The Fishmonger star Tommy Gomes among the treasures of the sea in his Point Loma home

Robert Benson

A few months back, Tommy Gomes got an email from his producer with a series of numbers. Not a spreadsheet guy, Tommy replied, “Looks good, now will someone tell me what the **** I’m lookin’ at?”

His producer wrote back to say, congratulations, The Fishmonger was the top-rated show on Outdoor Channel. Also, congratulations, numbnuts—the head of the network was on that email you just f-bombed.

This is Tommy Gomes in a nutshell: unique and unflinchingly real.

Part of what makes him so compelling to watch on TV is that he can tell a vivid story and simultaneously give few-to-zero ****s.

He possesses a straight-answer earnestness developed from life on commercial fishing boats, where there’s no room for hem nor haw. A realism learned from doing 10 years in a federal penitentiary, where he became an artist and a man was killed next to him in line for food. Lessons learned on the streets, where he lost everything to drugs and alcohol. Lessons learned from scratching his way back, pouring every inch of his resolve into sustainable seafood, working so hard that at the end of his shift he’d often crawl into the massive coffins built for bluefin tuna and catch some sleep until the next work bell.

“I’m just lucky to be here, bro,” he says.

Chronicling a Culture At Risk

In each episode of The Fishmonger, Tommy serves as the larger-than-life docent into American fishing life. He visits with fishing families, shows what it’s like trying to navigate the modern US fishing industry. He captures the heart of a once-mighty culture that’s being pushed to the brink, if not actively being lost. He both acts as a conduit for their stories, and shares his own hard-won perspectives gained from being part of a family who’s fished out of San Diego for over 120 years.

NET WORTH“That net is about the size of Qualcomm Stadium’s parking lot,” Tommy says. “We’d take a break or a nap on there whenever we were running downwind.”

The first Gomes moved to San Diego in 1898, sustained their future with a pole and a line.

Now available in 19 countries, you can find every episode of The Fishmonger on Amazon Prime Video—except one. That episode had to be removed because in it, Tommy wasn’t shy about his feelings toward certain international fishing fleets.

Spend any amount of time around commercial fishing circles in the US, and you’ll hear the same tirade. That when environmental groups raised the issues of seafood sustainability and dolphin deaths in the ’70s, many US crews took it seriously, followed regulations, saved dolphins and turtles, and became the most sustainable fishing fleet in the world. But many commercial boats left the US, “swapped flags,” chose to do business in parts of the world where the rules were a little looser, even nonexistent. That left local fishers without jobs, and gutted entire communities built around hauling their livelihood out of the sea.

Up until the ’70s, San Diego was the tuna capital of the world, with just about every major brand—Bumble Bee, StarKist, all of ’em—based here, their massive commercial boats lined up from San Diego Harbor all the way to National City, their processing plants near the docks. The industry employed 17,000 local people at its height. Now, aside from a few boats and the small but mighty Tuna Harbor Fish Market, that culture exists largely in history books and historical exhibits at the airport.

“I’ll be the last of my family to fish for a living,” says Tommy.

To be clear, Tommy’s one of the loudest voices supporting sustainable fishing. He champions the rules; he just resents the ruin that happened when the US and a few other countries were the only ones abiding by them.

We’re standing in a bedroom of his Point Loma home that’s filled to the brim with oddities and memories collected at sea—portholes, fishing nets, dozens of poles, leather-bound photo albums, books, sextants, parts of boats that sunk, wood carvings from far-off ports. It’s part nautical Gomes Family museum, part really cool hoarding.

This room’s a special one and a hard one. It’s where he took care of his dad in his final days. Against the east window is a stained glass depicting an old man helming a boat at sea in a storm. “That’s Dad,” Tommy says. “Spent my whole first paycheck having that made for him.”

