Heart Disease | Medicaid Cuts | Cancer Treatments | Artificial Intelligence

Heart Disease Treatment & Prevention Questions

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the US. Scripps Clinic electrophysiologist Dr. Doug Gibson; Kaiser Permanente cardiologist Dr. Bahram Khadivi; and Dr. Jia Shen, cardiologist and director of the Bankers Hill cardiovascular clinic at UC San Diego Health, weigh in on why—and what advancements might help change that stat.

Why is heart disease so prevalent in America today?

Dr. Doug Gibson: The simplest way to think about it is that, for most of modern human history, we haven’t had easy access to unlimited resources such as food, [and] we had to expend more physical energy to acquire these resources. We got more exercise, and we didn’t have processed foods at the convenience store down on the corner. Modern human genetics are largely the result of that scarcity that we all lived through as human beings over the last 500 years. These genetics don’t do well with easy access to unlimited resources and lack of exercise. The end result is that, because of the agricultural and industrial revolutions, humans have had to expend less effort to acquire resources such as food. This has resulted in more risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity.

Generally, cardiologists will advise patients at risk for heart disease to achieve or maintain a healthy weight. GLP-1 or semaglutide medications have made the news in recent years as a revolutionary weight loss solution—but I can’t help think of the fen-phen craze of the 1990s, which supported weight loss but turned out to damage the heart valves. Has research been done on GLP-1s’ impact on heart health?

Dr. Bahram Khadivi: Weight loss by lifestyle modification tends to be more permanent because new habits have been formed. This avoids medications and their side effects. However, there are some patients that truly struggle, and we will take any avenue for weight loss, because we know it will help them. These medications are indicated for patients who have risk factors for heart disease, and [we] also take into account body mass index. Widespread use of these medications is concerning as we don’t know [enough about potential] long-term side effects, such as loss of muscle mass and effects on vision.

Dr. Jia Shen: GLP-1s are very popular for weight loss, but they also have cardiovascular benefits. [Previously,] some diabetes medications were shown to improve [blood] sugar but also lead to worse cardiac outcomes, so a lot of the newer diabetes medicines have to prove that they’re not harmful to your heart. Because of that, [researchers] measure cardiovascular outcomes when they’re testing these medicines in the population. [A landmark trial] looking at semaglutide in diabetics found about a 26 percent risk reduction in cardiovascular endpoints. Then they took that one step further and asked, “Well, do we find [a similar] benefit in people that have obesity, but not diabetes?” It was true—there was about a 20 percent relative risk reduction in cardiovascular outcomes.

We find that not only do people lose significant amounts of weight with [semaglutide]—I believe it is around 15 percent of their total body weight—they also have vast improvements in their blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, and inflammation. Their whole cardiometabolic panel gets better. These medications, we feel, are very safe and very good for the heart, and I will prescribe them as a heart medication for people that need them.

Dr. Doug Gibson

What are some of the latest breakthroughs in the field of heart disease treatment, and what innovations will we see in the future?

Dr. Bahram Khadivi: Our ability to treat structural heart disease—we often think of blocked arteries as heart disease, but heart disease can also involve the structures of the heart, such as heart valves and muscle. Historically, diseased valves were treated with open heart surgery, [but] we now have the capability to treat multiple heart valve disorders minimally invasively. This field has really come a long way, and we can avoid open heart surgery for many patients. Structural heart procedures are done [by accessing] a blood vessel in the groin, neck, or upper arm.

Half of the procedures that I perform today were not available 10 to 15 years ago. This is also true for robotic surgery, where [what was once] a large, open surgery can now be accomplished through small incisions. Everything is headed towards the minimally invasive route.

Dr. Jia Shen: There’s always something new in cardiology. For people that have really advanced disease, we have a mechanical device that can take the place of their heart. If the heart cannot pump anymore, we can put in something called a BiVAD—a biventricular assist device, or a mechanical pump—that can actually bypass the heart completely.

With transplantation, we take out the old heart and give you a new heart. One new innovation is that we now have a special machine that pumps the heart [outside of the body]. We can take the organ and put it onto this machine, and it keeps it good and alive longer so that we can actually travel greater distances to give that heart to a potential recipient. It’s very high-tech and very sci-fi.

