Health care professionals are among the world’s hardest workers. They persevere through 12-hour shifts, sometimes longer, most often on their feet; they suit up in protective gear to tend to patients battling infectious diseases; they comfort families facing loss, and they calm combative patients and visitors. They face death and go home mentally and physically drained. It’s enough to weigh on anyone. Yet doctors, nurses, techs, and countless other health care professionals keep going in to work every day—even when a pandemic has shut down much of the world and transformed life as we know it.

April Moon Waara

Jenny Siegwart

“This is a very stressful time for our health care teams,” says April Moon Waara, chief clinical operations officer for Sharp Rees-Stealy. “Individuals have increased anxiety due to the pandemic, and specific stress associated with providing direct patient care to those with symptoms and those diagnosed with COVID-19. There have been several recent studies on the impact of pandemics on health professionals, and there is a high prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Insomnia, burnout, emotional exhaustion, or somatic symptoms were also reported. The additional strain of frequently changing national, state, and local guidelines and directives increases the stress placed upon health care professionals, especially if systems are not prepared to respond to pandemics that may last several months or years.”

To help these professionals during this challenging time, health care systems across the country have increased their workers’ access to emotional support programs and implemented robust telehealth systems, allowing staff the flexibility of working remotely and allowing patients to access care from home.

Waara explains that the effect of telehealth is threefold: “First, removing non-direct patient care roles from the clinical setting reduces the opportunity of exposure. Second, it supports social distancing. Third, it can create additional capacity by offering nontraditional clinics and virtual hours to patients.”

While it may have taken a pandemic for popular consciousness to recognize them as “essential,” those who work in the field know that they face challenges 365 days a year—in normal times or otherwise. These are some of the additional ways that local health care organizations are working year-round to reduce some of the stressors faced by their staff.

ICU RN and ECMO specialist, Tige R. Leivas, at Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center

Angela Klinkhamer

Protecting Against Workplace Violence

We are all aware of the contagions these workers face on the job. But a lesser-known threat puts their lives in even more immediate danger: violence committed against them in the workplace. In fact, they are the population at greatest risk of suffering assault or injury on the job. A 2018 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that health care professionals accounted for 73 percent of all nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses due to violence that year. A multitude of factors contribute to this risk—caring for patients with mental illness or drug addiction, environmental factors, staffing shortages—so the challenge is significant, and the solutions are multifaceted.

Mary Prehoden, a nursing supervisor at Scripps Mercy San Diego who was attacked by a patient there in 2018, emphasizes that this problem needs addressing at a foundational level.

“Violence against nurses has continued to rise over the past several years,” she says. “The reasons are multifactorial. First, nurses spend the most amount of time with patients and come in the closest direct contact. This alone, unfortunately, makes us greater targets for a patient’s violent verbal and physical outbursts.

Mary Prehoden

“Urban hospitals like Scripps Mercy treat high numbers of individuals with untreated or undertreated mental illnesses, and drug and alcohol abuse. We attempt to provide care to these volatile patients with minimal physical restraints. The assaults perpetrated by patients run from verbal berating to egregious physical assault by punching, kicking, biting, spitting, and using medical equipment at hand against persons who are just trying to provide care. This constant barrage not only takes a physical toll, but the mental aftereffects are lifelong and sometimes career changing, or career ending.”

Along with many other nationwide efforts by leading organizations like the American Nurses Association and The Joint Commission, Scripps Health is taking steps to mitigate risks and protect workers from violence in the workplace.

“Scripps has made some headway in early identification of patients who could be high risk for violence,” Prehoden says. “We have visual cues outside patient rooms, as well as arm bands that all staff have been educated on. We have also created a rapid-response team that includes nurses and security to intervene with patients before they fully escalate into harming staff or themselves. De-escalation training is offered for all staff, where in the past it was mandated only for the emergency department and behavioral health staff.

“There is no magic answer for this problem. We must work together with other health care institutions and share best practices in the care of these patients and in staff safety. Our communities cannot afford to keep losing nurses to assaults. This hurts everyone who needs the skilled care that we provide.”