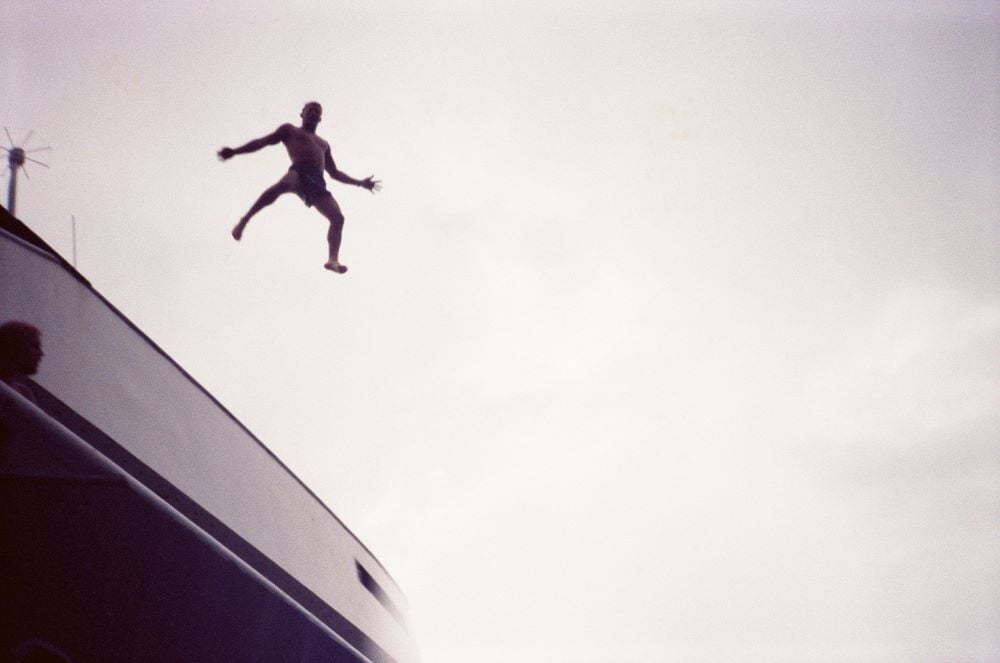

FREE TIME?“We never really get days off unless it’s really bad weather and we can’t be on deck working on the boat or machinery,” says Gomes. “This day we were drifting and it was hot out so a few of us started bailing off the pilot house—about 30 to 40 feet drop.”

Tommy’s dad took the loss of the tuna fleets the hardest.

“The old man was something special—hard worker, fished right up until he couldn’t,” Tommy says. “When the tuna boats left, he went with them. He stayed home for a while, started to deteriorate. So I got him a job driving my buddy’s sportfishing boat at night. He was happy again, all the way into his 80s. People called him Blue, like the character from the movie Old School.”

There’s a large portrait of his dad on the fireplace in the living room. In his 80s, he looks exactly like Blue. Old and scrappy and alive, a look in his eye that says, “Yeah sure I’m game.”

Tommy also looked after his mom in this home, until she passed last year. Now he lives here with his roommate, and his black Lab, Butter. Tommy’s now 60. He’s spent 40-something years earning his living off what men and women pull out of local and international waters—interrupted only by a 10-year stint where he was locked up.

On the Rocks

Tommy’s dad didn’t say much the day he drove him to prison to surrender. Just told him to not say anything that would send someone else to prison. Don’t rat. It wasn’t a statement of culpability. Just a dad telling his son how to survive.

Tommy’d gotten into drugs around age 25. Real bad.

“I remember being so bad off one time sitting at my house,” he recalls, “I put my hand on the Bible and said, ‘God, I’d rather go to prison than live like this.’ A couple weeks later, that’s exactly what happened.”

I’ll leave the details of the case to the biographers, but eventually Tommy says he found himself in the middle of a deal that went south.

“I’d never even sat in the back of a cop car before,” he says. “Up until my sentencing I thought they’d give me probation. But these were the days of mandatory minimums. I was facing 40 years to life. I went in in 1990 and got out in 2001.”

Tommy doesn’t brag about prison (he calls it “college”). Neither does he hide it.

“Prison’s a lot of things,” he says, “but it’s not cool. There is nothing cool about prison.”

