San Diego’s epic, photogenic bridge was nearly an eyesore.

If earlier developers had succeeded, the Coronado Bridge would’ve been a mass of chunky, criss-crossed trusses and trestles jutting into our view of San Diego Bay, scarring the skyline with industrial steel. But serendipitous delays (and firm resistance from a local architect) changed the plans.

The idea for a vehicle crossing to Coronado goes back to 1926, when magnate John D. Spreckels proposed a bridge to ease travel to his money-making properties. The War Department shot it down, citing possible interruption to naval activities. In 1928, developers obtained permits for a subaqueous tube; the Depression kept that at bay. The Coronado City Council floated the bridge idea again in 1935. Once more, Navy opposition promptly sunk it. Would it block ships sailing out to sea from South Bay? Would it collapse in an earthquake and strand the fleet? An admiral testified that Navy dollars would cease to flow into San Diego if the bridge came to pass.

The State of California revived the Coronado crossing idea in 1955. Bridges for autos were going up all over the state. The Navy finally got on board, with the deal-clincher that the bridge’s height allowed enough vertical clearance for aircraft carriers. The USS Midway, the tallest carrier at the time, was 222 feet from keel to highest point. To meet the height requirement, bridge designers eventually devised the now-famous curve—worked out one afternoon with a few pushpins and a piece of string. But as the bridge concept took its first steps forward in decades, its now-award-winning design was still a twinkle in an architect’s eye.

The state’s architectural plans from 1957 show harsh-angled beams and legs marring the Coronado crossing, out of place against the gently sloping shoreline and gentle waves of the bay. Coronado residents balked, bringing lawsuits as the possibility of a bridge became concrete. It threatened the peninsula’s scenic beauty and tranquil quality of life. On the San Diego side, the planned bridge landing cut through historic Barrio Logan.

James R. Mills, San Diego representative from 1960 to 1982, opposed the bridge on behalf of his townsfolk. “Like me, most of them wanted their town to stay as it was, and they loved the ferry boats, which had been running to and fro across the bay since 1886,” Mills wrote in a 2009 op-ed.

In 1961, Mills voted “no” on a state budget that “surreptitiously” slipped in a bond measure to finance the bridge. On the day of the decision, “people were scurrying around the floor handing out envelopes with thousands of dollars of cash to those who would vote for it,” Senator Mills later told his friend, Coronado author and historian Joe Ditler.

Those greenbacks likely came from John Alessio (the “A” in Mister A’s), Hotel del Coronado owner and big-money contributor to California Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown.

“‘John Alessio wants that bridge. He bought the Hotel del Coronado with the land south of it so he could make a lot of money by selling that vacant land for a high-rise residential development, and that will only happen if a bridge is built,’” a colleague told Mills, as Mills later recalled in the op-ed. “[And] if John wants that bridge, Pat [Brown] wants it.’” It passed by one vote.

Though resistance couldn’t stop the bridge, delays worked out in San Diego’s favor. Coincidentally, a few years prior to the bridge’s green-lighting, Governor Brown had instituted a new program: Every state bridge project would have an architect consultant to ensure “no more ugly bridges”—his response to Bay area residents who objected to the industrial-looking Richmond—San Rafael Bridge in 1956. The Coronado Bridge was the second built under this mandate.

Yet even the bridge’s designer, local architect Robert Mosher, initially called the idea “nuts.” Mosher (who studied with Frank Lloyd Wright and founded San Diego’s oldest architectural firm, Mosher Drew) worried about “ruining” Coronado Island. Nevertheless, Mosher’s longtime colleague Larry Hoeksema told SDM, he accepted the job and made every effort to “take care of all the aesthetic components: the color, the curve, the arches, the graceful line.”

When Mosher came aboard in the mid-1960s, the open-trestle design from 1957 was still the top contender. “The design was strikingly similar to that of the hated San Rafael– Richmond Bridge,” Mosher reflected in his writings.

