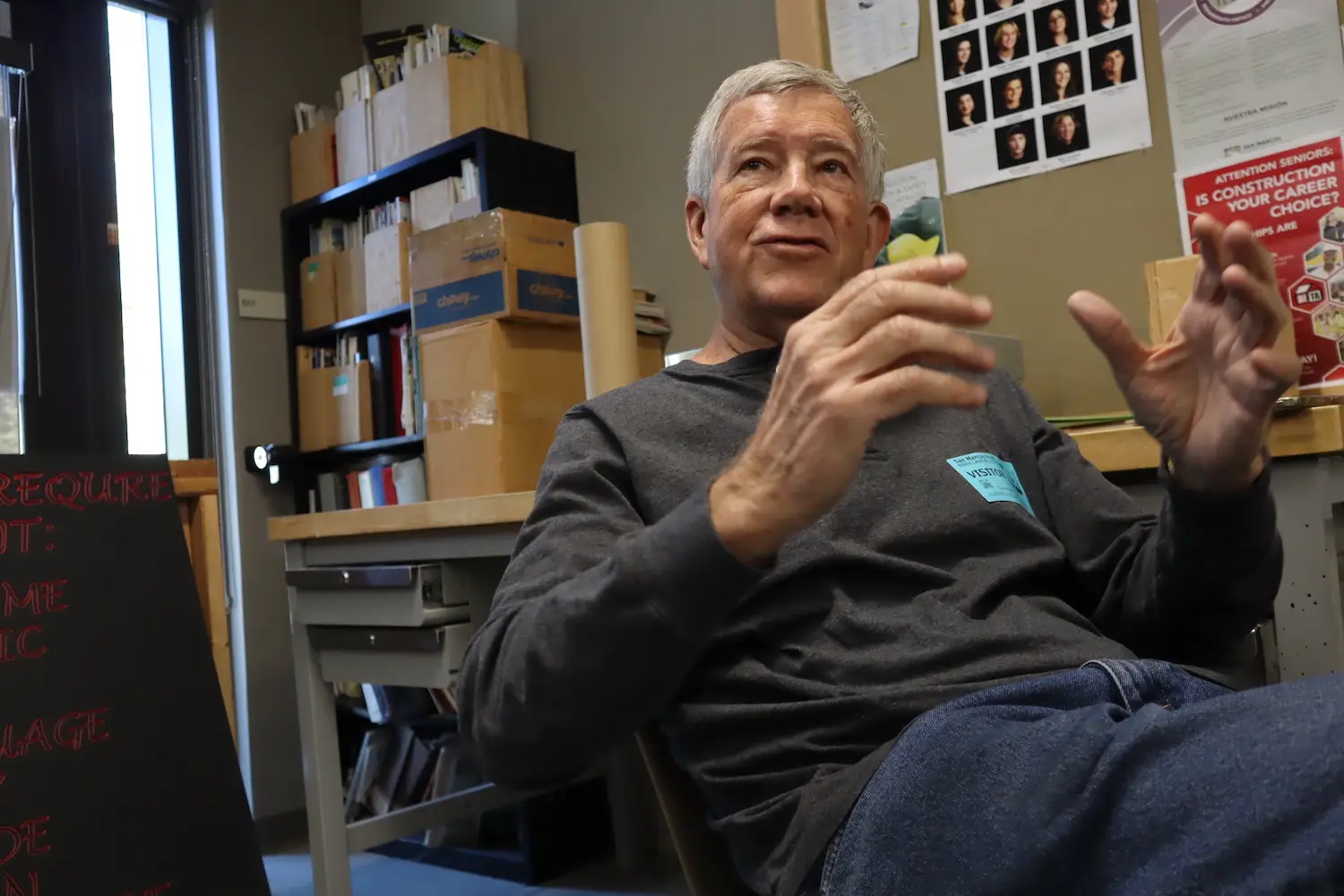

In the time before classes begin at San Marcos High School (SMHS), Warrior Village Project founder Mark Pilcher drops off school supplies for wood shop teacher Chris Geldart’s class. You won’t see him schlepping laptops or books, though—instead, Pilcher’s delivery includes materials like lumber and door frames.

