Our need for new is nothing new—it’s just becoming stronger. Blame the whirlwind of reinvention that is the tech sector. Whereas planned obsolescence once bothered American consumers, we now demand a revolutionary new version of the iPhone every year.

For a long time, restaurants seemed immune to reinvention culture. People loved having “their spots”—dependable, unchanging restaurants that served as satellites of their homes. A favorite table at a restaurant with a long history of quality was just fine.

“Now, I think restaurants need to reinvent or at least refresh themselves every eight to 10 years,” says Mike Morton, Jr., president of The Brigantine. Beloved by locals for its swordfish, beef stew, three-dollar fish taco happy hours, oysters, and ice-cold beers, “The Brig” has been quietly giving itself a gigantic facelift over the last 10 years.

In the ’60s, Mike Morton, Sr. and his brothers owned a liquor store in Point Loma (now Trader Mort’s). They used to watch the area’s famed fishermen unload prize swordfish at the dock. The Chart House, then the hottest seafood restaurant in town, made the seafood restaurant business look easy. “So in 1969 my dad and his brother had the crazy idea to take a second mortgage out on their mom’s house and open a restaurant on a shoestring budget,” says Morton, who now helps run the family business with his wife, brothers, and about 1,200 employees.

Morton brothers of the Brigantine

The next generation: Mike Morton, Jr. (left, with brother Mark on right) took over the family business and now works to carefully evolve the flagship restaurants to cater to the modern diner.

The next generation: Mike Morton, Jr. (left, with brother Mark on right) took over the family business and now works to carefully evolve the flagship restaurants to cater to the modern diner.

They took over a duplex on Shelter Island Drive [now Miguel’s Cocina], originally an insurance office and flower shop. Out of the gate, they struggled. The senior Morton and his wife, Barbara, cooked, washed dishes, waited tables, poured drinks, handled accounts. “My dad’s favorite time was the weekend,” explains his son, “because the banks were closed. At one point they didn’t have enough money to make payroll, so my dad sold my mom’s car. I’m not sure she ever forgave him, but they’re still married.”

Mike Morton, Sr

Opening day: Mike Morton, Sr. opened the first Brigantine in 1969 with his wife and brother.

Eventually things got better—mostly because the Mortons resolved to stay open to 2 a.m. When The Chart House closed down for the night, the employees and other locals would head to The Brig for nightcaps. The late-night scene saved them. In 1973, they were able to open a second Brigantine in Coronado, across the street from the Hotel Del. In ’82, they opened their first Mexican concept, Miguel’s Cocina, using family recipes from their employee Javier Alaniz (thank his relatives for their esteemed white sauce). In 1999, they rounded out their portfolio with The Steakhouse at Azul on Prospect Street in La Jolla.

Now, 45 years later, Brigantine has 14 locations and three different concepts. Their general manager at the Coronado Brig, Eileen Montgomery, has been there since it opened. Their regional VP, Pat Walsh, started as a dishwasher 38 years ago.

It’s a San Diego institution, which comes with its own set of advantages—like customer loyalty, a recognizable brand, and bulk buying power. But a 45-year-old chain of restaurants also comes with its disadvantages. Mainly, staying relevant. The cult of new-new-new has never been stronger in the restaurant world. How can a nice family place once heavily decked with nautical paraphernalia and lacquered wood compete with the hip, designer restaurants that seem to open every three months? (Have you been to Little Italy lately?)

“If you look at the way big brands have evolved, you can see a 180-degree shift,” says Tom Penn of San Diego restaurant consulting group Real Restaurant Solutions. “As brands rolled out in the last half of the 20th century, there was value in the predictability and trust people had in a brand. Customers will go to a Starbucks in a different city because they know what they want, the risk is reduced, and they feel more secure that they know what they are going to get. A good brand is competent in delivering consistency.

“But the shift is on,” says Penn. “The level of sophistication of consumers continues to grow, so they are demanding more quality and unique experiences.”

Morton acknowledges that loyalty among their regulars is key to their success. “But you don’t want to age out with your guests. We had to take a good, hard look at our places.”

A series of moves within the Brigantine business plan has kept them in the game for the long haul.

