Chino Farm has one single, overarching priority: They grow for flavor, of which beauty is a natural byproduct. On a pristine 52-acre plot (45 are cultivated) in the middle of Rancho Santa Fe, the Chino family has quietly pioneered specialty farming in America since the 1970s.

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

I get a little shiver rounding the bend toward The Vegetable Shop at Chino Farm in Rancho Santa Fe. From the street, the farmstand looks like a weather-beaten shack. But stepping inside reveals a kaleidoscopic array of just- picked heirloom produce where everything tastes like the heightened, ultimate version of itself. Alice Waters—the Bay Area doyenne of cooking with local, seasonal, and organic produce—has called Chino “the most important farm in the country.” Whenever I visit, the stand feels like one of the culinary wonders of the world.

Arriving at sunrise, I am greeted by Tom Chino, the soft-spoken manager and the youngest of nine siblings born and raised on this family farm. As we shake hands, I feel all 70 years of fieldwork etched into his palms.

Tom Chino reviews the day’s tasks with his crew, most of whom have been working with him for more than 20 years

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

“Not much going on today,” he tells me. “You’ll probably get bored.”

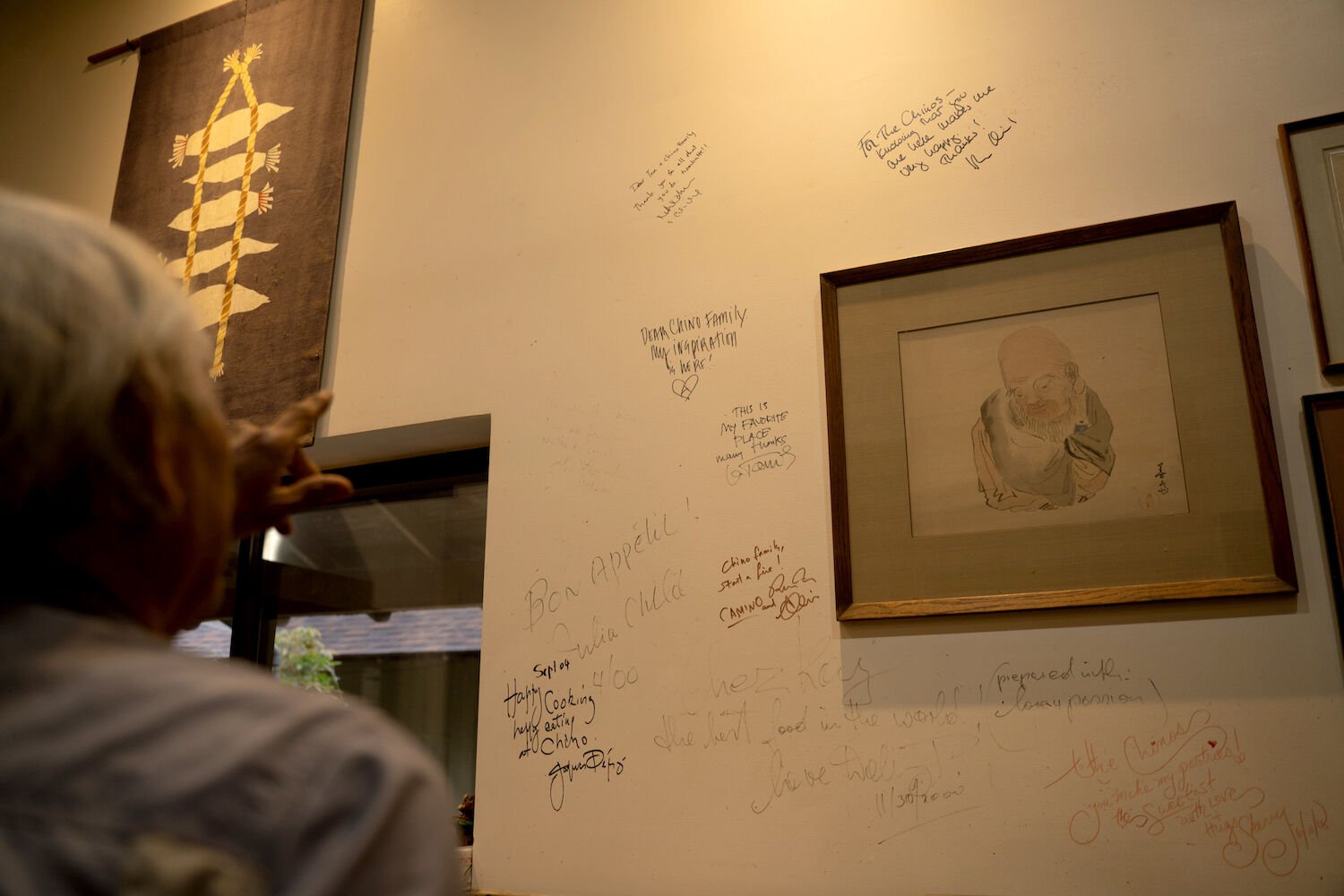

Tom leads me behind the farmstand to the family compound. Shoes come off at the door to the kitchen, where he brews a pot of coffee for his crew. On the wall above the kettle, I glimpse a pantheon of my culinary heroes: Jacques Pépin, Julia Child, Alice Waters, and Yotam Ottolenghi (among others) have scribbled their homages to the Chino family in permanent marker.

This will be the only outward sign I see of the rockstar status the farm has earned in the food world, and of the impact they have had on inspiring and modeling small-scale specialty farming in America. Tom only hints at this legacy when I ask what produce Alice Waters still buys for her restaurant in Berkeley. “She’s a great friend,” he says, “but now she can get everything she needs from farms in the Bay Area.”

Tom offers the first blackberry of the season

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

Tom motions me to follow him to a Shinto shrine in the far corner of the room. It’s decorated with photos of his parents, who immigrated from Japan in 1920 and founded the farm in Rancho Santa Fe after first losing everything when they were forcibly relocated to a Japanese internment camp during World War II. Grit and self-reliance are written into the family DNA.

Tom lights incense, rings a singing bowl, and bows in prayer. He gestures for me to do the same. We put our shoes back on, and the day’s work begins.Tom brings coffee to his field hands and delivers a summary of the day’s harvest and planting goals. The team disperses in beat-up pickups with their assignments. When I remark that it’s incredible that all 45 acres of crops are tended by Tom and six other men mostly in their 60s, Tom reminisces.

Chino Farm’ “wall of fame” features heartfelt messages from some of the culinary world’s biggest names

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