“It was my idea to start building tiny houses in high school construction classes to provide houses for homeless veterans,” Pilcher says. “My vision—my goal—is to build villages of tiny homes.”

Pilcher created The Warrior Village Project in September 2019, reaching out to high schools across San Diego County to see if he could work with their wood shop classes to craft those little abodes. With help from the San Diego Building Industry Association, SMHS became the Warrior Village Project’s first partner school. Today, the program has expanded to include Rancho Buena Vista High School and San Pasqual High School.

All together, students at the three schools are in the process of constructing four tiny homes—two of which are at SMHS. Clocking in at just 168 square feet, the structures are built on trailers that are 8 feet wide by 20 feet long. Each home contains two rooms: a studio-style living space with a bedroom and kitchen area, complete with windows over the sink and by the door, and a bathroom space perched over the hitch of the trailer.

SMHS anticipates that both houses will be complete by the end of the fall 2025 semester, but that’s a rough estimate. Teachers like Geldart have to assess how fast construction can go based on their students’ know-how. Each school’s class has around 25 to 30 students, with many returning and some graduating. And in a course like shop, there’s bound to be a learning curve—especially for certain skills.

For example, the students handle plumbing and electricity, but those more finicky elements of construction require proper professional inspection. Electricians stop by SMHS to lead and oversee students’ work. If the electrical wiring isn’t done by the time their visit is over, they’ll provide further instruction, then check back again for any progress during their next visit.

“The idea is [that students] get an appreciation for what electricians do,” Pilcher says. “The hope is any student can walk out of class saying ‘Hey, I can be an electrician.’ Or, if a light goes out in their house, they feel comfortable fixing it. They’re learning life skills.”

Pilcher envisions that, as time goes on, students with less experience will learn from more adept students, and the whole construction process will run more smoothly.

After all, “[the entire class is] learning a lot from building this,” Geldart’s student Max Hackett says, gesturing toward one of the houses.

Hackett is a part of what Pilcher and Geldart call the “A Team”—a group of four advanced students who don’t require as much technical guidance as their peers. Both juniors, Hackett and Grey Boysen have taken Geldart’s class since their first year at SMHS. When he heads to college, Hackett plans to pursue a minor in construction project management.

“My returning students have a little bit more knowledge of what’s going on,” Geldart explains. “I can check in on them a little bit less, which pairs well with having a second house.”

As a result, the home overseen by the A Team is significantly further along than the other house, which is being built by other high schoolers who are new to the program or have less advanced technical skills. It’s a motivating force—students will “look around and say, ‘Okay, this is what it’ll eventually look like,’” Boysen points out.

The goal is to place the four houses in a village with eight other tiny homes and a community center, a safe place for veterans who need shelter. Pilcher has offered all four homes to Solutions For Change, a nonprofit based in Vista that recently acquired property in Green Oak Ranch.

Logistically, the program is a significant improvement over Pilcher’s original approach. Pilcher’s first house—a stick-built home started by students and completed by volunteers, member companies of the Building Industry Association, HomeAid San Diego, Associated General Contractors of America, and Seabees—was installed as an ADU at a Wounded Warrior Homes residence.

“When you build a house that way, the plans have to be approved and the home has to be inspected by the jurisdiction where it’s going,” Pilcher says.

Stick-built houses are traditionally constructed and inspected onsite. But that inspection process—and ensuring that the house follows the specific policies and laws of the city where it’s headed—becomes significantly more difficult when students build the structures on campus.

The Warrior Village Project’s second house sat until it was eventually sold; Pilcher was unable to find a suitable site in a cooperative jurisdiction. Using that money, Pilcher pivoted to tiny homes.

“We couldn’t make it work under that model,” he says. “[We now create] movable tiny houses, which are built to a national code, so it doesn’t matter where they’re going. We still have the zoning and permitting issues to deal with, but that’s getting better all the time.”

PARTNER CONTENT

Back in Geldart’s classroom, construction wraps, with students putting away materials and sweeping away dust and debris with brooms. Tomorrow, they’ll pick up where they left off—again and again, until graduation.

“It’s not perfect, but it’s trial-and-error,” Boysen says. “It gets better with every iteration—every graduating class. Then, the next class will come over, and they’ll start a new house.”