Most people know how to taste a beer and talk about malt and hops; on the most basic level, the caramel aroma and the sweetness are from the malt, and the piney, citrus, grassy aromas and bitterness are from the hops. But very few people know that almost all the other aromas and flavor components in beer are actually created by something else: yeast.

Unlike the inanimate ingredients of water, hops, and malt—yeast are living things. [Yeast actually have their own order within the Fungus Kingdom—the order Saccharomycetales, which is a member of the phylum Ascomycota, to be exact.] Now, I’m no big science geek, but I do find the fact that beer is made with the help of living organisms to be truly cool. For those of you who aren’t completely sure how yeast works in the fermentation process, here’s the quick summary:

Yeast eat sugar. Beer is made by fermenting a sugar-rich liquid (wort; made with water, malts, and hops). Fermentation happens when the brewer adds yeast to the sugar-rich liquid and the yeast consume the sugar. As they metabolize the sugar, yeast excrete two key by-products: alcohol and carbon dioxide (the gas that creates the bubbles). Voila! Once the yeast are done gorging themselves on the sugar, the liquid has become a bubbly, alcoholic beverage that is more or less sweet, depending upon how much unconsumed sugar is left in the concentration. [Other compounds and components, such as esters, diacetyl, and fusel alcohol, are also created by yeast metabolism during the fermentation process. These also add to the overall character of the finished beer.]

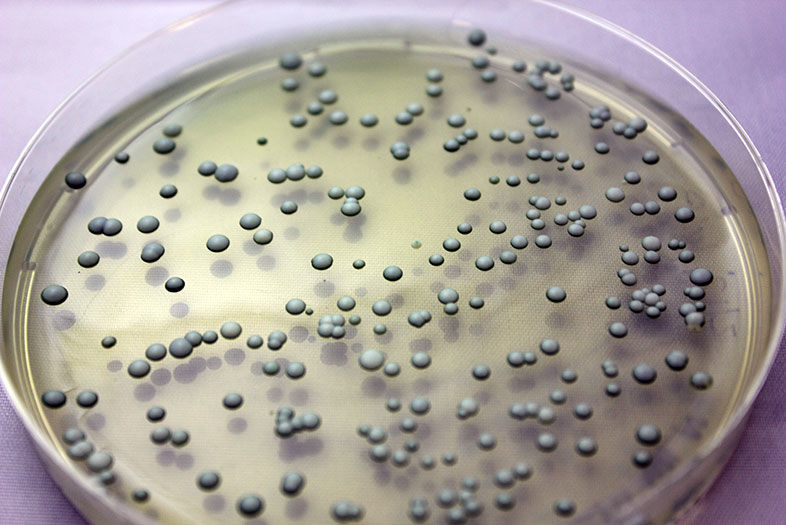

Now, if yeast’s role in the fermentation process weren’t cool enough, these little one-celled wonders also create a whole host of unique and highly desirable aromas and flavors in the beers they ferment. That banana and clove you detect in your Hefeweizen? That’s a by-product of the yeast. The bready, spicy, floral esters you love in your Belgian-style beers? Those are characteristic of Belgian yeast strains. The funky, earthy, barnyard-y stuff you smell and taste in brettanomyces beers? Brettanomyces is a kind of wild yeast that makes all that crazy-delicious stuff happen.

Brewers tend to know a lot about yeast, and San Diego brewers in particular are very fortunate to have one of the world’s largest and best-equipped yeast production facilities right in their own backyard. White Labs, located on Candida Street right off of Miramar Road, offers a whole host of yeast-related services, including a central location where San Diego brewers can pick up yeast directly from the source—that means they get it super-fresh, perfectly packed, and without the worries of long-distance shipping. It also means that a wide variety of yeast education resources are available to local brewers, many of whom choose to use White Labs as a brewing consultant as well as a go-to learning center.

There’s Actual Magic in Beer

Neva Parker, VP of Operations at White Labs. | Photo: Bruce Glassman

Neva Parker, VP of Operations for White Labs, has been in involved in educating brewers and the general public about yeast for many years. “There are still people out there who love beer who don’t even know that yeast is used in beer,” says Neva. “It’s not something people think about. And they don’t think about yeast providing anything to beer as far as the taste, the aroma, or the mouthfeel.”

