To say San Diego’s restaurant scene has gone through an evolution in the last few decades is an understatement. Gone are the days of just California burritos and surf ’n’ turf. Now we have Michelin-level chefs, award-winning design, a fine dining scene that rivals that of many big cities, and more than 7,000 restaurants in our county.

Diners are eating out more, experimenting more, and expecting more—in quality, presentation, and experience. But now everyone’s a critic, thanks to Instagram and Yelp. Add to that California’s convoluted regulations for small businesses. Just look to the closing of Cafe Chloe (RIP) for proof. No matter how good the food and ambience may be, it seems like it’s harder than ever to keep a restaurant open.

But there’s a group of trailblazers who appeared on the scene more than 20 years ago, opening restaurants before it was trendy, shaping our city’s food scene when we didn’t have one. Several are still slinging dishes today, and many of them are women.

Here, Senior Editor Archana Ram sits down with Urban Kitchen Group Principal Tracy Borkum, Barrio Star founder and The Mission Shareholder Isabel Cruz, Cafe 222 Proprietor and Bankers Hill Coproprietor Terryl Gavre, Extraordinary Desserts Owner and Executive Pastry Chef Karen Krasne, Cohn Restaurant Group Executive Chef and Partner Deborah Scott, and Saffron Thai founder Su-Mei Yu to discuss the struggles they faced to open their restaurants, what it’s like to be a woman in a male-centric industry, the new challenges they’re tackling, and how they continue to thrive.

Archana Ram: Tell me about those early days when you all first launched your restaurants.

Deborah Scott: In Little Italy I think I was the first restaurant that wasn’t Italian. Here I come, this gay woman with combat boots and shorts. I’d call my produce guy and say, “I want black plantains and chapulines.” And they’re like, “What is she talking about?” All of us here have that—we were pioneers in what we do. We had a vision, something original and creative. Now there’s so much new blood that brings so much to the table. San Diego when we started was not the San Diego of today.

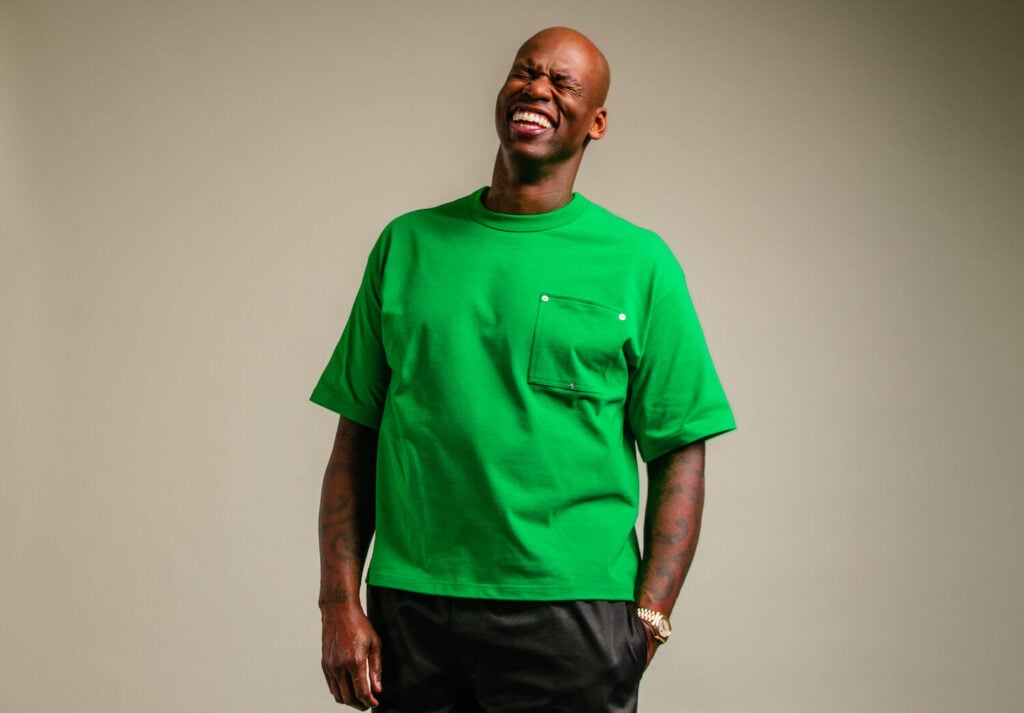

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Deborah Scott, executive chef and partner of Cohn Restaurant Group

