The billiard-green strips of poblano peppers on the paper plate in front of me are potentially worth millions of dollars. A member of the culinary team has used a black Sharpie to divide the plate into two sections. On one side, the veggies are roasted, on the other they’re sautéed. If the two men sitting at the corners of this table like either option enough, a biblical flood of poblanos will flow into the American marketplace.

One of the men is culinary director Justin Mosel. The other is the snowy-haired version of a college kid who, in the ’70s, returned from a Mexican surf trip with a tan and a recipe. Scribbled on a piece of notebook paper and carried unused in his pocket for years, that recipe would create an empire.

“I like the sautéed peppers better, more vibrancy,” Ralph Rubio says to his team before adding, to me: “We just launched a vegan option. The whole flexitarian thing is growing. You don’t have to be a vegan to want a vegan meal.”

Now 64, Ralph has a preternatural calm usually seen in spiritual leaders or at last call. His cheekbones aren’t merely pronounced, they are geological. So when he smiles, he expresses something both grandfatherly and childlike—a Venn diagram of trust. And he smiles a lot.

“This is Ralph’s seat,” Mosel told me when I entered the test kitchen for Rubio’s Coastal Grill. Having a seat at the table is important to Ralph. Eventually, during the three-to-six-month process of testing each new item, Rubio’s “Beach Club Members” will be invited in to try the dishes and give feedback. The test kitchen has its own Yelp page (five stars).

Rubio’s corporate headquarters is in Carlsbad, at the geographic center of their 117 quick-service restaurants throughout Southern California. (There are 196 Rubio’s total through five states, mostly in the Southwest, but also Florida.) One wall of the waiting room has a blue-lit tank populated with tropical fish. The opposing wall—above lime-green chairs, on brand with Rubio’s color scheme—is one of the world’s most famous recipes on how to batter and fry a fish.

Ralph Rubio fish taco king

One of Ralph’s favorite fish taco stands in San Felipe.

The Big (Spring) Break

While a freshman in Zura Hall at San Diego State University in 1973, Ralph was invited by some upperclassmen on a trip for spring break. “San Felipe, what’s that?” he remembers saying. “They said, ‘We’re going to camp on the beach in Mexico, drink beer, dance, and party.’ I said, ‘Well, sign me up.’”

When they arrived at a little fishing town outside of San Felipe, makeshift stands everywhere were selling fish tacos—beer-battered and fried whitefish, served in a corn tortilla with cabbage and crema and salsa and lime. Unlike many Americans, Ralph didn’t flinch at the concept. He and his friends ate them for breakfast, lunch, and dinner with ice-cold Corona (whose distributor was four doors down from their favorite stand). Every year they went back and did it again.

“One night in 1975, we took a break about 10 p.m.,” he recalls. “It’s dark, it’s festive, and I go, ‘Why is no one serving these in San Diego like this, with cold beer? Look at all these college students loving the experience.’ That’s when the light bulb went off.”

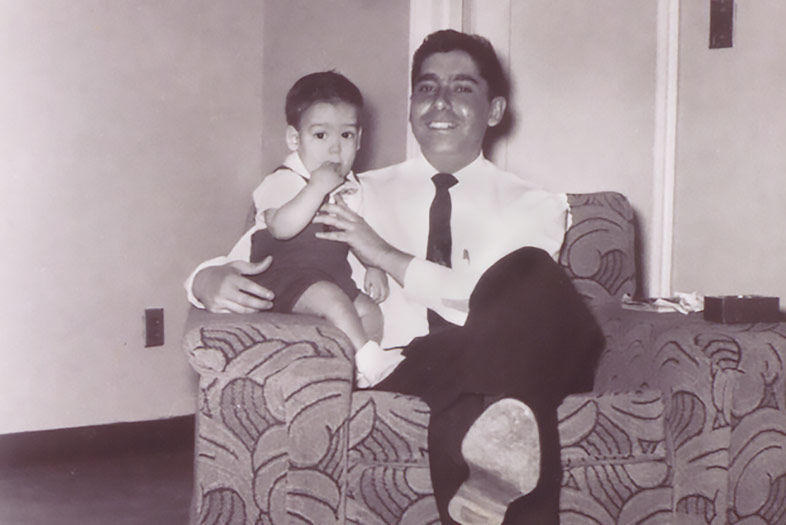

Ralph Rubio fish taco king

A young Ralph with his dad, Ray.

