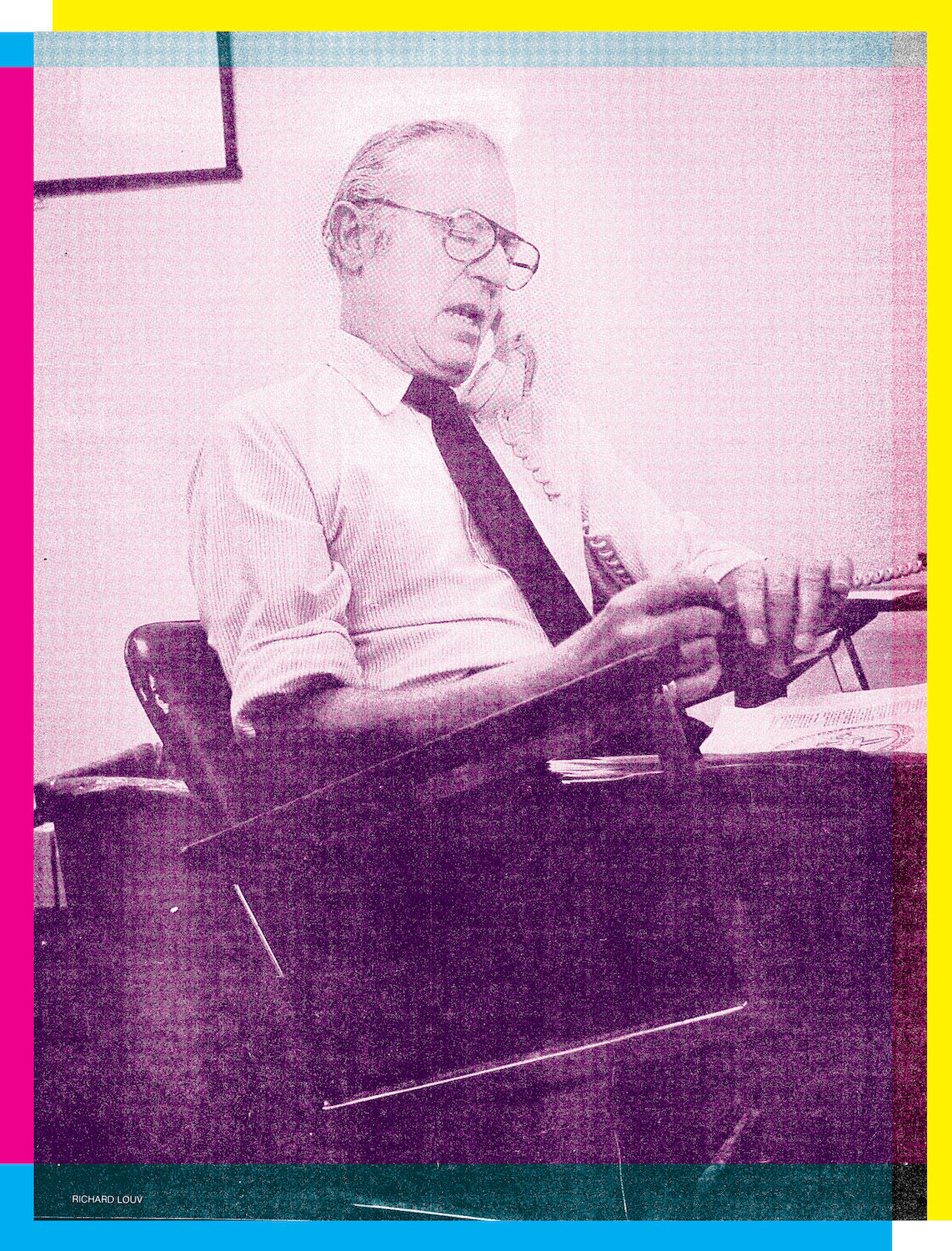

According to San Diego Magazine’s obituary for Keen (1981), SDM printed more than half a million of his words over the course of his nearly 20-year career. Here, he’s shown preparing for his TV show, Telepulse, in his KFMB office.