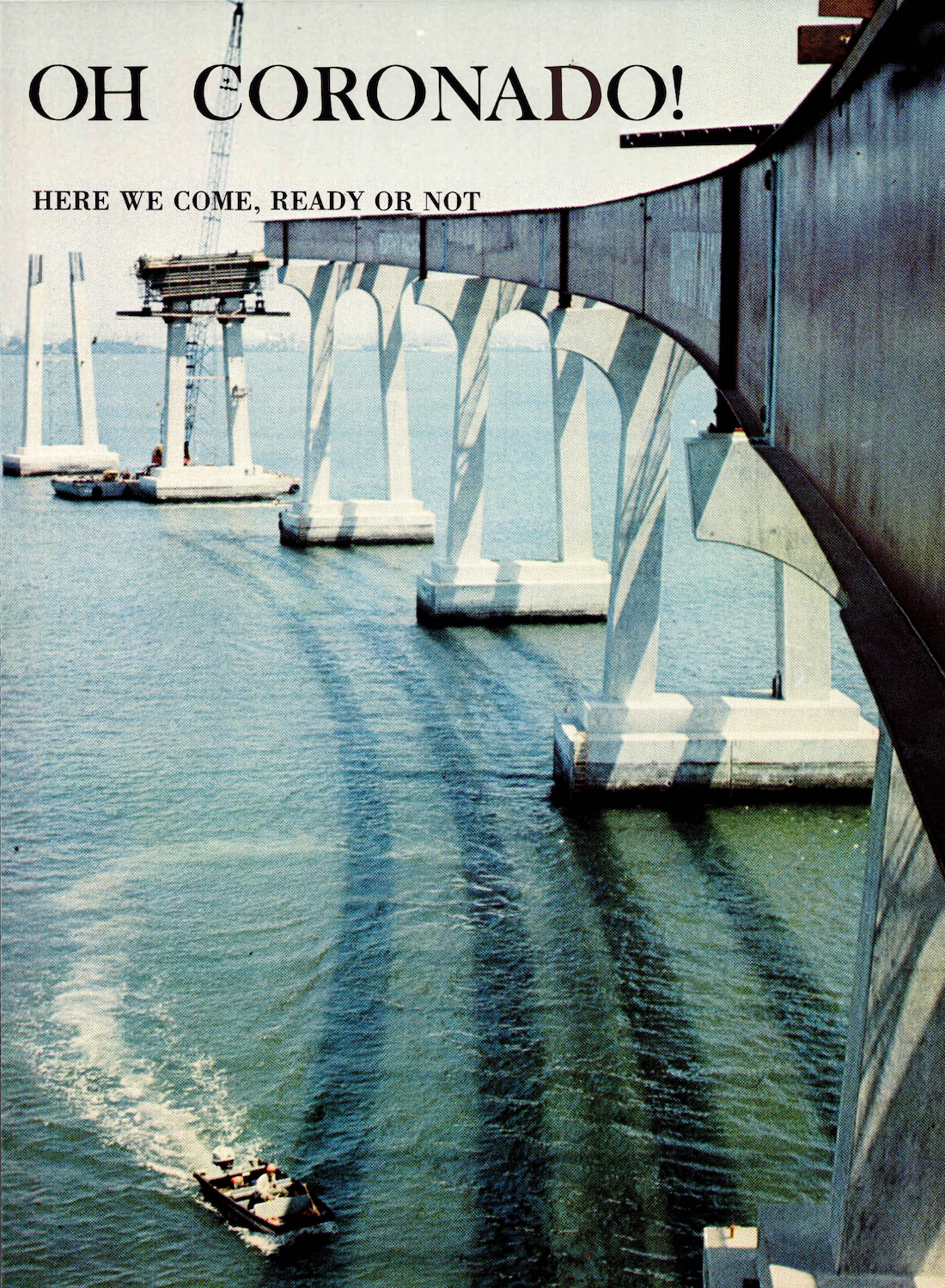

So Mosher and a team of state engineers came up with a new proposal: closed box girders (horizontal support beams tucked under the bridge) for a neater look and a new, German-patented orthotropic design to eliminate towering trusses. Mosher added graceful arches below to echo San Diego’s mission-style architecture. The sides were purposely low to give drivers the best view. Then came the curve.

But Mosher’s ribbon-esque, elegant new design wasn’t a shoo-in. The plans came within inches of rejection by the state committee for “budget concerns.” As Mosher tells it, he threatened to alert the press (he had friends at both the Union and San Diego Magazine) that the state—contrary to the governor’s promise—had doomed San Diego to an unattractive bridge. The state opted to save face; Mosher’s team found ways to meet that budget.

“Instead of just a crossing, we wanted to make the event of crossing enjoyable,” Mosher told a reporter following the design’s public unveiling. “Going across the bridge will be equally as interesting in its 20th-century way as the ferry is. It’s going to be fun.”