Shining a Light on Suicide Risk

Morethan 800,000 people die by suicide each year—and health care professionals represent a disproportionately high percentage of them. In fact, according to a study out of UC San Diego, female nurses die by suicide 58 percent more often than the general population; male nurses, 41 percent more often.

Judy Davidson

“Given these findings, suicide prevention programs are needed,” says researcher and nurse scientist Judy Davidson. Her organization, UCSD Health Sciences, created the Healer Education Assessment and Referral (HEAR) program, a simple, anonymous online screening assessment to help identify health care professionals who are in crisis.

Now in its fourth year of operation for nurses and 11th year for physicians, HEAR is being replicated in organizations across the country. Davidson says that now is the time for all health systems to take action, since pandemics are known to increase the prevalence of mental health issues and rate of suicide among health care workers.

“HEAR works to identify clinicians at risk and move them into treatment,” she says. “Through a simple email that invites clinicians to do a risk screening, we are finding approximately 40 nurses a year in one organization that need help—many of them expressing suicidal thoughts—and referring them into treatment. They are there, just under the surface, waiting for someone to reach out to them. Our prevention program has raised awareness and done a lot to reduce the stigma associated with getting help, and our clinicians now actively recognize colleagues in trouble.”

Helping the New Workforce Grow and Thrive

The sentiment that “nurses eat their young” expresses a common fear among nursing students about to enter the workforce, referring to the nursing shortage that has existed for at least the last decade. But workforce development efforts are consistently put in place to debunk this myth and support new health care professionals as they begin their career path.

One such effort is the New Graduate Nurse Residency Program at Sharp HealthCare, which provides a flexible, supportive environment to help nurses build confidence and thrive in their new roles. The program pairs new grads with preceptors for 12 weeks on various units to help them acclimate.

Sara Wren

“By having consistency of leadership, interdisciplinary involvement, and peer support, the residents demonstrate a stronger leadership role at the bedside,” explains Sara Wren, a nursing workforce professional development specialist at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center. “The collaboration allows the new grad to have multiple resources to develop their clinical decisions for the patient. As the new grad is sharpening their bedside skills, they are learning prioritization, delegation, and collaboration both at the bedside and in the classroom setting.”

A year later, the new grad meets with a mentor through Sharp’s CareForYou program.

“This allows the resident and the mentor to talk openly and develop a goal,” Wren says. “It also allows time off the unit with a trained peer supporter as immediately as possible to debrief after an event occurs. The residents that participate in this program find the transition during the first year of nursing not as challenging.”