Ralph felt if he could open a fish taco stand in the US near college kids and the beach, he might not need his backup career plan—becoming a teacher, like many of his relatives. He asked Carlos, the cook at his favorite fish taco stand, if he wanted to come to San Diego. Carlos said no, not really, thanks. “‘Ok, well… then can you tell me what’s in the batter recipe?’” Ralph asked. “All the rest—the crema, the lime, the cabbage, I could figure out—but the batter was the key.”

Carlos gave it to him—flour, mustard, garlic, oregano, pepper, water.

“I carried that piece of paper around with me for eight years,” Ralph says. “Being 28, 30 years old, you’re not too organized. Thank god I kept it. It was obviously important to me.”

Ralph amassed restaurant experience as a busser, waiter, and manager at chains like The Old Spaghetti Factory, Hungry Hunter, and Harbor House. Eventually his dad, Ray (who immigrated to San Diego as a teen, took a job sweeping floors at a plastics factory, and eventually became one of the top plastics industry consultants in the country) offered to give Ralph $70,000 to start his “fish taco idea.”

The Rubios found an ad in the paper for a spot on Mission Bay Drive, a Mickey’s Burgers that had previously been an Orange Julius. Mickey wanted $80,000. Ray said they couldn’t afford it, since they’d need money for improvements and operating capital. He told his son to sit in the 7-Eleven across the street and count the customers at Mickey’s to get a real evaluation of its worth.

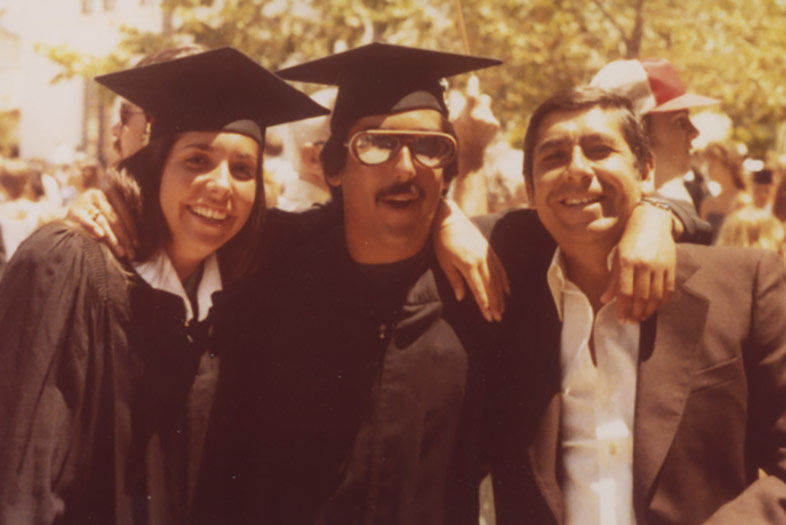

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

Ralph with his sister, Gloria (left) and dad, Ray (right) at their graduation from SDSU in 1978.

“So I did, with a pad and paper on my lunch breaks,” Ralph recalls. “And come to find out, he had no business. The figures he had shown us weren’t real. My dad told me to offer him $15,000 cash. I said, ‘Are you serious? C’mon, that’s insulting.’”

Again, Ralph did as his dad asked. Mickey yelled at him—called him a rude young punk—and hung up. Later that night, Mickey called back in tears. He needed the cash, and agreed to sell.

Next, Ralph met his dad at Spiro’s Greek Cafe and negotiated terms for their new venture. “I just wanted a loan, but my dad said, ‘Oh no, I think equity’s going to be better,’” Ralph laughs. “So I offered 70/30. Nope. 60/40. Nope. He got me down to 50/50.”

Over the next few months, the entire Rubio family—Ralph, Ray, mom Gloria, and siblings Gloria, Robert, Richard, and Roman—painted tables and signs and built a fish taco stand. They didn’t do a soft opening, where you test your concept with a small and forgiving number of friends.