I’ve known Tommy a long time. Under the right circumstances, he’ll leak out some stories. Like the time he says someone was killed with a piano wire next to him in line for dinner. It was chicken night, he remembers. There’s no glee in him explaining it. Just a human sharing a story about the unbelievable things his eyes have seen.

Tommy Gomes showcases some of the items collected from the sea over 100 years and several family generations of commercial fishing

Robert Benson

Or the time he snuck 300 lobsters in.

“We were at a camp that’s on the honor system,” he says. “It’s easy, easy time. Most guys there are near the end of their sentence. There’s no fence. So I get a buddy to drop 300 live lobsters. Everyone is getting lobsters—guards, everyone. Guys are eating six or seven, just chowing down. We throw ’em in the dumpster.

“[Later], we look down the road and we see the van comin’. Oh, no, they’re pickin’ someone up. The guards come and say, ‘Gomes.’ They drive me back to where the dumpsters were, and there are shells everywhere. I mean, all over the place. The ****ing racoons got in there and spread ’em all over the parking lot.”

Since it was an honor camp, his mom, Dottie, would stuff crab sandwiches in her sweater. Always a fishing family. Most importantly, over that long decade Tommy’s mom also made sure he saw his daughter.

“What no one talks about are the things we miss,” he says. “We don’t talk about the pain, the funerals, the births of babies, the dog, the cat. You’re missing everything, bro. My daughter was three when I went in. I missed that entire 10-year span. I would get a book, like Where the Sidewalk Ends, and she would have a copy. I’d call her from prison and we’d read together.”

BOAT FORMAL“We wore hard hats, some guys wore football helmets with full grill,” Tommy explains. “The net comes up about 35 to 60 feet above your head. Sometimes the fish get stuck in there then break loose. A 30 to 40 pound fish falling 60 feet isn’t nice. I’ve been knocked out three or four times from falling fish. As for the shorts, we’d wear nylon shorts and silk boxers. Most of the time we’d fish about 200 miles off of Mexico, Central and South America. It’s hot. You don’t want any plastic clothes or oil skins.”

In the ’90s, he says the prison system made sure female inmates had access to their kids. Fathers’ relationships with their kids were not a priority.

“So I put together a parenting program,” he says. “I taught the class. If you took the class, you got a certificate. It gave you the opportunity to sit in the TV room with your kid and watch a Disney movie. Or play a board game. It gave you an opportunity to make leather or arts or crafts with them.”

It’s the first time I see him talk about prison with pride.

“When I would get transferred to another facility,” he says, “they’d say, ‘Hey, that’s the mother****er who got us the parenting program.’”

It’s not “all good” with his daughter. Some things heal, some require more time than this life has to give.

“There are still holes in the relationship I need to work out,” he says, “but I’m very proud of who she’s become and the type of woman she is.”

Tommy grabs a giant plastic mug off a shelf in his room. “All of us get one of these in the joint—it’s where your coffee and soup and pruno go.”

On one side is a painstakingly beautiful drawing of a ship cutting through open water: the Dottie G. “Mom’s boat. Drew this with a hot needle, shoe polish, and baby oil.”

Tommy became a real artist in prison—especially in leatherworking. He’d design custom leather Bible covers for other inmates. A few ornate leather-bound books line a table in his home, each emblazoned with a different title: Thomas Gomes’ Book of Reflection, Nana’s Book, The Voyages Upon the Sea. Inside, photos of young Tommy at sea, of a Mexican helicopter escorting them out of spots they weren’t supposed to be, of boys and men and older men living their lives on decks in the middle of the ocean. They look feral, happy, ready to take on the world.

Tommy Gomes’ Point Loma home is part nautical Gomes Family museum, part really cool hoarding

He points to a leather suitcase. It’s the color of an old, oiled baseball mitt. On it, a bluefin tuna. It reads, “David E. Gomes, Master Mariner.”

“I made this for dad in college,” Tommy says. “It’s got pockets inside for his sextant, all his stuff. He took it with him everywhere he went.”

I’m no expert on prison, but it seems the offramp into unincarcerated life is neither easy nor well designed. For all the talk about prison being a “rehabilitation” system, doesn’t seem like there’s much of a plan beyond opening the gates and luck-wishing.