Turn it Inside Out

Brigantine Old Logos

Brigantine new logo

In 1984, Harpoon Henry’s seafood restaurant in Point Loma closed. It was basically across the street from the original Brigantine. The Mortons loved the idea of a second-floor balcony overlooking the harbor. “So we literally closed on a Friday and moved in there on a Monday,” recalls Morton.

The view was nice. But it was the live oyster bar with the miniature performance kitchen that really started a new era. “My folks and some senior people had been scouting restaurants in San Francisco and the East Coast,” Morton explains. “The live oysters were great, but it was more that people could see the kitchen action happen right in front of them.”

In the past, restaurants kept the kitchen in the back of the house so that the grimy, unsexy mechanics of producing food didn’t dwindle the magic of the final, grandiose meal. By inverting that setup, The Brig turned cooking into an attraction itself. As the success of Food Network has shown, Americans get a primal satisfaction from watching food being made. Instead of CNN or ESPN on a TV above the bar, you can watch your fish taco get dressed. As we’ve seen with the success of Chipotle and In-n-Out, having an open kitchen also increases the trust level of an increasingly wary dining culture.

“People really responded to that,” Morton says. “They could have a seat and watch their food being made. Every Brig location would have an oyster bar from that point on.”

The Uncluttering

Earlier this year, Mike Morton realized his company’s website was less than optimal. In the third quarter of 2013, over 40 percent of OpenTable users booked a reservation using a mobile device. The company website was comparably analog.

On the advice of Ballast Point owner Jack White, an old Point Loma high school friend, Morton called MiresBall, a San Diego creative agency. The original plan was to overhaul the website, but MiresBall felt the Brig’s brand needed a little more TLC.

“There were about nine different logos printed all over the place,” says MiresBall creative director, Scott Mires. “You could tell it had evolved organically over time, with each restaurant kind of adding its own spin. But it was confusing to the customer.”

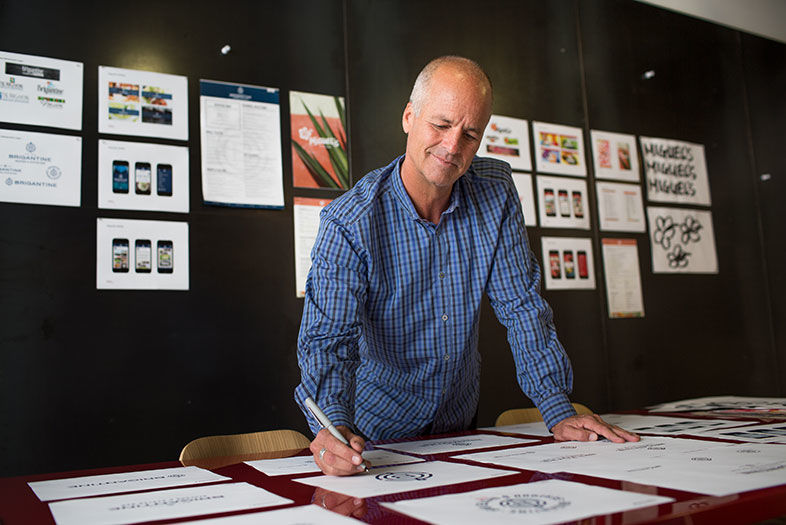

Scott Mires of MiresBall

Fresh eyes: Scott Mires of MiresBall was brought in to refresh the company’s logo, website, and overall brand image.

Fresh eyes: Scott Mires of MiresBall was brought in to refresh the company’s logo, website, and overall brand image.

The Brigantine had always given each of its locations autonomy over their personality. “We really encourage our general managers to become part of the neighborhood and let them decide what’s best,” explains Morton. The result was a scattered identity. In one place, the Brigantine was represented by a clipper ship with sails at full mast. In another, it was a swordfish majestically leaping out of the water between the letters.

“The swordfish leaping is one of the ultimate seafood clichés,” says Mires. “Hopefully we develop a good enough relationship with our clients that we can tell them some of those hard truths.”

MiresBall conducted interviews with shareholders. (“Independently,” Mires notes, “so that the loudest one in the room didn’t dominate the conversation.”) They interviewed employees. They visited all of the locations and observed, took photos, notes.

“You have this really old, built-in crowd of locals,” explains Mires. “The people that work there are old Point Loma surfers. It just has this really cool local vibe that I’m not sure was being expressed in their marketing.”