Tracy Borkum: It was so much easier. It wasn’t easy—it never has been—but it was more fun.

Terryl Gavre: More innocent.

Borkum: The challenges we had were convincing people to try a new food item. I remember putting lentils on the menu. No one ate lentils. Or look at how popular Brussels sprouts are today! No one ate that then.

Scott: If I couldn’t sell the chapulines, I would walk around the dining room with chapulines flatbread. It was free, so they’d try it. I said, “You just have to pick the little legs out of your teeth.”

Gavre: In the beginning at Cafe 222, I’d have days when I had only a few guests. I was sitting on table one and I had turkey dinner on the menu, and I would eat it every night because I didn’t want to throw it away. This guy used to walk by and feel sorry for me in there by myself; he’d bring me magazines. I’d be in there reading magazines because no one was coming in yet. It was seven years of waiting it out.

Scott: That was very ballsy of you, to do that in that kind of area!

Gavre: But I was young and had nothing to lose. When Bud Fischer gave me my lease, I didn’t have any money for the $5,000 security deposit. We were all broke when we started; I spent every nickel I had. He explained the consequences and I said, “My dead body will be in the freezer anyway. I got nowhere to go! This is all I have.” I was willing to live in the back room for many, many years, which is now our prep room. We were young, we didn’t have families; I put everything in storage and you made it work. Nowadays you don’t have that time. Rent is too high, costs are too high.

Isabel Cruz: I gave my wedding ring for my security deposit. I let them hold on to it until they felt like I wasn’t going to run out of business and leave them without paid rent. I finally got it back after years. I got divorced anyway—I didn’t care! But that’s how we did it. On a shoestring. I lived above The Mission in Mission Beach in a one-bedroom apartment with my two kids. They stayed with my parents at first because it was too hard. I was waking up to bake muffins and scones, and little by little started adding things to the menu. I was so tired that my boyfriend would hit the ceiling with a broom to wake me up. Half the time, he’d have to physically get me out of bed.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Isabel Cruz, former chef-owner and now shareholder of The Mission, founder of Barrio Star

Su-Mei Yu: A friend of mine was helping me put together the Saffron concept. He said, “You gotta give some bread.” I said, “We don’t eat bread in Thailand.” He said, “They’ll ask for bread! What are you gonna do?” “I’m gonna cook rice.” “Rice?! People don’t eat rice in America!” I said, “I’m going to teach them.” People wanted butter and sugar for their rice! We couldn’t sell Sriracha because people didn’t understand spicy. I opened in 1985. People would come into my restaurant and ask me if I cooked cats or dogs. That’s the negative part of it. But I educated Maureen Clancy and Antonia Allegra, who were food writers. They knew nothing about Thai food!

Scott: Remember Eleanor Widmer?

Yu: She knew nothing!

Gavre: I was afraid of her.

Yu: Back then, with Italian food it was salty spaghetti with meatballs and red sauce. El Indio was making lots of money with little taquitos for a dime. Coconut? They had never heard of it. That’s what’s changed in San Diego. We’re always a little bit behind, and we catch up with whatever the scene is. The computer, iPhone, Instagram, Facebook revolutionized San Diego’s food scene. It opened an avenue for people to try it. And 90 percent of people don’t cook.

