Luthier Shawn Weimer plays one of his custom guitars inside his studio which he shares with his wife, a local ceramicist.

Photo Credit: Marius Ladner

In 2008, Shawn Weimer and his wife, Sally, lost their 12-year-old son in a zipline accident. A tragedy that shattered his family and left him ready to take his own life. “A couple of times, I had a gun to my head in a hotel,” he says. “I was like, “I can’t fix anything anymore. I’m worthless. I’m just taking up air.’”

As we talk, we’re inside his Oceanside shop, where he builds custom guitars. Like many great studios, it’s disordered. Deconstructed guitars hang on shelves above, and wood dustings dress the concrete floors while layers of tape, glue, gloves, eyeglasses, paper sketches, and tools take up residence in any available space.

What began as a college pastime around 1986 is now a full-time business, branded Zoe Guitars, a nod to his family who kept him going.

A collage of wooden shapes and colors flood Zoe Guitars’ Oceanside studio waiting to come to life.

Photo Credit: Marius Ladner

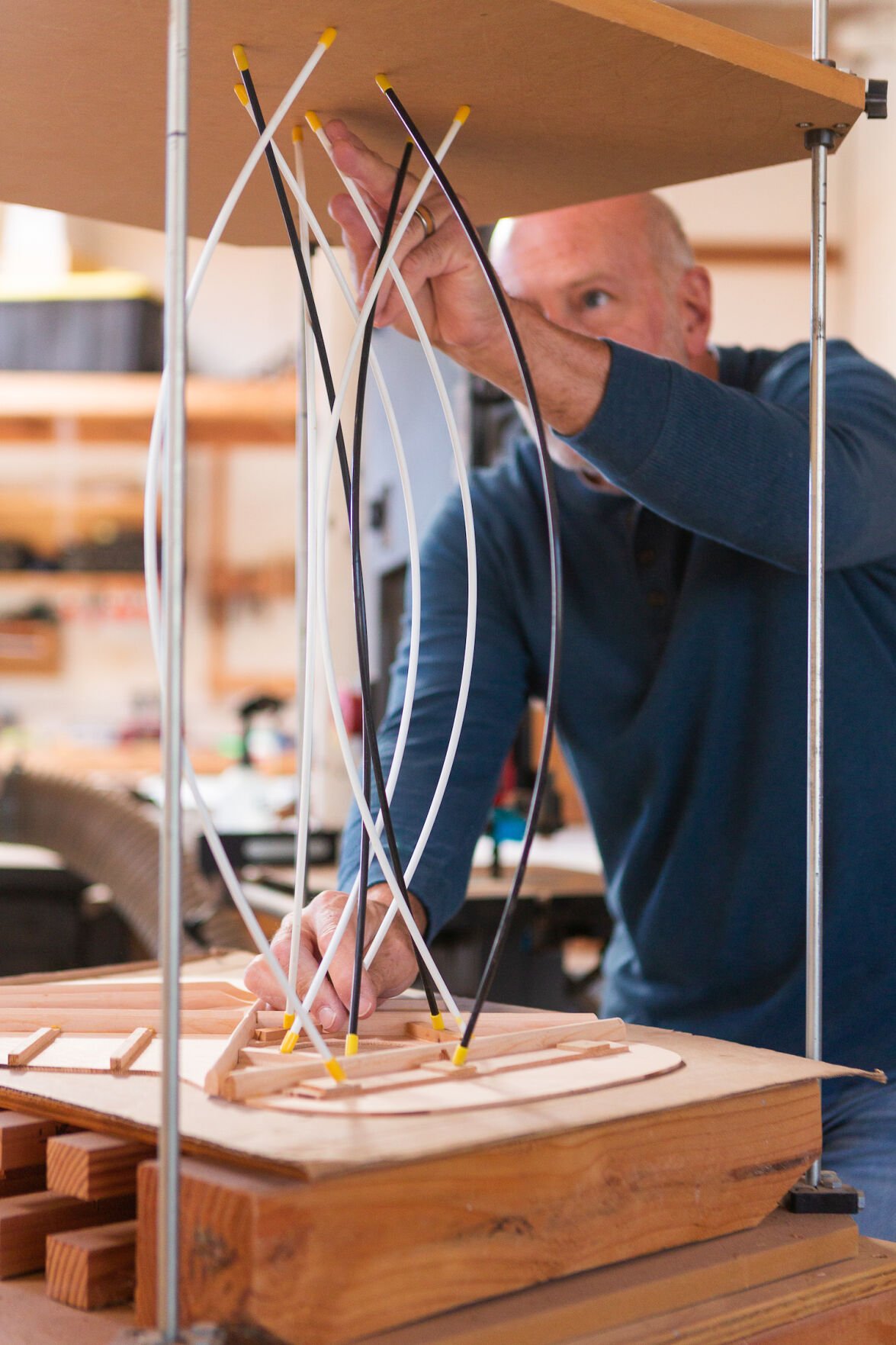

In worn jeans and a light blue thermal, Weimer teaches me about guitar bracing. The centuries-old art is a method that determines how each tone bar is laid out and shaved down to reinforce its top and back and shape its sound. Musicians rely on this perfect balance of bracing, positioning, and weight to create vulnerable and complex sounds that complement their vocals.

“[You’re] putting smaller and smaller scratches in it until you can’t see them anymore. That’s the only way to get a perfectly glass-smooth finish,” continues Weimer as he demonstrates how tiny cuts on the wood refine each guitar. “If anything can be scratched, it can be polished.”

A luthier will go through around 20 laborious steps before finishing a guitar. The specific woods used, the shape of its body, fret spacings, the strength of its neck—everything must be meticulously mulled over to allow it to sing.

Weimer’s understanding of life’s many pressures and constant scratches—the ones that slowly break us down, change our shapes, and soften us to become stronger humans—is central to the founding of Zoe Guitars.