“We just opened the doors and figured we’d let a few people in to test it,” Ralph explains. “Well, turns out all those cars driving by had been watching us. There was a line out the door. None of us had made food to scale. Probably half the orders I made were mistakes. I had to give people money back. It was a disaster. I was almost in tears.”

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

The first Rubio’s location, which opened in January 1983 on East Mission Bay Drive.

The initial rush didn’t last. They were only doing $200 a day in the beginning. The idea of a fish taco doesn’t seem strange these days, but in 1983, it sounded pretty weird/gross/oh-hell-no to Americans who hadn’t surfed in Baja (which was almost all Americans).

“If you didn’t go to San Felipe, you didn’t know what it was,” says Ralph’s brother Robert. “A lot of our promotional budget was giving a free fish taco. All the testing we did, 75 percent of people who tried it ordered it again. The whole slogan was ‘One bite and you’re hooked.’”

Slowly, the buzz about Rubio’s and their weird fish tacos grew. Ralph still has the sales charts from that first year, and he says the line goes up steadily every month. Then, after they opened their second store near SDSU around year two or three, Rubio’s exploded.

“We had people drive down from LA and Orange County just to go to Rubio’s,” says Robert. “It was a destination. That first store was like the first Tommy’s burgers in LA.”

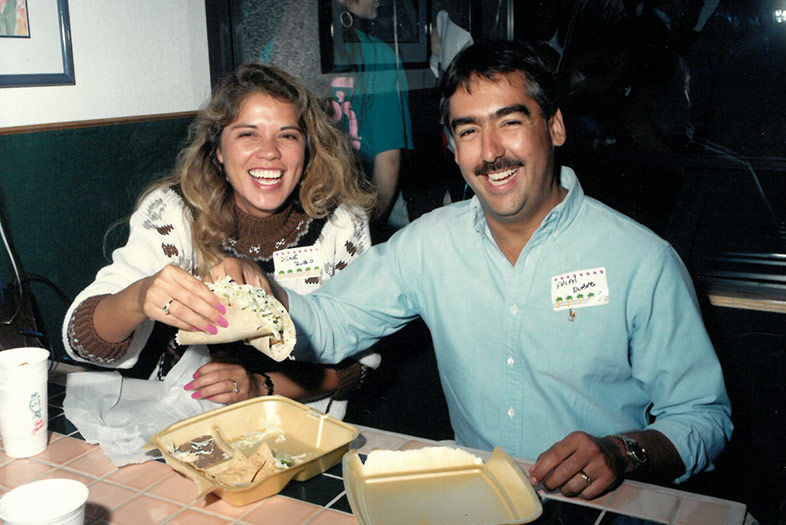

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

Ralph and his wife, Dione, at the grand opening for Rubio’s Encinitas location, 1989.

Small Fish, Big Pond

To understand the zeitgeist Rubio’s tapped into with its first store in Pacific Beach, we have to imagine a time before the internet—specifically social media. Nowadays, Instagram and Facebook are indexes of what the world eats, shown in high-resolution photos, often with recipes. Food discovery has become a global obsession. This second-by-second archiving means there are very few dishes in the world, even in the most remote villages, without a hashtag.

In 1983, however, the internet was still futurist babble. The only way you could find out about fish tacos in Baja was to get in your car and drive to Baja. In the ’70s and ’80s, Americans viewed Baja as Shangri-La, a dusty, remote otherworld for the bare-chested and free. Surf culture was taking over the American dreamscape, American surfers in Baja became heroes of wanderlust, and what those heroes ate was fish tacos.

Historically few food combos have received such mystique by association. At Rubio’s, Americans could be transported to San Felipe without ever crossing the border.

Had Instagram existed back then, it’s unlikely that Ralph could’ve kept the recipe in his pocket for eight years. Fish tacos would’ve trended. Another entrepreneur would’ve seen how much surfers and travelers romanticized them, and beat him to it. Rubio’s success is in many things—the recipe, the people, a cleanliness not often seen in fast food (“Ralph is a clean freak,” says Robert), marketing, real estate, investors who believed in them (Union Bank, Rosewood Capital, Mill Road). But at least part of their success is because the pre-social-media age allowed fish tacos to remain largely unknown in the US until Ralph was ready to capitalize on them.

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

Rubio’s IPO in May 1999.