Gavre: Everybody does want to go out to eat, but it’s not just restaurants. Grocery stores and prep meals are taking over the business. There are so many other places for people to get pretty good food. We have to adapt the businesses; we have to be more delivery and pick-up friendly …

Karen Krasne: … and Instagrammable.

Scott: Oh yeah, that’s the wave of the future.

Yu: Food has become entertainment. They order something they read about, they know nothing about it, and they want to take a picture of it before they eat it.

Scott: And they want to be a critic. They want to get on Yelp.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Terryl Gavre, proprietor of Cafe 222, partner of Market Restaurant + Bar, coproprietor of Bankers Hill Bar + Restaurant

Gavre: It’s becoming less about the food. It’s about how much they spent on the build-out, and the lighting, and getting the good Instagram. I worry about that.

What got you all interested in restaurants in the first place?

Krasne I started working in restaurants in the back of house during my senior year of high school and I liked the late nights, the ebb and flow of the rushes and the team spirit. I felt the same way about it in college and during my years in France. I didn’t know it was my calling until I opened my own late-night pastry shop. I liked the idea of sleeping in mornings and having time to exercise, do things for myself, then work the evening shift.

Cruz: I always knew. Since I was a little girl, big family gatherings that centered around cooking and eating were a weekly ritual. I was always fascinated with the kitchen. Other kids were playing and I was in the kitchen trying to help.

Gavre: There was one absolute defining moment I knew. It was my birthday, and I was treated to dinner at the original Stars restaurant owned by Jeremiah Tower in San Francisco. It changed everything for me. It was the most glamorous crowd. Everyone was dressed to the ’80s hilt. Jeremiah was walking around in a beautiful white suit with a glass of Champagne, stopping by all of the tables. The food was delicious and beautiful. It was the first time I had foie gras. We drank a bottle of wine from my birth year—it was super spectacular. I thought, this man had the talent to create this feeling. What a fun thing to do. When we opened Bankers Hill, the details were important to me—what music would be playing, what the space looked and felt like, the handmade light fixtures, the vintage freak show poster.

Scott: I was an English major at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, and I worked at Steak n’ Ale in Virginia Beach. I loved literature, but the restaurant was right up my alley. Talking to guests from all walks of life and creating an environment was gratifying.

Yu: I started Saffron in 1985. Prior to that, I founded and administered a nonprofit to assist newly arrived refugees from Southeast Asia. When I realized the foundation was no longer viable, with the approval of the board members, we discontinued its operation. I was 40 years old and found myself in a career transition. I was blessed, because my companion at the time was Raoul Marquis, who owned the India Street block. The tiny, vacant space that eventually became Saffron was going to be a pizzeria, but the deal fell through. I had the brilliant idea of starting a Thai restaurant. The original concept was based on Thai grilled chicken stalls. I grew up eating it and wanted to try my hand offering the same fare at Saffron.

Borkum: Growing up, it was my dream to be in performing arts. I studied theater in London and attended BFA programs at NYU and USC. Eventually, I realized that path wasn’t for me. In between my time at university, I spent a year at home in San Diego and decided I wanted to learn how to cook. I worked my way through the ranks at a local Italian restaurant. After that, I had this innate passion for everything hospitality. It’s now a 23-year career in an industry that I obsessively love.

Since you started, the restaurant industry has really shifted—minimum wage issues, lawsuits, workers’ compensation. What has that change been like as restaurant owners?

Cruz: It’s horrific, and it’s getting worse. You don’t know when you first get in because nobody tells you about the changing laws. A big part of it is people in general, especially politicians, are making it impossible for someone to do what I did 20 years ago. I shoestringed a career, and I shoestringed employment for hundreds of people throughout my career. Now you need upward of $400,000 to open a small restaurant. You need a lawyer on retainer and an HR department. It’s really sad and unnecessary that California has set up a system where law firms are making billions of dollars closing small businesses. Small businesses close every day, and when a small farm—somebody who’s working in the dirt, trying to do organic produce—has to shut down, everybody is losing. Everyone should know about that and be afraid.