Weimer demonstrates how the wooden bracings are placed behind a guitar’s top to ensure it doesn’t break under the weight of its strings when played.

Photo Credit: Marius Ladner

Before his son died, Weimer ran a media production company. When he found that money wasn’t bringing him happiness, he set off with his wife, son Zach, and daughter Kelly to do good in global South countries. He wanted his children to gain a bigger perspective of their privilege.

Zach’s life was cut short nearly two years later. Though his family continued their international work, Weimer remembers that time as a way to numb the pain rather than facing it. “I didn’t know how to heal,” says Weimer, who fiddles with a guitar pick as he speaks, his pauses occurring longer between words.

Eventually, he and his family found their way back to San Diego, where he channeled his pain into building guitars, though the numbness remained. In 2015, he welcomed his first grandchild, Zoe. Her name would restore his purpose.

Zoe Guitars, shaping

Photo Credit: Marius Ladner

“If you really look at the Greek meaning, it means, ‘Not just living, getting through,’ but more like, ‘instead of just surviving, thriving,’” shares Weimer. “I thought, ‘I’ve got to start living again.’” That same year, Weimer became a professional luthier and opened Zoe Guitars. Today, he leads me through his studio with excitement; there’s joy in his face, hope in each wrinkle curling up around his eyes.

“Anytime you leave [the tone bars] really thick like this, the top can’t vibrate as much. So, you lose bass tone on the bigger strings, and then on the skinny strings, the whole guitar becomes more treble-y,” Weimer says as wood shavings fly off the bars onto the ground around him. Tapping on the soundboard, he listens for these tones. Shaving, listening, shaving, listening.

There’s reverence in this room. An understanding that the delicate instrument in front of you tells you how it should be built. But there’s more looming in the air; it’s a sanctuary for restoration. With each new guitar Weimer builds, the hours spent shaping, shaving, starting, stopping, and listening, the healing continues.

PARTNER CONTENT

Zach’s memory is there. It’s what makes his guitars so special.