Marisa-Crane_Book_composite.jpg

What would happen if the people we hurt literally followed us for the rest of our lives? How might our behaviors change?

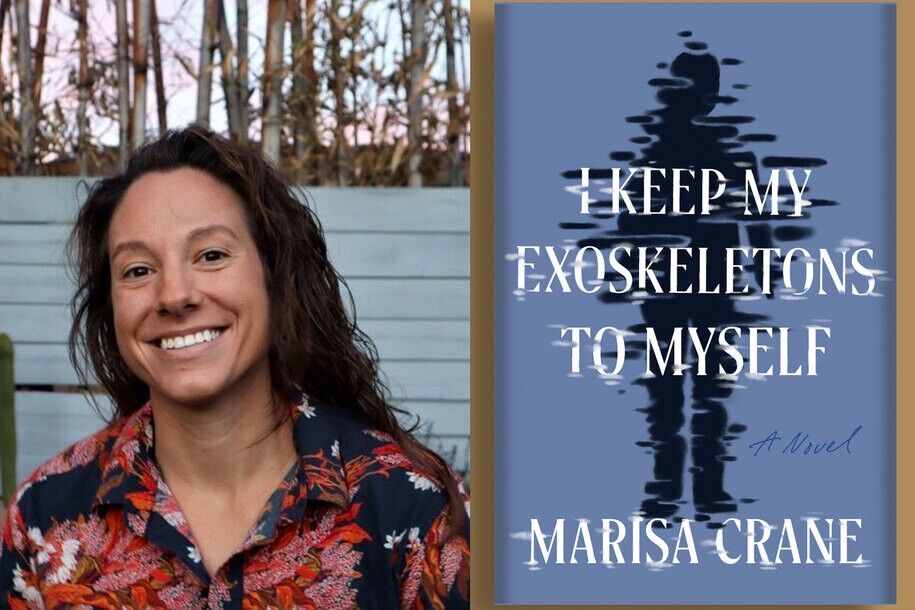

San Diego poet Marisa Crane’s debut novel, I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself, explores these questions, while tackling issues of grief, parenting, and found family. The book debuts Jan. 17.

The story exists in an alternate universe where prisons are replaced with a justice system based on surveillance, public humiliation, and shame—people who have harmed others are permanently marked by the shadows of their victims following them, resulting in an underclass of people with extra shadows known as “Shadesters.”

The speculative setting stems from a 2014 poem in which Crane wonders whether people would be so casually cruel if the shadows of the people they hurt stayed with them. Crane wrote the novel in 2019, setting the story in a beachfront setting similar to Ocean Beach. Crane now lives with their wife and son in the Rolando area.

“It was intended to shame myself into behaving better. I’d hurt some people in my life, I felt like I was irredeemable, and I thought that self-shame was the way to healing,” the non-binary author said.

However, Crane realized that shame immobilized them, preventing their healing. The novel’s protagonist, Kris, is a queer Shadester whose daughter is born with a second shadow after her wife dies in childbirth. Kris is slow to learn joy is the antidote to her shame—it takes fellow Shadesters, neighbors, and her kid to teach her to unravel her grief and self-recrimination.

San Diego poet M. Crane

“We can’t necessarily stop others from shaming us but we can insist on experiencing joy, on celebrating ourselves and our communities, and in channeling that joy in moments of profound shame and despair,” Crane explained.

In retrospect, Crane says, it’s obvious to them that Exoskeletons was written from their worst fears. “I was scared of becoming a parent and doubly scared of parenting alone,” they said.

Living under an authoritarian surveillance state brings another layer of fear. With cameras in every home, the government hovers constantly.

Crane’s experimental writing style adds to this anxious dystopian backdrop. The novel is interspersed with pop quizzes asking questions like, “Can you name an emotion other than lonely?” that Crane described as the most efficient way to interrogate Kris’s state of mind. But these quizzes also conjure heart-pounding memories of real interrogations that remind the reader no one is safe from being questioned by authorities.

And while the sharply-rendered story is suffused with anxiety, it is also interspersed with humor, warmth and love.

The novel is deeply hopeful. Crane’s characters overcome worst-case scenarios to heal and grow together. But perhaps the most important thing the characters do is simply survive. The novel serves as a celebration of queer domesticity—the day-to-day milestones of the baby growing into grade school take up more page space than political machinations.

“Solely writing about misery feels limited in scope,” Crane said. “I find that certain emotions fall short without others to push up against. If there are surprising moments of joy, of wonder and awe, of clarity and love, I find that my story feels far richer and more textured—that the suffering becomes only part of a greater landscape of human experience.”

What begins as an excavation of life in an alternate universe where Crane’s worst fears are true, ends as a reminder that no matter how dire the circumstances, we still have each other.

PARTNER CONTENT

“My pain allows me to feel my joy more deeply, more profoundly,” Crane said. “And that’s how it felt approaching this book.”