So when Tommy got out, it all went south in new ways.

“There’s no foundation—they’re counting on you to go back,” he says. “The fishing fleet was already gone. There was a little bit of work on the sport boats, but at that time I was an old ex-con. There wasn’t a whole lot of opportunity for me. And that’s part of the issue for myself and a lot of ex-cons, both male and female.

“I knew I was a drug addict, so I started drinking. It got worse and worse until I [was living on the streets]. I was friends with a guy named Boston James. We’d huddle up at the grease-pit dump behind Hodad’s burgers in OB because the hot grease would keep us warm. Boss Man [Mike Hardin, late owner of Hodad’s, known for taking care of locals who needed help] would come out back and give us a plain burger. He’d cut it in half because he knew we were so sick we couldn’t eat it.”

At one point, Tommy moved a few rocks around and created a cubbyhole in the OB jetty. He lined it with blue plastic tarp, had a couple buckets of vodka and a hose. Stayed there for a couple days with only those things, his lips scabbed from the stomach acid, his knees bloody from the rocks.

That was the bottom people talk about needing to hit before they finally ask for help. He started the process of getting sober. It would take a while. He went down to the only place he knew to look for work—the docks—and saw a sign: “Help Wanted: Fish Cutter.”

That ad was from Dave Rudy, owner of Catalina Offshore—a local, sustainable fish warehouse. Tommy got the job. He made friends with local chefs, raised money for nonprofits, started Collaboration Kitchen, a dinner event that taught people how to cook with local, sustainable seafood. He put on cooking demos inside the seafood warehouse. He helped develop a retail store. He made a name.

He worked at Catalina for 15 years. During the pandemic, he lost that job. His mom had just passed. Tommy had turned 60. An old ex-con adrift again. Then, another grace—a friend who’d gotten to know Tommy when they did cooking demos at trade shows suggested they film a TV show together. That friend was Scott Leysath, the cooking editor of Ducks Unlimited magazine and TV host (Dead Meat, The Sporting Chef).

“I didn’t know what the hell I was doing,” he says. “I wanted to show what real fishing life was like. Not the dramatic high-seas stuff. The real life, the families, show the wives—how they’re the anchors, the rudders. I called all my friends. Some of them said you bet, Tommy. Some of them said no way. Some fishermen go out to sea for a reason.”

Now, Gomes is about to travel to Louisiana to film his third season of The Fishmonger. In May, he’ll open Tunaville—a seafood shop at Driscoll’s Wharf in San Diego Harbor that’ll serve local seafood, caught by local people on local boats. It’s a partnership with another fisherman and local seafood icon, Mitch Conniff of Mitch’s Seafood.

When he talks about it, he just kind of chuckles. Saving himself at the buzzer yet again. The way he sees it, everything, no matter how hard or terrible, had a part in getting him here.

“Prison saved my life,” he says.

Last Ones Standing

Point Loma was built by fishing families. Offhand narratives will often claim the Portuguese created all of San Diego—just went out to sea, came back, unloaded the city onto the docks. That’s too wide a brush, of course. Plenty of cultures had a hand in the flowering of human activity here, including the Kumeyaay and pan-Asian fishing families.

But for sure, the Portuguese fishing families in the 1900s to 1950s were the ones who paved the roads and put the street lights in Point Loma. Point Loma High School needed a new gym floor? Tuna money. From the Portuguese Historical Center to the painted curbs of Tunaville to the monument to Cabrillo, this seaside alcove is very much Lisbon West.

“You could tell a fisherman lived at a house because the entire yard would be concrete,” Gomes says. “They’d paint them green. But they’re not going to waste water growing grass, especially when one of them had to be out at sea for months and wouldn’t be around to water it. If you’re gonna water it, you better get something from it. So they’d have fruit trees—lemons, mostly, for the fish. And grapes they’d use to make wine.”

You can often tell which homes belong to fishing families—modest, a boat in the driveway or side yard. In front of Tommy’s house is a small boat custom-built for his dad so he could fish into his later years. The house is a well-worn place, full of sea treasures and knickknacks. It was originally the residence of Point Loma’s fire chief.