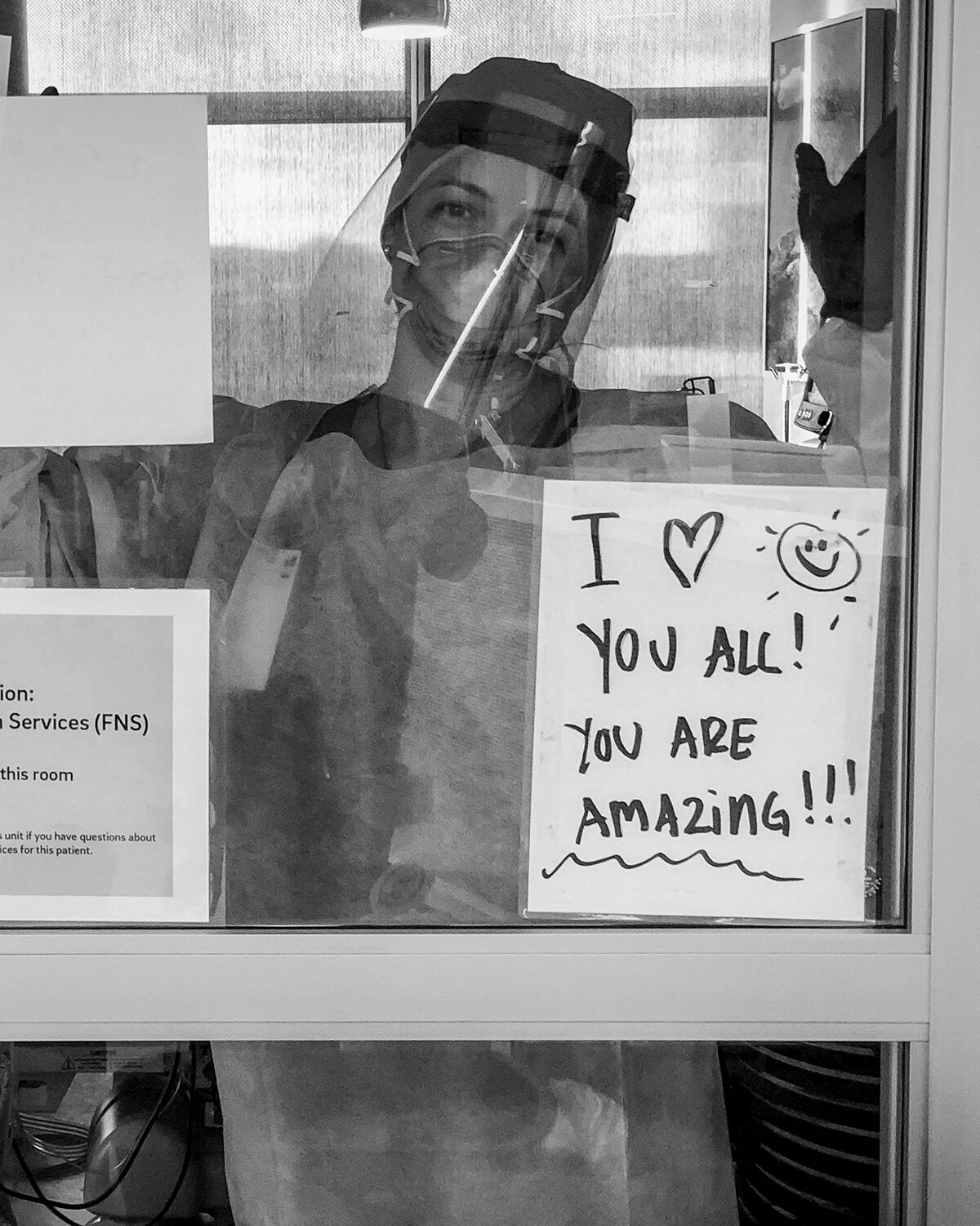

ICU nurse Rachael Stokes sends a message at Jacobs Medical Center. These black-and-white photos were captured by ICU nurse Angela Klinkhamer to document their experiences during the early days of the pandemic.

Angela Klinkhamer

Providing Peer-to-Peer Support

Compassion. Peace. Renewal. Three things we could all use in our daily lives—perhaps no one more than the pediatric nurses at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego.

JoAnne Auger

JoAnne Auger, a supportive care registered nurse coordinator at Rady Children’s, created Compassion, Peace, and Renewal (“CPR”) for the Soul, a program designed for nurses working with children with life-threatening illnesses.

“Working with sick children is a paradox—it drains you but it fills you up,” Auger says.

CPR for the Soul is designed to create a caring infrastructure for health care teams who face the difficult, demanding, and emotionally charged work of caring for seriously ill children. The program’s sessions serve as a time for the staff to pause, breathe, and rebalance; it includes guided meditation, journaling, and a safe space to share on-the-job challenges, as well as four-hour retreats that incorporate further self-care.

“As nurses, we often put our self-care needs down at the bottom of our priority list,” Auger says. “CPR for the Soul provides a space to share the difficult work, debrief from the challenges of the day, and talk about our own struggles. We need to take care of each other to be there to take care of the kids.”

ICU RNs and ECMO specialists, Tamara Norton and Joanna Lung, at Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center

PARTNER CONTENT

Angela Klinkhamer