He got choked unconscious in a wrestling ring. He subjected himself to a mock trial for littering. Rather than stand on the sidelines and observe, Harold Keen threw himself headfirst into the action.

Like the time he stripped his clothes off while reporting on a nudist colony. “It’s a part of the whole titillation process,” he joked, later remarking that the people who remained dressed were the most conspicuous and uncomfortable.

That was on television, for KFMB. In print, Keen proved to be a very different kind of correspondent, but his belief that immersion was the key to understanding unfamiliar worlds never wavered.

December 1964 San Diego Magazine Headline Harold Keen

August 1966 San Diego Magazine Headline Harold Keen

In his 20 years at San Diego Magazine, Keen wrote about politics and the persecuted, with a steadfast devotion to the underdog. In December of 1964, he produced a sympathetic profile titled “Why CORE Breaks the Law.” In it, he centered Black activists and their white supporters at the Congress on Racial Equality, who were vilified for leading protests over racially discriminatory hiring practices at Bank of America.

Print gave Keen the opportunity to unpack complex topics in a way that he never could on television. He wrote at length about de-facto segregation, giving space to people who compared San Diego to the backwoods of Mississippi and noting himself that, even though racial imbalance was against public policy, city schools here were statistically less integrated than those in Little Rock, AR. Keen stood virtually alone in local media when he came to the defense of UC San Diego professor Herbert Marcuse, a Marxist philosopher who’d been targeted by politicians, daily newspapers, and—as we now know—the FBI. Keen called the campaign to oust Marcuse a “self-appointed form of vigilantism.”

March 1962 San Diego Magazine Headline Harold Keen

January 1974 San Diego Magazine Headline Harold Keen

Re-reading his long-form pieces today, one gets a sense of how little has changed. Another of his favorite topics during the Civil Rights era was the rising influence of the radical right, which included the John Birch Society and other anti-communist groups. They were convinced that a conspiracy was afoot to undermine white, Christian values in schools and subvert the republic with fair housing laws, urban planning, and fluoride.

Change a few details and those articles could be written now about the hysteria over critical race theory or gender-inclusive bathrooms. Keen may have listened to all sides, and quoted them fully, but he also provided crucial context and weaved his own personal reflections into otherwise faithful accounts of the arguments going back and forth at the time. “This has been challenged by the ultra conservatives, who refute the claim of objectivity with their own standards of truth,” he wrote in March of 1962.

By the 1970s, Keen had refocused his attention on the city’s industrial, financial, and real estate elite whose interests governed the political class. He patiently explained to readers who the power brokers were and what they wanted. That included a 31-year-old Doug Manchester, who would go on to become the publisher of the San Diego Union-Tribune and to financially back Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. A new breed of titans ruled the territory, and, Keen revealed, their influence was diffuse.

Towards the end of his life, Keen’s composition became livelier, more sarcastic, and more deductive.

“With large open spaces yet to be developed in one of the world’s most attractive places to live, San Diego County will increasingly feel the conflicting pressures of environmentalists and the money movers who must find an outlet for their vast resources,” he wrote in January of 1974.

Keen, who was known as the “Dean of San Diego Journalism,” is shown in his home office, surrounded by awards he’d won throughout the years. Look closely and you’ll spot his prosthetic leg perched beside him.

The effect of this tension can still be seen in almost any land-use dispute over urban development and sprawl—perhaps most notably in a 2020 ballot measure that attempted to put restraints on home construction in rural and semi-rural areas.

It’s no coincidence that Keen was nearly 50-years-old by the time he started writing for the magazine. He brought with him decades of institutional knowledge and worked an insane schedule for any age. His relentless output likely contributed to his three heart attacks and the amputation of his left leg in 1975 due to circulatory problems. His byline continued to appear in the magazine after his death in June of 1981.

PARTNER CONTENT

Keen didn’t break any Watergate-style corruption on his watch, but his analysis served as a roadmap to help others make sense of scandal when it did arise. He’s rightly revered today as San Diego’s sociopolitical historian—a reporter who took the long view and teased out the city’s theme-park logic, not in academic jargon, but with the voices of ordinary and powerful people alike.

Journalists like to think of their work as the first draft of history. In Keen’s case, that was actually true.