To keep it natural, MiresBall didn’t hire models when taking new photos for the website and other company visuals. There is no obligatory “pretty woman laughing over wine with her handsome friend” photo. “People can tell when they’re being marketed to,” says Elisha Lutz, MiresBall’s director of marketing.

MiresBall Creative Process

Make it modern: Creatives at MiresBall work to streamline four legacy logos into one modern symbol of the brand.

Mires adds, “The new generation is really good at sniffing out poseurs.”

The biggest overriding change in the process was to remove the clutter. At some Brigantine locations, you would have logos from every concept on a single napkin, which ends up looking like the hood of a NASCAR instead of a clean, iconic image of The Brig. The new logo is clean—a “B” in the middle of what looks to be either a periscope, series of fishhooks, or some sort of meditative circular maze. It’s a creative mashup, intentionally ambiguous. The image will be used everywhere—on menus, napkins, aprons, etc. The prosaic swordfish is dead.

The new Brig image—and website—launches this summer.

Let There be Light

Poway Brigantine then

Brigantine now

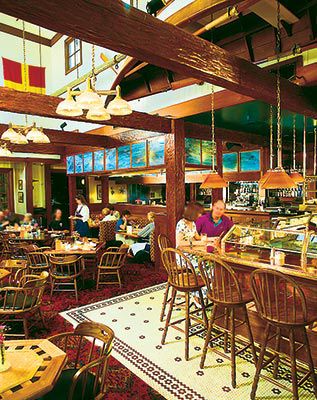

Another crucial part of keeping up with the times started for The Brig in 2004, when they face-lifted the Coronado location. The Brigantine trademark atmosphere—heavily lacquered woods, nautical tchotchkes, and dark interiors—had fallen a little behind.

The discerning ’70s diner didn’t mix dinner business with drinking pleasure. So restaurants separated church and state. “People either wanted to go have a dining experience in a dining room, or they wanted to have a drink at the bar,” explains Morton. “We had real small lounges and big dining rooms.”

Now, social dining is in. At restaurants like Monello and Ironside Oyster Co., the bar action is highly visible from the dining room, with very little barrier between the two.

“You want to make everyone feel part of that energy,” explains Hatch Design Group owner Mike Hatch, who renovated the Del Mar and Escondido locations. “We did that at the Brigantine Del Mar location. You have a central bar where you can look across at each other. And you can see your food being cooked, which makes for a good experience.”

The 1970s were also a dark time. “Old restaurants had dark bars in ’em,” says Hatch. “But today everything is lighter, healthier, indoor-outdoor. It’s almost like you’ve got a problem if you’re drinking in a dark bar.”

Almost every one of the Brigantine locations featured dark woods with mood lighting. Shadows were the overriding design theme. These days, natural light rules the restaurant scene. Roll-up garage doors. Completely al fresco restaurants. San Diego has pretty nice weather, and restaurants are framing that as a design element. At Del Mar, Hatch blew out as many walls as he could to let the outside in.

“A lot of the dark woods went away,” says Morton. “Our locations now have much more of an open-air feeling. We want to get away from dark corner booths.”

Outfitted with a full ship’s mast in the dining room, the Escondido Brigantine was the most ship-like of any of the Brigantines. “It looked like the Pirates of the Caribbean,” admits Morton. “So we spent about $2 million and blew it out.”

To renovate the entire building would’ve cost way too much, so they made slighter changes. Hatch replaced the dark woods with white tiles, and created a modern entry space so that people’s first impression walking in the door felt circa now. The new Escondido Brigantine opened in March (their Eastlake location is next on the list for renovating). Morton is very pleased with the results, although it’s not without detractors.

“We still get emails from old customers who are upset that we changed it,” he says. “But you have to make a leap of faith.”

An Evolution

That’s really it, according to Morton. That’s how a restaurant survives 45 years in the culture of new. Institutionalizing what works (swordfish, fish tacos, bulk buying power) and slowly ponying up the cost to fix what doesn’t (dark bars, scattered branding, over-indulging in the nautical tchotchke market).

“It’s an evolution, not a revolution,” says MiresBall’s Lutz. “They had this really rich history, and we weren’t going to throw that out.”

Brig Changes

PARTNER CONTENT

Light and bright: The Brigantine in Escondido