I think one of the things that will transform the field more is the use of artificial intelligence. UCSD is looking at different algorithms that can identify heart disease in ancillary scanning—so let’s say you get a CT for something else. We can use AI to comb through these images to see if you could have an increased risk of heart disease, so maybe we can identify that disease earlier in young patients.

Dr. Doug Gibson: In general, I would say genetic-based therapies are most exciting. Any illness that is the result of a single gene mutation is on the target list for a real cure in the near-to-intermediate-term time frame.

In my specific discipline, the most exciting advance is pulsed field ablation, a new way to treat abnormal heart rhythms, specifically atrial fibrillation. I’m a cardiac electrician, if you will—the formal job title is cardiac electrophysiologist. I specialize in abnormal heart rhythms. We treat arrhythmias by threading catheters through the veins in your leg up to your heart. We then use these catheters to destroy the abnormal heart muscle that causes the abnormal heart rhythm. We used to [utilize] heat or cryotherapy to destroy the abnormal heart muscle. We did it this way for many years, and it worked, but it could be dangerous, and it suffered from a lack of adequate success.

As of February 2024, instead of burning abnormal heart tissue to get rid of it, we use something called pulsed field ablation. [It’s] a once-in-a-career revolutionary shift in the way we treat atrial fibrillation. Instead of heating or freezing abnormal heart muscle, we’re delivering microsecond— soon to be nanosecond—pulses of energy to the cardiac tissue. [Those pulses eliminate] only the abnormal heart cells that we are targeting. This results in less collateral damage and the ability to deliver what we know to be the effective dose safely, [meaning] shorter, safer, and more effective procedures. Adoption of this new technology has been widespread and robust. At Scripps, we participated in preclinical research and the pivotal clinical trials that led to FDA approval. This allowed us to get early access to the technology for clinical use.

Sharp HealthCare President and CEO Chris Howard

Incoming Cuts to Medicaid Questions

The July 4th passage of the Trump administration’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” will have significant impacts on Medicaid in the US. Sharp HealthCare President and CEO Chris Howard explains how it may affect patients in San Diego.

What is Medicaid, and who is covered by it?

Chris Howard: One-third of San Diegans are covered by Medicaid, which is known as Medi-Cal here in California. Medicaid provides health insurance coverage for low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people with disabilities. It’s a federal-and state-funded health insurance program, so the states provide funding for a portion of it and the federal government provides a different portion for it.

What are the planned cuts, and how will they impact San Diegans?

Chris Howard: The passage of the 2025 federal reconciliation bill, known as HR1, puts

many individuals at risk of losing their healthcare coverage. New eligibility and work requirements and coverage restrictions will result in more people being without insurance. In many cases, these are people who qualify for Medicaid, but they’ll lose their coverage because they aren’t able to complete the cumbersome paperwork process.

It’s also important to note that HR1 made significant changes to the Affordable Care Act’s health insurance exchanges, like Covered California, where small business owners, part-time and gig workers, young adults, and others who don’t have health benefits through their employers can shop for and purchase private insurance plans, often at reduced cost, some of which has been subsidized through tax credits. In San Diego County, there are more than 164,000 people who have purchased their health insurance through Covered California, and 88 percent of those people received tax credit help to reduce the costs. So, as this bill takes that away, some of those individuals will decide that healthcare is too expensive, and then they won’t buy it.

HR1’s restrictions on tax credits and its new renewal and validation processes [are] going to make it more difficult for people to receive healthcare insurance coverage. For Sharp, being the largest provider of medical services in San Diego County, we are keenly aware of how significant the loss of this coverage would be for the most vulnerable patients. This includes patients from fragile newborns in our neonatal intensive care units to people receiving end-of-life care in our hospice homes.

All of our local healthcare systems are dedicated to providing exceptional health care regardless of an individual’s ability to pay. But this will place extreme pressure on hospitals, in particular, and unfortunately, that could lead to decreased services or other challenges as hospitals simply try to bear the cost of this care without compensation. The entire healthcare system in San Diego County will be extremely burdened.