“We used to have 10 to 15 full-time workers, and then another 10 apprentices from Japan at any given time,” he says. “Covid killed the internship program, and no field hand can make rent within an hour of this farm.”As a result, he continues, “We’re not producing the variety that we used to. This year we’re only growing 80 varieties of tomato, down from 120.” Tom’s pained expression reveals his disappointment. Perhaps he worries he is somehow letting his parents down.

After WWII, Tom’s folks were determined to build a “real farm,” which, at the time, meant growing a handful of crops in large volumes to sell to wholesale distributors. As it became clear that their 45 acres of produce could not compete with massive commercial operations, they experimented with a farmstand model in 1969, selling corn and tomatoes to locals. It clicked.

Junzo and Hatsuyo Chino founded their farm in what was then a rural expanseof fields near Del Mar in the late 1940s. They raised nine children on the property. Today three of their sons, including the youngest, Tom (pictured right), continue their agrarian legacy.

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

Tom worked at the farm from childhood through college, but when his parents fell ill a few years later, he cut short a promising career as a biotech researcher at the Salk Institute to return to the farm full-time. He doubled down on their farmstand vision by experimenting with a dazzling variety of produce and modernizing some farm practices.

After a little prodding, he tells me that one of his innovations was calculating the “sun hours” that each vegetable needed to ripen so he can tell—practically to the day—when a crop will be ready. (Chino Farm is never short on sweet corn for the 4th of July weekend.) Tom is equal parts researcher and tinkerer, and he finds joy in constantly experimenting with new seeds.

During the height of summer, the field crew works seven days a week, while the farmstand only opens for five. There are two days without harvest to give the crops a chance to ripen for the next week.

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

“The thing that really matters is that we grow for flavor above all else,” he says. I watch two field hands walk rows of heirloom cucumbers and summer squash, picking the vegetables when they are much smaller and more tender than what I’m accustomed to buying off grocery shelves. Tomatoes and strawberries are plucked only when they are practically bursting at the seams with natural sugar. Afterall, the produce harvested here must only withstand the hundred-yard trip from field to farmstand, not a thousand miles under refrigeration.

Small wonder the Chinos are so revered by great chefs—they grow the kind of food that’s worth a special journey.

A dense carpet of weeds is left intact to help the soil retain moisture, but they can make harvest slow-going

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

Tom Chino. Farmer, savant, dutiful son.

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

Chino Farms Rancho Santa Fe San Diego 2023 Vegetable Shop

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

This farmstand salad features Chino’s bitter greens, edible succulents, guava flowers, and strawberries, plus a creamy herb vinaigrette

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger

PARTNER CONTENT

Greens fill the original Chino Farm produce box alongside their famed Mara du Bois strawberries

Photo Credit: Eric Wolfinger