One minute, production meetings at Backyard Renaissance Theatre Company were proceeding as normal. The cast and crew for the Richard Greenberg drama The Dazzle were ready to go. Then the coronavirus hit, and California went into lockdown. If the show were to go on, it would have to be online.

The play’s licensor, Dramatist’s Play Service, gave them permission to film a performance for limited-time access. Executive director Jessica John and artistic director Francis Gerke (also two of the play’s actors, along with Tom Zohar) worked with local videographer Stand Up 8 Productions to modify their Tenth Avenue Arts Center set so each of them could maintain proper social distance.

Rehearsing over Zoom was a new challenge, since The Dazzle’s dialogue is fast paced and frequently overlaps. So they secured a warehouse space for three days where, from opposite ends of the room, they could freely talk over one another and work out the physical blocking.

Equipment setup had to be done in shifts. Project manager Anna Younce recalls, “The film crew was there for spacing, but the designers weren’t. Then the designers were there for tech, but the film crew wasn’t. The first time everybody saw it come together was on day one of filming.”

Each actor having a buffer zone worked out, since The Dazzle “literally is a play about isolation,” John says, “about people who can’t connect, who are separated within the same house.” For actions that required them to touch, a narrator character (producing director Anthony Methvin) announced stage directions from the empty seats. Despite these unique obstacles, The Dazzle received so much interest on its sole weekend run that it was granted an extension for a second. The final product was cut together with an editor’s attention to timing and point of view, while retaining its theatricality. Younce says this point was crucial to director Rosina Reynolds: “She was like, ‘I don’t want it to feel like a film. Even though we don’t have an audience, we still need to respect the form.’

She really wanted to see everything empty, that everyone’s got their own space on stage—and that this room is feeling the same thing the world is feeling right now.”

Max Macke, Jacque Wilke, Terrell Donnell Sledge, and Allison Spratt Pearce in Human Error by North Coast Rep.

Aaron Rumley

At the same time up in Solana Beach, North Coast Repertory Theatre was facing a similar dilemma with the Eric Pfeffinger comedy Human Error, when the lockdown stranded one of the five actors, Terrell Donnell Sledge, in Alabama. “I auditioned and submitted a tape,” he says, “but then didn’t get to meet anyone in person at all.”

The company decided to record the play in Zoom. Luckily, stage manager Aaron Rumley had video editing experience. “The trick was to make it visually interesting,” he says; “more fun than a standard Brady Bunch box.”

So instead of squares, director Jane Page had the idea to vignette the actors against a scenic backdrop. “I had these very vivid dreams about slating locations with postcards,” she says, “contextualizing like a matte on framed artwork.”

North Coast had two weeks each to rehearse, shoot, and edit. One difficult aspect was maintaining eye lines.

“We have to know exactly how the actors are going to be framed in post-production to figure out which way they look,” Page says. Some moments called for looking “at” one another; other times they could simply face their camera, and it was clear through context whom they were speaking to.

The dedication everyone put into the project paid off. As a viewer, you stopped noticing the newness of the format after a while because you were invested in the characters and their story—just like with any good play.

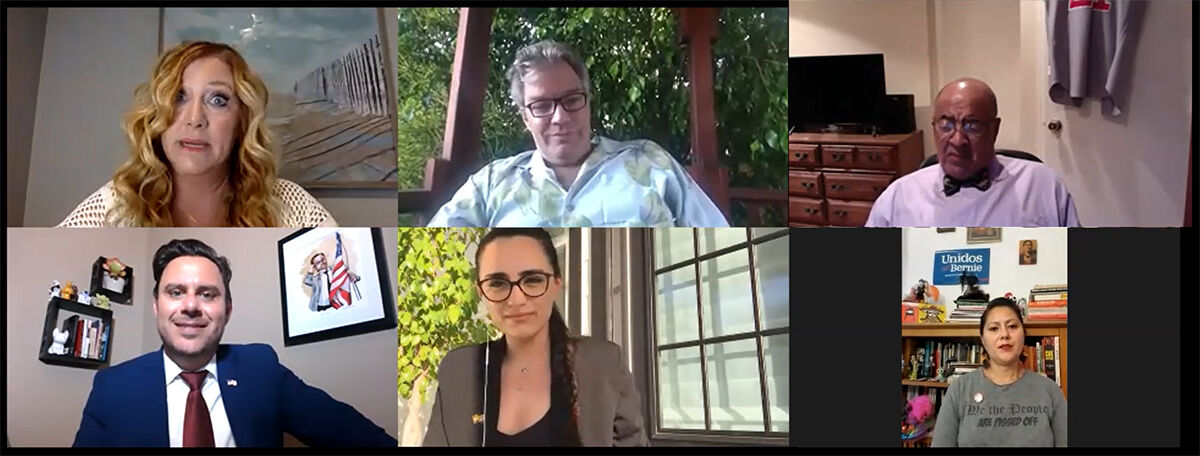

Marci Anne Wuebben, Jason Heil, Antonio TJ Johnson, Salomon Maya, Mondis Vakili, and Sandra Ruiz in Beachtown Live by San Diego Rep.

Courtesy of San Diego Repertory Theatre

San Diego Repertory Theatre put its own spin on the medium with a reprise of Herbert Siguenza’s audience-participation show as Beachtown Live. For nine weekly sessions, the fictional SoCal city’s leaders convened to discuss real-world events, first in a comedic scripted opening, then an improv section when viewers (aka “fellow Beachtonians”) could speak their mind.

Actor Sandra Ruiz says it was one of the scariest things she’s ever done. “The first time we did the breakout rooms, all I could see was someone eating. They don’t want to talk right now!” But she’s glad she stepped out of her comfort zone. “When you talk to the audience afterward, everybody’s really grateful, because they miss theater too.”

When asked if they see potential in further online theater projects, the professional opinions are mixed. Younce hopes people see the medium more as a challenge than a restriction: “There may not be as many ways to make existing theater work in this way, but then that’s an invitation to create new things.”Sledge enjoyed the experience. “It’s still performance. There are a lot of ways to do it. You can trust that if you are in the experience of telling the story, you will also discover the best ways to tell it.”

But for Ruiz, there’s ultimately no replacing the real deal: “It has been a great experience, but I honestly can’t wait to go back to doing live theater.”

What everyone seems to share is a sense of yearning for the aspects of their craft that are lost in translation. “It’s so magical to be in an audience on that day when something unbelievable happens,” Reynolds says. “Actors know if they go looking for that the next day they won’t find it. If you’re lucky enough to be there, you’ll remember it forever.”Likewise, Gerke identifies the live group setting as essential. “In an audience, we recognize implicitly that everything we’re about to see is fake. And somehow, we get to the end and all believe what’s happening. It’s one of the few endeavors where we experience whatever the hell faith is. When you’re all hooked into watching the same thing—I don’t think anyone can recapture that.” He pauses a moment, sighs, and adds, “Yeah. Let’s get a vaccine.”

PARTNER CONTENT

Tom Zohar in The Dazzle by Backyard Renaissance.

Anna Younce