And boy, did he ever. The plan was always to make a scalable, quick-service restaurant model and replicate it. Ralph mentions McDonald’s as the ideal. Over four years, Rubio’s raised $9.6 million in capital and expanded to 63 locations. Fish tacos became San Diego’s most iconic food, as cheesesteaks are to Philly and pizza is to New York.

Since his first investors needed an exit strategy—and the tech boom had made IPOs the sexy business play in the late ’90s—Rubio’s went public in 1999. Buca di Beppo and P. F. Chang’s had recently done it and thrived. Ralph and his family flew to Rosewood Capital’s offices in San Francisco to watch Rubio’s enter the stock ticker. The IPO raised $23 million, allowing them to expand to 204 stores. It provided Ralph with lifelong financial security—and some grand delusions.

“The IPO was a massive thing—my wife, Dione, was there, my kids,” he remembers. “But looking back on it, it was a bad day in another way. I ran into this thing called ‘hubris’ and it knocked me on my ass. I got caught up in the fame and fortune and Rubio’s doing so well. I’m tracking my stock price. You can calculate your net worth every five minutes. I was foolish.”

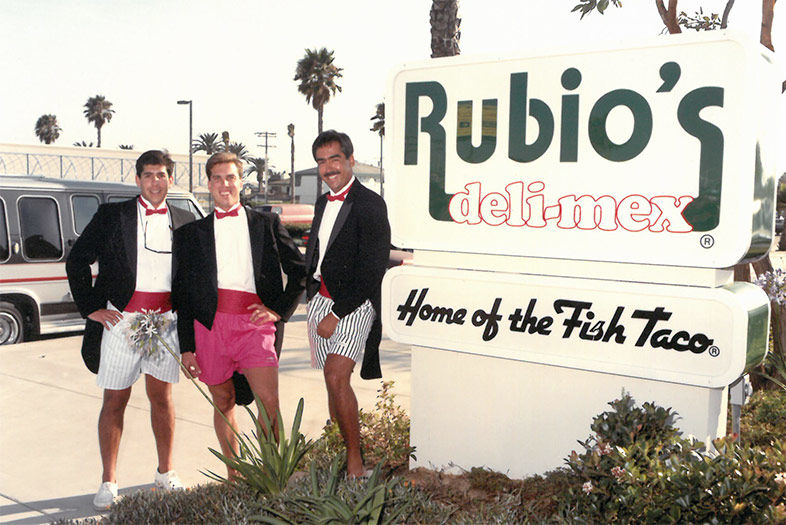

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

The grand opening of Rubio’s third location in Pacific Beach in 1986.

Changing Tides

The Rubios all liquidated their shares. Dad’s original $70,000 investment turned into a fairly massive number. Ralph was the last Rubio left standing when things got ugly in 2001. “We hit a wall,” he says. “After a year of underperformance, we had to close 11 restaurants. Harder, we had to let 100 team members go.”

They had grown too fast, venturing into markets they didn’t understand, making poor real estate decisions. Fish tacos sold better closer to the border, where Mexican food is familiar. Ralph even tried franchising, an idea he’d always disliked for quality control reasons. “When things are good, the relationship is great,” he says; “when things go bad, franchisees start cutting corners.”

His trusted friend Kyle Anderson, at Rosewood Capital, advised him to step down as CEO. “Those were dark times emotionally,” says Ralph, sitting in the backyard of his idyllic home in Rancho Santa Fe, which you must admit is a pretty safe place to admit past business faults. “I was full of too much pride. My feelings were hurt. I had some growing up to do. But it didn’t last long. I came around. One of the things that’s served me well is I’m very pragmatic. I was never trained to be the CEO of a publicly traded company. I had a good run.”

Ralph remained as chairman and cofounder, and worked alongside Mark Simon, who’s been CEO for eight years, “was trained to do this, and is a brilliant leader.” The company slowed its growth, massaged its marketing (they’ve gone through four name changes), and “operated our way out of it,” in Ralph’s words. In 2010, they sold for $91 million to Connecticut-based Mill Road Capital, which bought out the remaining public shares and made Rubio’s a private company once again.