White Labs provides numerous key services for brewers, and they help to train brewers in the critical process of proper yeast management. Many proprietary beer recipes rely on a very specific mix of water, grain varieties, hops varieties, and yeast strains—and once a recipe has established itself as central to a brewery’s success—brewers must manage their yeasts so they remain viable and will constantly produce consistent results from batch to batch.

The last thing a brewer wants is a beer that everyone loves, but no way to make it taste the same again! White Labs helps brewers by consulting on yeast usage, storage, and how yeast changes over time. Each time a batch of yeast is used (“pitched”) to ferment a tank of wort, the yeast reproduces as it gorges on the sugars. In some cases, depending on the conditions and how many times the batch has been used, the yeast will actually mutate as it reproduces.

“Sometimes these are mutations that people like and want to keep,” Neva explains, so White Labs provides the optimal storage to insure that a valuable strain remains healthy. In other cases, the company acts more as a simple storage facility. “Sometimes a brewer has acquired a strain through other sources, but they want us to grow it and keep it,” says Neva. “And other times, we’re just housing strains for people as a form of safe-keeping.”

Brewers often come to White Labs with a specific kind of beer they want to create—something with specific aromas and flavors—and the White Labs team will help to identify which yeast strains would work best. “That’s probably one of the most important things we do,” Neva says, “because there are so many choices out there now and, especially for a first-time brewer or a brewer who has never used our yeast before, those choices can be extremely overwhelming.”

There’s Actual Magic in Beer

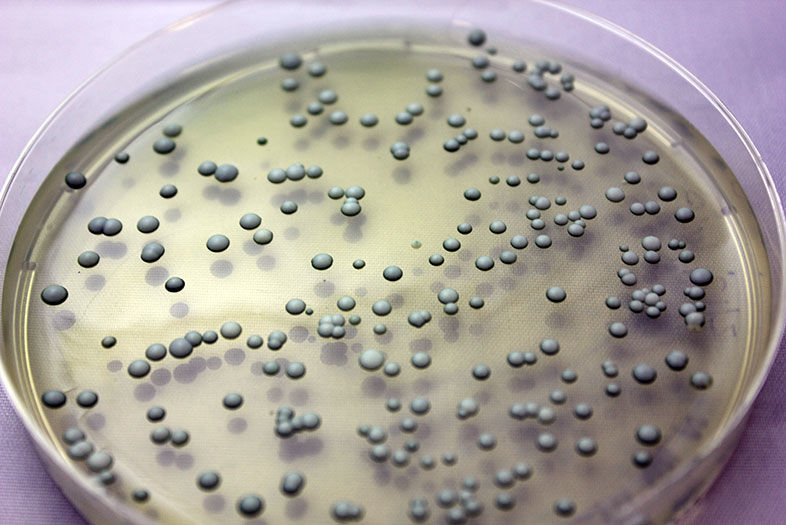

A yeast strain is tested for purity by a White Labs technician. | Photo by Bruce Glassman

Neva and her staff know the yeast strains they manage so well, they have actually observed specific “personalities” with certain strains. “There are some strains that we kind of joke about, just because of the way their slurrys are really flocculent, which means they’re really clumpy, like cottage cheese. Other strains, when we propagate them, they hold air inside and form these weird bubbles. Those are just specific behaviors you get to know about each strain.”

As a yeast producer and supplier, White Labs is actually on the front lines of beer innovation—based on what brewers are asking for, they see many of the newest trends as they’re taking hold—and way before the general public notices them. For example, White Labs witnessed the very beginnings of the sour beer craze and the brettanomyces craze.

Currently, they have seen a heavy increase in requests for New England style yeast strains, which produce the cloudy, hazy styles that have become all the rage. Most recently, White Labs has seen a spike in demand for “alternate strains” that can be used to make brett-style or lactobacillus-style (like Berliner Weiss) beers. According to Neva, these strains include “Sake strains and weird off-the-wall ones that people are asking about.”

If you’re interested in getting a more hands-on experience with yeast, you can visit the White Labs tasting room. There, you can get numerous “flights” of beer, each of which showcases the striking differences among a variety of worts fermented by a variety of yeasts. That unique San Diego beer experience is guaranteed to open your eyes to the wonders of yeast—especially in beer. Regardless of whether you visit or not, you should never sip another beer without thinking of those amazing little microscopic critters that made your delicious beverage possible.

There’s Actual Magic in Beer

PARTNER CONTENT

Brettanomyces yeast | Photo courtesy of White Labs