THE SEND OFF“This one’s probably from 1978, and I was getting ready to leave on my uncle Johnny’s boat,” he says. “We’d go out for anywhere between 30 and 90 days. My dad came to see me off. That’s the old Shell dock. The canneries were down there. When the boats came back from their runs, they’d be lined up from there all the way to National City.”

When I walk in, Butter wakes up from a nap, realizes Tommy’s not right there next to him, and howls and howls and howls. Tommy’s bedroom is a converted garage, albeit one whose tall windows overlook the ocean beyond Sunset Cliffs. He wakes up to it every morning, goes to bed knowing it’s out there in the dark. The sea is what gave his family so much, the vast expanse where he grew up and learned about life and made his mistakes. The sprawling homes in the surrounding hills are full of people who’ve earned fortunes. They have the same view. But few people have earned the right to stare at big water quite like Tommy has.

“When our folks bought these houses out here in the ’50s and ’60s, they were $20,000,” he says. “Now they’re going for three or four million and the opportunity to keep fishing for a living just isn’t available. You can do a lot with three or four mil. Now these fishing families are watching as the new condos go up. It’s progress, bro; that’s just the way it is.”

Fishing families have the bad luck of earning their living in the most desirable spots. Had they pulled sustenance out of piles of dirt, the neighborhoods might stay forever.

The day I visit him, he wears a Fishmonger trucker hat. His bowling shirt is also branded. He does not miss an opportunity to brand his new life. Whereas many people are hesitant to self-promote, Tommy jumps at the chance. It’s as if, shocked this good thing is happening, he’s doing everything he can to make it stick, to imprint his mark into the world, carve it into the local rocks so he can use it as a finger hold if he’s ever in danger of falling again.

Tommy’s bedroom is full of bones, cannonballs found at sea from bygone wars, lures, international tchotchkes covered in saltwater dust. The living room is lined with couches and soft lounge chairs. His home isn’t fancy. It’s not modern and doesn’t have the signpost appliances of wealth. This is where a modest family lived out its generations, collected things that struck them one day and brought them home to keep on a shelf.

“This little device here,” he says, holding up a metal contraption shaped like a deadly arrow, “you drop out the back of the boat and every few feet it automatically ties a knot. You haul it in and can tell by the knots on the rope how fast you’re going.” That’s where knots as a measurement of speed come from.

He points to a tiny vial.

“That’s Dad,” he says, meaning his ashes. “Got tons of those things. They’re tied to buoys all over the harbor. Dad’s there, just hanging.”

Tommy Gomes, star of Outdoor Channel series The Fishmonger

Robert Benson

Through a dilapidated screen door, there’s a wooden deck that hangs on the side of the hill. Gomes has turned this into a social outdoor kitchen, with a couple smokers. Every Sunday he and Butter go fishing. Later in the afternoon he holds court here, inviting local chefs and media people and friends over to cook and talk and smoke and stare at the ocean. Tommy’s not a fancy cook. When I ask him for the secret of his very flavorful chicken, he looks at me, very serious, and laughs. “Italian dressing, straight out of the bottle, bro.”

As the last fisherman in his family, when Tommy dies, so will over 100 years of hauling a living over the side of a boat. It’s a story being played out in fishing families across the US.

So he’s going to make this final tour a grand one. Using this TV show as an homage to the people and culture of American fishing. Doing cooking demos about sustainable seafood (a video he filmed breaking down an entire opah—a round fish the size of a monster truck wheel—has been viewed over 49 million times). Opening a fish shop dedicated to local catch from local boats operated by local people he knows.

In his off time you’ll see him driving his light-aqua 1955 F-100 around town, Butter riding shotgun. He’ll occasionally lean out the window to talk to someone he knows. One of the many unofficial mayors around here.

He’ll occasionally make stops to help someone on the street. To relate, one addict to another.

“If you put shit in, you get shit out,” Tommy always says of why local, sustainable seafood matters.

It could also sum up other portions of his life.

He’s putting better things in now.