Ralph is still a minority owner. He shows up every day, working closely with the culinary department. Half of his week is spent making unannounced visits to stores to inspect quality, to make sure they’re clean and customers look happy, to listen to the managers and inspire them, and to be the face of the brand.

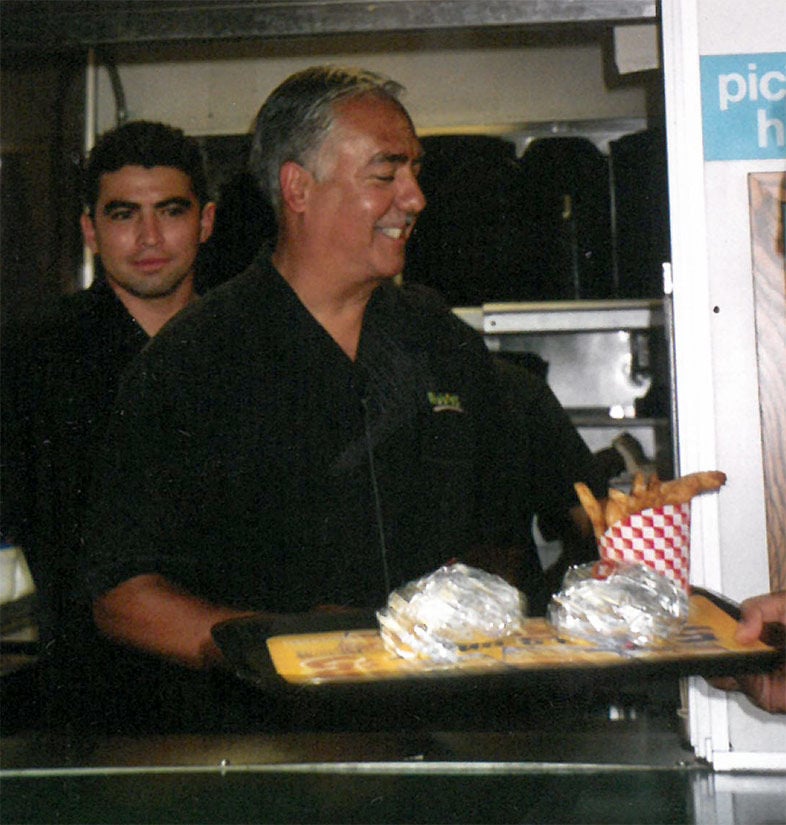

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

Ralph serving street tortas and fries at the Mission Bay location.

Rubio’s menu has grown to over 40 items. Though the wild Alaskan pollock fish tacos are still their biggest seller, bowls represent their biggest growth—many Americans have now learned that tortillas, while delicious, are about 270 calories a pop. Two trends in the US—increased seafood consumption, and the better-for-you food movement—are leading more and more customers their direction. In the test kitchen, we try a vegetarian, grainless version of a bestseller, the California Bowl. No one seems especially smitten with it. “This is just a disaster test,” Rubio says. “There’s enough promise there to keep working on it.”

In 2015, Consumer Reports asked over 32,000 readers to name their favorite Mexican fast food chain. Rubio’s came out on top, ahead of Chipotle and Taco Bell. In 2016, the city of San Diego declared April 5 “Ralph Rubio Day.”

“Awards are cool, but I’m just not into it, to be honest,” he says. “I love it more when I walk into a restaurant and they recognize me and say, ‘Hey, Mr. Rubio, I just want to say thank you. Me and my family come here every week.’ That’s what I live for.”

After opening their next location in Las Vegas (No. 196), they plan to pause growth and focus on operations at existing stores, making sure they’re solid. Eventually, Ralph thinks Rubio’s could open 400 stores in the western US. As a private company, they can wait until the timing is right, as opposed to when it’s necessary to meet quarterly forecasts. At some point, as dictated by life and age, the fish taco king will reduce his role—but not until he feels Rubio’s and “the people in the Rubio’s family” are set up for long-term success.

“I stayed for a couple reasons,” he says. “First, our name’s on the building. But really, I just love what I do. Not every day’s amazing, but I love getting up every day and going to work.”

As of print time, Rubio’s has sold 249 million fish tacos.

Ralph Rubio Is the Fish Taco King

PARTNER CONTENT

Photo by Nate Hoffman