Is there anything providers and institutions can do to help mitigate these effects?

Chris Howard: Advocacy is our first and foremost priority. There is much that remains unknown about how the bill is ultimately going to impact Sharp and other providers in California, in part because some of the provisions of the bill don’t take place until later years. But what we do know is, of the San Diegans that are covered by Medi-Cal, a portion of them in the future will not have health insurance coverage. And so our focus right now is on county and state budget decisions being made in response to the decreased funding from the federal government for Medicaid services, and we’re closely monitoring these developments, advocating to minimize negative impacts to our patients, the community, and Sharp.

At the end of the day, the state will have to find funding sources for the healthcare that it desires to provide. We know the current status of the state budget, and we know it’s extremely challenged. The daunting part, though, is that the net impact of HR1 will be to reduce federal funding, in this case to the state of California. And so, moving forward, the state, perhaps the county, will have to understand what, if any, additional funding sources there are for healthcare coverage, because it’s going to fall on the state, in particular, to address that. That will be a headline in the coming years: How much can California fund relative to its Medicaid program, and who will pay for that?

Dr. Jonathan Bear

Groundbreaking Cancer Treatments Questions

Radiation oncologist Dr. Jonathan Bear explains the ins and outs of brachytherapy, an innovative approach to treating prostate cancer at Palomar Health.

What is brachytherapy, and what cancers does it best treat?

Dr. Jonathan Bear: The way that we treat most cancers is with external radiation, so we have a machine that delivers radiation, or high-power x-rays, through the body to get to the tumor. While we have great technology and modern treatments and we can really deliver accurate radiation, we still have to go from the outside to the inside. You can’t give an infinite amount of radiation, because, though we would get rid of the tumor, we’d harm the patient’s [healthy tissue].

Brachytherapy is internal radiation. “Brachy” is Greek. It means “close”—so the radiation is right up next to the tumor, exactly where we need it, and that allows us to deliver less radiation to the other organs and go to higher doses. High-dose-rate brachytherapy starts with a patient under anesthesia. I put catheters through the skin and do a CT scan so we can plan the radiation in three dimensions, and then we hook each of those catheters up to a radiation machine. The beauty is, because you have [multiple] channels and a computer that’s helping you, and each channel can be dosed differently, you can really steer the dose and get a lot of accuracy. The whole procedure, from start to finish, takes about three to four hours.

What the evidence shows us from numerous trials is that it translates to better outcomes as far as what we’re trying to accomplish, which is curing the cancer and minimizing side effects.

We can treat most cancers with brachytherapy. It’s most commonly used in prostate cancer and gynecological malignancies. It’s also used in lung cancer and gastrointestinal malignancies, where brachytherapy can be applied directly inside the airway or digestive tract. [At Palomar,] we’re going to start with prostate brachytherapy, and then we’re going to move on—probably toward the end of year—to gynecological cancers.

Palomar is the only hospital in San Diego County offering high-dose-rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer. What are the limits to accessibility?

Dr. Jonathan Bear: You need to be specially trained to do this procedure—it takes a lot of time and effort compared to external radiation therapy. So really what it comes down to is the training time, the effort, and the expertise. Brachytherapy is a team-based approach. It’s not just me, [the radiation oncologist]—you have to have a urologist. I have a bunch of nurses and OR staff; we have a physicist who helps with dosing the radiation. Not too many centers have the highly skilled team that’s required in order to successfully do this procedure.

What research is Palomar currently doing to push this and other cancer treatments forward?

Dr. Jonathan Bear: We’re growing our cancer clinic. We have a research team that is contracted through Palomar. We don’t have a clinical trial [for brachytherapy] right now, but that’s definitely on the horizon—I anticipate we will have trials opening up relatively soon.

Dr. Karandeep Singh

Advancements in Healthcare-Related AI Questions

Kaiser Permanente San Diego Assistant Area Medical Director Dr. William Tseng; Dr. Karandeep Singh, chief artificial intelligence officer at UC San Diego Health; and Shane Thielman, corporate senior vice president and chief information and digital officer at Scripps Health, share the latest advancements in AI and explore what the future might hold.

What new AI tools have you implemented at your hospital group?