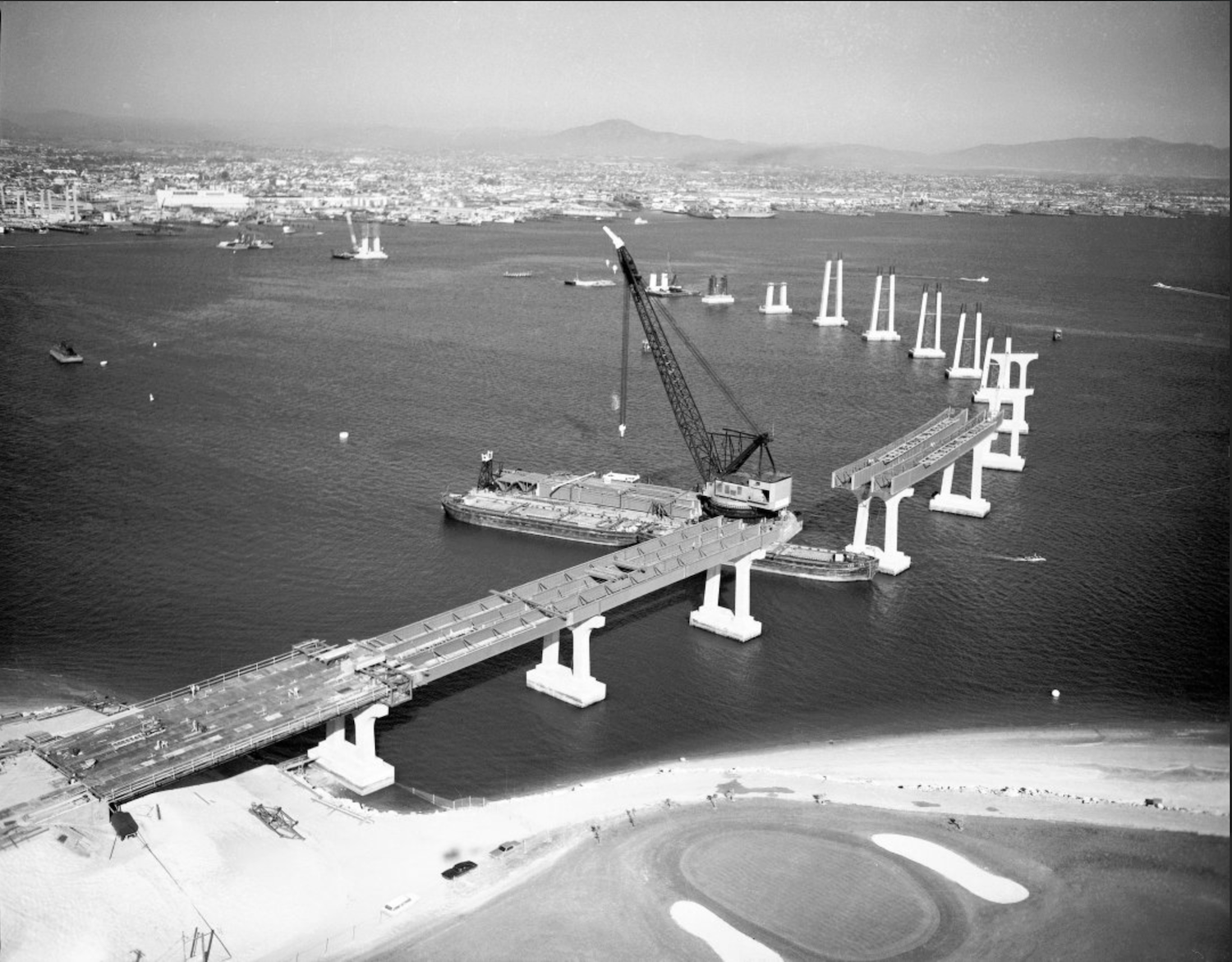

Construction finally began in 1967, with a price tag of $45 million (almost $450 million in 2025 dollars). Workers drove 487 concrete piles 100 feet into the mucky bottom of the bay and put up 30 arches. The 215-ton steel box girders were fabricated in San Francisco, shipped to San Diego, and hoisted into place with a barge-mounted crane. All told, building the bridge took two years; 94,000 cubic yards of concrete; 20,000 tons of steel; and 43,000 gallons of paint.

Mosher had to fight for his finishing touch, too: the distinct blue paint that blends hues from the sky and bay. Rust-proof red was the default for bridges over water, Hoeksema says, but Mosher reminded the team that “ugly” was not an option.

Historian Ditler moved to Coronado in 1967, as a teenager, and watched the bridge take shape. He and his buddies “thought the whole thing was ridiculous,” he says.

PARTNER CONTENT

At the time the bridge was built, red was the standard for crossings over water, but architect Robert Mosher fought for serene, coastal blue.

That didn’t stop them from riding the last midnight ferry (service ceased from 1969 to 1986) and being “the first hitchhikers,” he adds, to cross the new bridge when it opened on August 2, 1969.

In the back of an MG with a happily stoned couple in the front, “we sat on the convertible top that had been folded over the back seat,” he recalls. “Like being in a parade, we drove over that big, scary bridge, waving at everyone we saw.”