Yu: When we started doing this, you think you’re a good cook, you’re a good baker. You think, “This is going to be fun!” And you realize it’s really not fun—it’s a lot of work. The fun part is coming up with a cake or making a dish from Thailand no one ever heard of. It’s like building a castle. I started with no money. I had a partner who gave me a building until he dropped dead. I didn’t have to pay rent. A restaurant is an extension of your family, but you can’t do that today. Your family can turn against you, call a lawyer, and charge you for everything you have. I’d had my restaurant for 31 years when I sold it. I realized I didn’t want to spend all my time putting out fires.

Scott: Everyone’s in a protected class these days. You can’t look at someone wrong. Mike, my chef at Island Prime, tells a story of when he came to Indigo Grill and applied for a job. He goes, “Deb, you are so politically incorrect. You asked me where I lived, you asked me if I was married.” Once, my hostess at Kemo Sabe called in sick, so I grabbed a six-foot-two African American drag queen off the street and had her hostess for the night. But you can’t do that stuff anymore!

Cruz: You can’t ask anything. I feel like I have to call my labor lawyer every day. If you make a mistake, the punishment should fit the crime, and it doesn’t. It would be cheaper in legal fees if you murdered somebody than a labor class action lawsuit. I’m not exaggerating. Our lawsuits may not be millions of dollars, but fifty $200 lawsuits over something you didn’t even know you were violating will shut a small business down.

Gavre: My dream was to have a little place where all the employees had Thanksgiving together and we’d do holidays and close and go bowling. In the early years we did that.

Cruz: I know—I used to do that, too!

Gavre: I went out to dinner with some of my male employees for fun. Now you can’t do that. You can’t have a relationship with anybody who works for you. You can’t be anywhere and have a little wine if they’re in the room, because if something happens the next day you could be sued because it’s construed as a business function. That’s the part that’s been sad. It’s more about running a business. One day I was telling my managers, “We’re not allowed to take you to a brewery; I can’t drink with you, and you can’t drink because it’s sponsored.” I said no to about 10 things and they left really bummed. And I’m like, “You guys, wait! I used to be popular!” Everyone used to like me and now no one does. Because it comes down to me protecting what we all have.

Cruz: I used to have Christmas parties at my house where I’d cook for everybody, then we’d dance all night long. We can’t do that anymore because of HR and lawsuits and insurance.

Gavre: If two employees get amorous and kiss and fall in love for a week, then it’ll come back to you because they aren’t comfortable working in the kitchen together. And the whole back and forth about tipping is making me think about not having servers because it’s so difficult dealing with that.

Krasne: And the hierarchy of that. I would like that to completely go away. They don’t want to share.

Gavre: How are you going to get a whole group of servers, who are used to making their bundle, to share?

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Scott: First of all, they’re getting minimum wage, which they shouldn’t be. Secondly, they’re working half or less of the hours than the kitchen people are and making five times as much money.

Gavre: I’m right there with you, sister, but how do you sell that?

Scott: At some restaurants, we do a tip pool. All their tips go into a pool, then they’re divided up.

Borkum: That’s a big frustration and challenge with the politicians. We’re immediately the enemy, and we’re truly not. We’re actually employing those they want to help most. And in our business, those we want to help most are the people in the back of the house. When we sit down with the politicians and want to work with them and tell them how to help these people, they don’t want to listen. If they would consider tip credit, which we’ve brought up a million times…

Scott: … but they’re never going to do it!

Gavre: Well, the Restaurant Association spends a lot of time in Sacramento with their lobbyists. David Cohn goes, Susie Baumann goes …

Scott: … Mike Feinman goes. But it’s not lining their pockets. It’s not serving their purposes.

Borkum: We’re missing with our messaging somehow, as well. I speak to so many people that come into the restaurants. I have these conversations often, because I want to educate them. They don’t know! It’s shocking, right?