Dr. William Tseng: One system that we implemented within the last year is the KP Intelligent Navigator. When you share your symptoms through our app, the system uses AI to assess how urgent your situation is. If it detects something critical, it won’t let you wait for a message or an appointment; it will direct you right away to the hospital or appropriate care.

The system has a built-in clinical alert feature. For example, if a patient says, “I’m having chest pain and it’s getting worse. Can I make an appointment tomorrow?” the system recognizes that as urgent. Instead of letting it sit in the queue for a routine reply, it directs the patient to seek immediate care and escalates the message for a physician follow-up.

From October of last year through March of this year, the system processed nearly three million encounters, averaging about 19,000 each day. The system is about 96 percent accurate, meaning it is very good at correctly identifying what is an emergency, with very few false alarms.

Dr. Karandeep Singh: If we want to measure the quality of care that we deliver as a health system, we have to actually look at patient charts and see, for example, “Hey, for this patient who had a bacterial infection that resulted in sepsis, did we give them all the right things that they needed?”

Amazingly, health systems are only required to read 20 charts a month to see if they did a good job—I say “amazingly” because that’s not nearly enough charts to actually get a sense of where your opportunities are to improve. And so one of the exciting areas that we’re right now getting into which is a space that I think we are leading in—is using AI to help us do that first pass and read those charts. Basically, we don’t have to only measure our quality on 20 patients; we can measure it on hundreds of patients. We don’t have to be constrained by the fact that we don’t have enough person power to do that. We can take a first pass with AI and get over 90 percent accuracy compared to having experts reviewing the same charts.

We are now piloting AI that reads through [a patient’s complete medical history] and gives doctors a kind of executive summary, so that once you have a holistic understanding of what is going on with this person, you can strategically figure out what order you’re going to read their chart in, rather than just reading things front to back. It’s much more efficient to read a chart when you actually know what you’re looking for.

Shane Thielman: We’re working with our radiologists to use a technology that takes their dictated findings and automates the clinical impression in their documentation. The idea there is to help reduce their time in documentation but also lighten some of the cognitive burden by automating and streamlining repetitive tasks. The radiologist is still signing off on that clinical impression, but the intention is to take that dictation and pull out the clinical impression in the radiologist’s notes. That’s been a more recent development.

Shane Thielman

What does the future hold for AI in healthcare? What developments might we see in the next 10, 20, even 100 years?

Shane Thielman: I’ll start off by saying I’m not much of a futurist—with the pace of advancement of technology in general and specifically AI, it’s difficult to think beyond probably the next two to three years. The rate of change will probably not ever be as slow as it is today. We’ve taken a very deliberate and serious approach to how we evaluate any proposed AI solution, with a level of caution and a degree of risk aversion so that we’re not unnecessarily impacting patient safety, the experience of our patients, and the reputation of the organization, while also building experience with using AI.

One area that I might highlight is that, historically, it has taken many years—oftentimes between 15 and 20 years on average—to translate evidence-based research into standard clinical practice. My hope is that AI will help us [identify the] connections and relationships between intervention, treatment, and outcomes in medical data and translate those into care processes more rapidly.

We have a responsibility in healthcare to continue to evaluate technology and tools that help improve care and outcomes, increasingly with a focus on delivering care in a cost-effective manner. I think that AI can really help contribute to those aims. It has the potential to help us identify disease sooner, which can lead to improved access to care and personalized treatment in order to more effectively manage and address the disease earlier. I think it has the potential, as well, to enable proactive and preventative care and help to identify patients that are at risk to offer them access to care interventions that, ultimately, will probably help them manage their condition more effectively over time.

Dr. Karandeep Singh: One place where I feel like it could really help is, when you receive a new diagnosis or you’re a caregiver of someone, there’s often this real feeling of loneliness. When someone has an advocate—a family member with them who’s asking all the right questions—they often have better outcomes. Having an AI [system] as a patient advocate, a kind of a sidekick that can help you navigate the broader system, could be a critical thing. [It would] not just tell you what you want to hear but actually tell you, “Here’s what’s next on the agenda for this year. Here’s why.”

