AjA Project.png

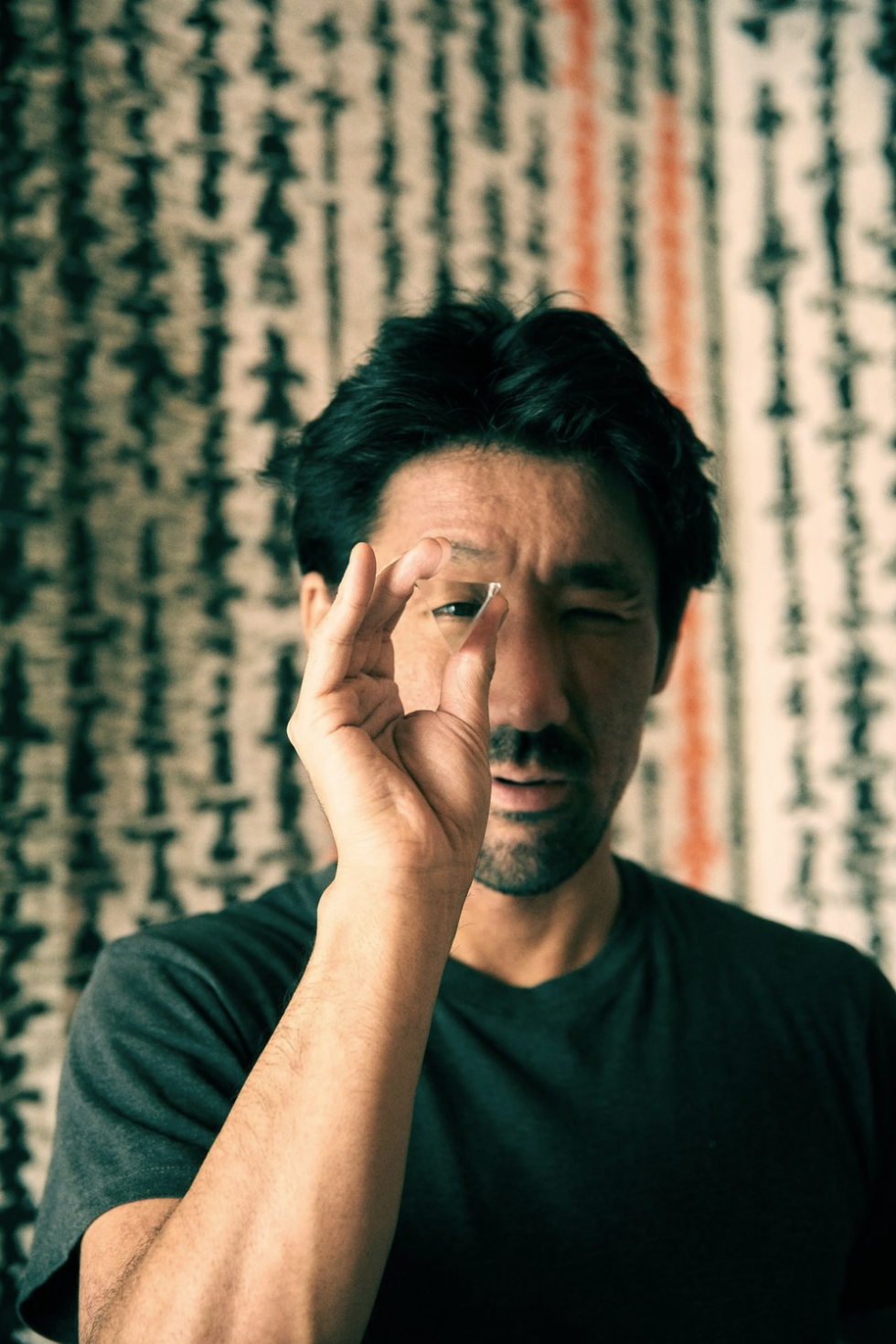

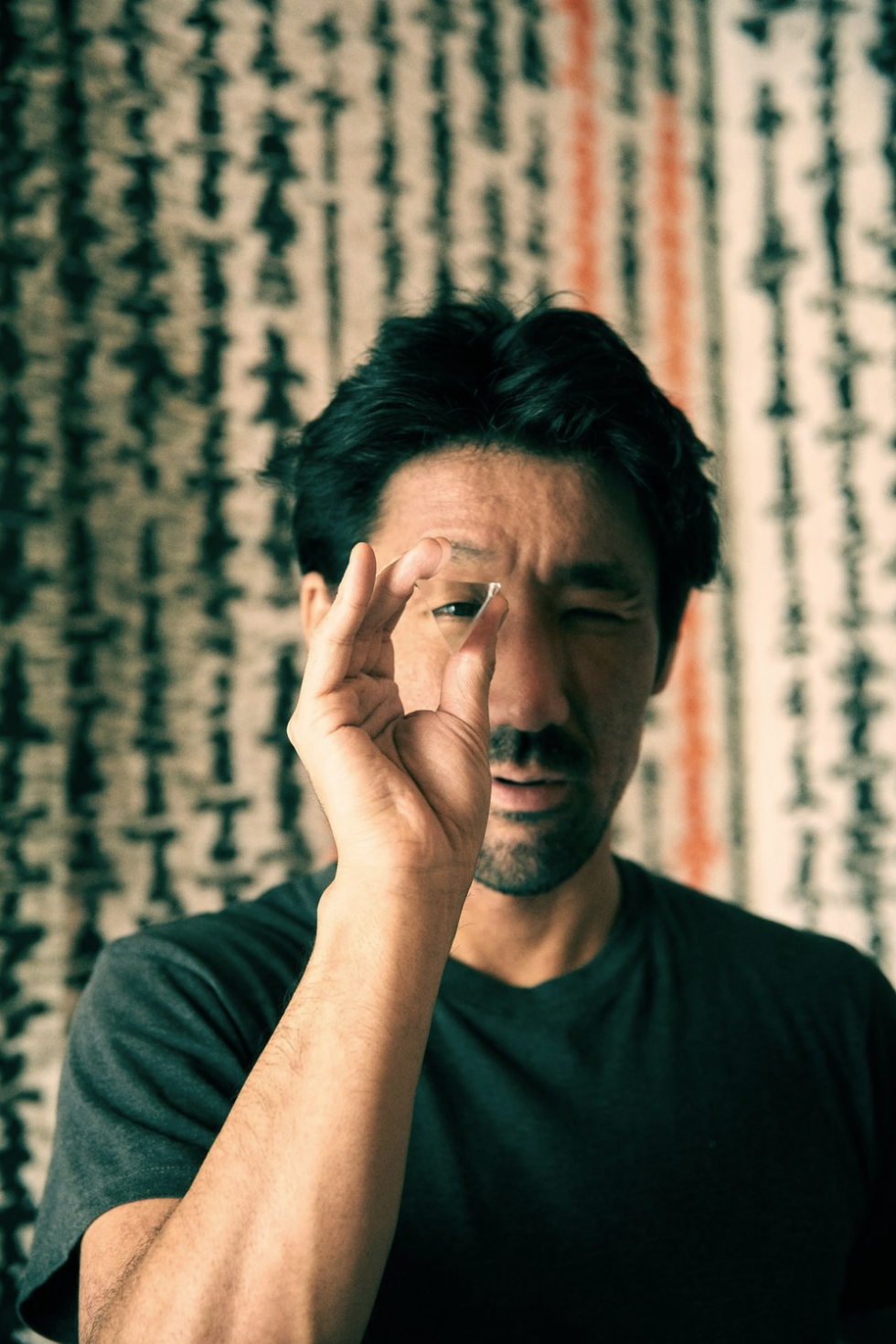

The AjA Project has humble beginnings. In the early aughts, artist and filmmaker Shinpei Takeda was working as a pedicab driver and funneling his take-home pay into his passion project: empowering refugee youth through photography. He and AjA Project cofounder Warren Ogden were able to set up shop in an Ocean Beach home, using the living room as an office and the garage as a darkroom. The fledgling nonprofit secured a donation of 50 cameras and darkroom equipment and began working with refugee populations in El Cajon and City Heights.

“There are many young people that were refugees from countries like Somalia, Afghanistan, and so on,” Takeda says. “We would give them cameras, teach photography—back then it was still black-and-white cameras—and we would develop it on our own. They would learn how to tell stories, how to find your voice, how to use your voice, and how to raise your voice. That kind of became our motto a little bit later as the project became bigger and bigger.”

When the AjA Project started, it was a different time, Takeda recalls. The country was still reeling from the September 11th attacks and many people were unaware of the issues refugees face.

“I felt that their point of view was always missing in the narrative,” he says.

The AjA Project hung prints with each photographer’s story around City Heights and hosted public art exhibitions in an effort to ease tension and build community. They later moved to a larger space, a former library building. Takeda and team began reaching out to the neighborhood’s underserved youth and immigrant populations, creating a safe space for self-expression in more than just photography and exploring issues like civil rights and police surveillance.

“We try to make this as a platform for people without opportunities to be able to come and find their voice through storytelling and through photography and documentary arts,” he says.

Takeda says he’s humbled that the project has impacted so many people. He’s also been spending time looking through old photos and reflecting on the past 23 years as the AjA Project gets ready to move to a new location.

PARTNER CONTENT

“These histories aren’t archived in official institutions,” he says. “I would like to make sure that these histories are saved and shared for future purposes so that we don’t make the same mistakes. I’m also trying to raise questions, and I think there are some things we can do. I’m excited about where we will go next.”