You guys have enjoyed plenty of successes, but I’m curious about the times you made a mistake. What did you learn from it?

Borkum: Failing is not a pleasant experience. For me, I had two failures. First was purchasing Laurel and not understanding at the time what it costs to transform a restaurant, not being able to negotiate a lease properly. Bad timing. Through that came Cucina.

Scott: You have to learn. Sometimes it’s a hard lesson.

Borkum: The second one was replacing Kensington Grill with a seafood restaurant [Fish Public]. It was a really, really bad decision. But again, something I don’t regret.

Gavre: But you didn’t know it was a bad decision at the time!

Scott: It brought you to where you are today.

Gavre: I opened Acme Southern Kitchen in 2012. To this day, it’s my favorite concept. I love the food, the style of the food, how homey it is. It was really hard to close it. It was three blocks outside the East Village, it was a bit too close to the [E Street] post office, and people didn’t want to cross those streets to get there. It was the beginning of the whole gluten-free, vegetarian, let’s-eat-clean thing—Southern food is none of that. I thought, “They’ll still come. I eat biscuits; they’ll eat biscuits!” It was a miscalculation. Now I look at Instagram and Southern food is the rage! It was wrong place, wrong time. I had other restaurants I needed to be at. If I were 28, it probably would still be there because I would’ve worked every shift.

Only 19.7 percent of restaurant kitchens are run by women, a staggering number considering 47 percent of America’s workforce is female. Is discrimination an obstacle?

Borkum: We get asked this question a lot. I’ve started to feel almost guilty answering, because you want to stand up for the women in our industry. I was shocked by the numbers. We’re a group of strong, independent women with a conviction that this is what we’re going to do and we’re going to make it happen.

Gavre: I never felt I had a leg down because I was a woman. I still don’t feel that way.

Scott: It’s easier to come up with excuses why you can’t do something. “Oh, it’s a male-driven industry.” Well, it’s what you make it, and you’re an individual. You’re not a woman, you’re an individual. The more excuses you come up with—suck it up, do the job, and make it happen. I’m tired of people feeling entitled with reasons why they can’t function as well as somebody else. If that’s the case, find something else to do. Life is tough—make it work.

Borkum: But why do you think it happens? If you look at those statistics, it’s shocking.

Gavre: Did any of you get asked on a survey if you felt harassed?

Scott: No way.

Yu: Occasionally you get hit on by a customer who would say, “Do you ever go out?” “So, you ever get off work?” “Can I help you with the dishes?” It’s like, “C’mon. Go away.”

Krasne: I’ve fished off my own pier!

Gavre: That’s where we spend most of our time! I have to admit—if I wouldn’t have met them at the restaurant, I wouldn’t have met them at all. I remember the days as a cocktail waitress in my 20s—we’d have to wear spandex dresses and high heels and I did it happily because I knew that’s how I made my money. If I wanted to be a server, I could’ve worn a tuxedo shirt and black pants, but it was quicker money and shorter shifts. So I did it, not thinking I was degrading myself in any way.

Scott: You did what you had to do.

Gavre: I did. I was saving money for my restaurant. I know that it existed. Some cocktail girls would go out with the manager or whomever. But I went home.

Borkum: Certainly, we all have had that experience of the screaming asshole chef that’s degrading everyone, but I don’t think that particular chef would’ve been any less degrading to a woman than men in that time. It was everyone.

Have any of you dealt with sexual harassment among your staff?

Scott: People got harassed then, but they either left or dealt with it. They wouldn’t file a lawsuit.

Borkum: I’ve terminated someone for taking advantage of a position where they made other team members feel uncomfortable. We very quickly acted on it. It’s a positive statement for where we are today. We’re more responsible to be protective of our employees. There’s the extreme side of it, too—I now have an HR person full time. I only brought them on two years ago. Before, we didn’t feel like we needed it. Now you need the attorney on speed dial.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Gavre: How do you control other people’s behavior? We’re responsible, and that’s the hard part. It’s like having all your kids keep their hands off each other.