My wildest dreams are that you get a new diagnosis and you’ve got your own AI that’s searching up all the clinical trials, helping you figure out how to get enrolled. At that moment when you’re in grief and you have all this stress on you, you really need something or someone that can take action and keep track of everything.

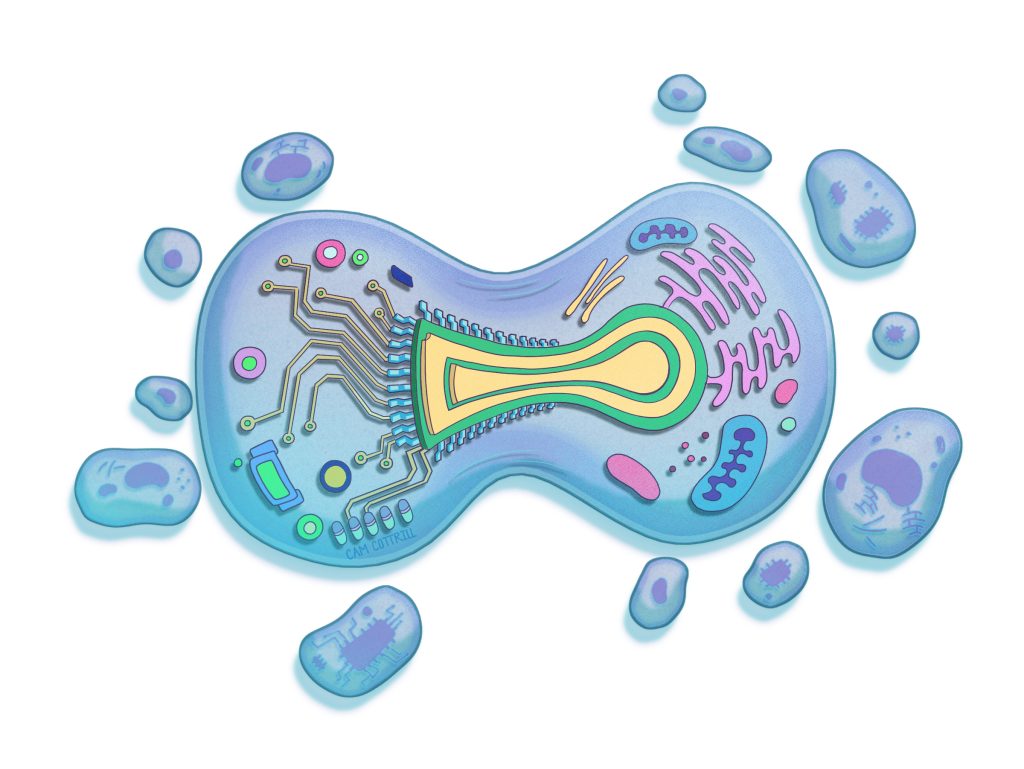

One other thing I’ll add is that, in the last five years, there have been tremendous advances with personalized treatments. Some of these things seem like science fiction, but because of advances in gene editing and advances in AI, there is a lot of potential that things we view today as incurable may be curable. Modern medicine in 100 years or 200 years may be unrecognizable because of the level of personalization we can do against things like cancer, and that’s an incredibly important use of AI that has sped things up.

Dr. William Tseng

Conversely, what are the limits of AI?

Dr. William Tseng: AI won’t replace physicians, but, in time, physicians who understand AI will replace those who don’t. AI is most powerful, really, when it makes healthcare interactions feel more and not less human.

PARTNER CONTENT

AI is an assistant. It is not a doctor. Physicians need to supply the wisdom behind its output and refine what it produces, because AI won’t always get it right.

Currently, AI is still largely language-based. It’s two-dimensional, not three-dimensional or tactile. It can ask questions, but it cannot yet fully recognize the unspoken: the silence, the tears, the nonverbal responses that carry so much meaning. Medicine is more than just words. It’s the touch of a hand in times of need. It’s delivering both good and bad news with humanity. No patient should ever hear a cancer diagnosis from a bot. That moment belongs to a physician, someone who understands, who is empathetic, who can share in the patient’s tears. These are the human connections that define healing, and they are far beyond the reach of AI.