Scott: It’s when you don’t act on it when the problem comes in.

Gavre: And creating the culture in the first place.

Krasne: You’re really trying to create a culture of appropriateness. You can’t change people. You set your policies up to fish them out faster. When you get someone inappropriate the whole vibe can change instantly.

Borkum: A positive for being a woman-owned business is that a lot of people who work for you—there’s an expectation, but I think we live up to it, that we’re more compassionate, our motherly instinct is in place to take care of people. Hopefully that filters through our business.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Gavre: It’s in our DNA to be nurturing. It might be a bit of a softer kitchen. Maybe.

Scott: Well, not back in the day for me! Maybe now.

I know that owner-patron relationship is pretty sacred for many of you.

Scott: Those relationships are such a huge part of our business. Some of my best friends are people who’ve been coming to the restaurants for 25 years. Regulars become close friends. That’s the culture, because we all live and breathe it. I spend 80 percent of my time in the dining room. I like the way you can walk through and go to their table. You can tell they’re excited you’re there. That’s the most fun experience—being out there with people.

Gavre: And if you open up something new, they’re the first people at the door. That’s an important part for me—they know they’re going to see me every once in a while and I’ll remember their kids’ names. Especially at Cafe 222, I would see people in clothes from the night before and they’re all in love now. Five years later they’re married and they have kids, then their kids are in college. Karen, don’t you love knowing people enjoy your cakes? When you see all the memories that have been created around your cakes?

Krasne: In the last 15 years I’ve become much more reclusive. I’m not a front person because I’m not able to switch hats comfortably. I’m either front or back, but don’t make me come out to the table to say hello. It’s not my comfort zone.

Yu: My customers think I’m part of their family because our food is health oriented. We got a lot of people who were sick who wanted to come in. They’d tell me, “I have this and this and this—what should I eat?” If I was there, I’d make something special for them or recommend something. I had a special relationship with my customer. When I sold my restaurant, people I saw would come hug me and say, “Where have you been? We want you to come back!” It’s like sending your kids to college. You gotta cut the ties.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Su-Mei Yu, founder of Saffron Thai

Gavre: I’ve gone into Tracy’s place in Kensington and Tracy, operator of many years, she’s hostessing! I’m like, “What are you doing hostessing?”

Borkum: When I’m really, really desperate!

Gavre: You’re always about two people calling in sick from working the door. Last time I walked into Indigo Grill, there was Ms. Scott. I loved it! I love seeing these women in their places, and if I do, I know other people do. It’s part of the fun.

You’ve built empires, and many of you have new projects debuting soon. Where do you get the drive to keep going?

Scott: It’s because we’re all type As. I’m sick because I’m always looking for new things.

Borkum: It’s the need to be creative. I think you’re right—you used the word “sick.” It’s a sickness that we have to keep going and going.

Scott: If you’re going to have an addiction, it’s not as bad as some addictions.

Borkum: Food is a super-personal thing in our world. And I don’t think we stop enough to recognize the significance of what we’re providing to our community. It sounds so spiritual and ethereal, and obviously we’re not thinking in terms of that day-to-day, but it’s an addiction to provide that experience.

Scott: It’s an intimate exchange.

Borkum: It is! And we want to provide it on all levels. Our environments are really important to all of us. The space also tells that story, and then our style of service is very personal. Then the food speaks for itself. It’s in our blood. It’s hard to let it go. You get home at night and go, “Wow, I had a full house. They were smiling and happy and we filled their souls with who we are.” There’s a real positive.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Tracy Borkum, Principal of Urban Kitchen Group, including Cucina Urbana, Cucina Enoteca and Cucina Sorella

In terms of your brand and restaurants, what are you most proud of?

Cruz: That I still have a pulse after all this time!

Scott: It’s a miracle.

Cruz: It is a miracle! Oh my god. Everything we went through to open, how hard we worked and thinking about how much harder it is now—now I got a breather from everything going on. I know exactly what my next move is going to be. I’m teaming up with Tami Ratcliff, who used to be at Cafe Chloe, and we’re going to work on a couple projects. We’re simplifying. Food is about well-being, and for me, I feel better when I eat a certain way. That’s going to be next—having those things on the menu.

Scott: For me, it’s creating the brand “Deborah Scott.” The fact that when I walk into a dining room, people are whispering and wanting me to come over, or people are coming up to me at Costco. It’s creating that culture that isn’t me, but it’s something I helped create. I’m proud of the way it’s recognizable and that it does have its mark in time. My most fun thing to do now is take these chefs up to the next level, make them shine, because I’ve had my time in the sun. I still enjoy what I do and love my guests, but I want to cultivate other people. That’s a focus for me now.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Borkum: I’m proud of being in this group trailblazing our way in San Diego. All of us individually have made a mark and created businesses that others have tried to emulate. I’m proud of Cucina, especially at the time we created it, and the statement it made that you can dine on a much-less-expensive budget and still have the same quality and experience that we weren’t used to back then. When someone leaves the restaurant, I don’t necessarily want them to immediately say, “I loved this dish or that server”; I want them to just say, “I really enjoyed being at Cucina.” There’s nothing more to ask for.

Krasne: I spend a lot of time being grateful that a little idea of mine is able to raise a child and sustain a marriage and travel and go to yoga and walk dogs—all this stuff I love. I’ve never wanted to own tons and tons of restaurants, because my life is so important to me. Every day I try to live the mantra of the name of my company and what that means to me. I’m going to use the best ingredients and I’m going to charge for it—but I’m going to deliver. I try to have that permeate throughout my staff. I have a dozen and a half people who’ve been with me for over 20 years. My front staff has been there for over 10 years.

Scott: The cool thing about what you do is that it comes through in so many restaurants. I see a Karen Krasne cake every two to three days in my restaurants. That’s cool!

Krasne: I’m in people’s weddings, birthdays, anniversaries. I get the juicy good stuff. That’s really fulfilling.

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

Karen Krasne, owner and executive pastry chef of Extraordinary Desserts

Yu: I wanted to open a restaurant that teaches people about food without being in their face. That teaches people they could eat healthy inexpensively, but eat well if they don’t feel like cooking. I’m the oldest one here! I’ve been in business a long time, but it’s time for me to do something else. I was very fortunate to sell Saffron to a family that’s like my family. They came and fixed my ceiling when it collapsed! They had more business strength than I did. It’s not the same, but my face is Saffron. The imprint of the recipes was created. It was an important part of my life. But Saffron can go on with these wonderful people.

Gavre: I’m proud I’m still here in my 26th year. I still love to get up and go in every day. I’m proud that I recognize my customers and that they’re following my career. I’m proud I’ve employed people who’ve worked for me for 15 and 20 years. I have a server—this is the American dream—when I hired him he spoke very little English. He started working for me 18 years ago. Beautiful English now. He works days for me and nights at Best Western. He put three kids through college. He bought a house in Point Loma, then he bought the house next door, which he rents. Every day when he comes into work, he’s in the most wonderful mood; he brings everyone up. I’m proud that I was able to keep the waffle house going so he could do all that. All of us have that story, of employees who’ve worked for us and gone on and bettered their lives. I’m also really proud when people say, “Hey, aren’t you the girl with the waffle on your head?”

Scott: Everyone remembers it

The Women Who Revolutionized San Diego’s Food Scene

PARTNER CONTENT

From left: Isabel Cruz, Su-Mei Yu, Deborah Scott, Terryl Gavre, Tracy Borkum and Karen Krasne