When Phillip ran his family’s furniture business back in Denver, he never imagined he’d one day be a 59-year-old member of a growing workforce called the gig economy. But after the once-lucrative store shuttered during the Great Recession, Phillip—who requested his name be changed for this article—sold his house and moved his wife and daughters to an apartment in San Diego on the promise of part-time hours at a North County high school. Phillip’s wife found sales work at a big box mattress retailer, and he earned some money on the side moonlighting with a local country band and teaching private music lessons. Still, there wasn’t enough coming in to make ends meet, so Phillip started driving for Uber four nights a week.

No one is certain who first coined the term “gig economy.” Musicians have called one-off jobs “gigs” since the golden age of jazz, but in today’s gig economy, any business can hire for short-term engagements. Think temp work. Moonlighting. Alternative labor. On-call. Freelance. Contract, diversified, or on-demand labor.

The Government Accountability Office has its own label: “contingent workers,” meaning individuals who maintain work arrangements without traditional employers or regular full-time schedules. California alone has one to two million such workers, perhaps 10 percent of the state’s total workforce, most of whom are driven by poverty and a lack of full-time job openings since the recession.

Some workers in the growing gig economy—especially those who find temp jobs through apps like Uber, Thumbtack, TaskRabbit, and Amazon Flex—will benefit from new legislation introduced in February. State representative Lorena Gonzalez’s 1099 Self-Organizing Act, named partly for the tax form used by independent contractors, would amend California labor laws to grant collective bargaining privileges to gig workers who form groups of 10 or more. Federal labor law currently grants these privileges only to people who are classified as employees, which gig workers aren’t. They are not guaranteed the minimum wage. They have no employer health care, nor retirement plans, sick leave, paid time off, workers’ compensation in case of workplace injury, nor unemployment insurance if they get fired.

While gig workers like Phillip seem to be on a never-ending hustle for multiple jobs, not everybody is unhappy with the lifestyle. For some San Diegans, gig work is not only a means to an end, but a gateway to freedom. Max Bauer, 34, drives for Uber at night and hauls loads by day in order to support his wife and child and his dream of making it to the top as a pro tournament fisherman. Joshua Kmak loves his part-time gig at a YMCA after-school children’s day center, and he splits living costs with his girlfriend in order to finance his dream job as a recording artist. Gigging for a living, he claims, is his preferred way of life. Likewise for Laurie Gibson. The 53-year-old sees the freelance editing marketplace as “an open and welcoming arena.” She prefers gigging instead of full time employment because of the flexibility. “The issue is quality of life, and for me, that means being able to work when and where I want.”

The Freelancers Union describes the gig economy as a cultural shift on par with the Industrial Revolution, and points out that millennials (those born from 1981 to 1996) have in fact known no other workplace than that of juggling part-time jobs in order to earn a living.

“This is not your grandfather’s labor movement,” says Gonzalez, who represents California’s 80th District. “Our economy is changing. And we have to stay current.”

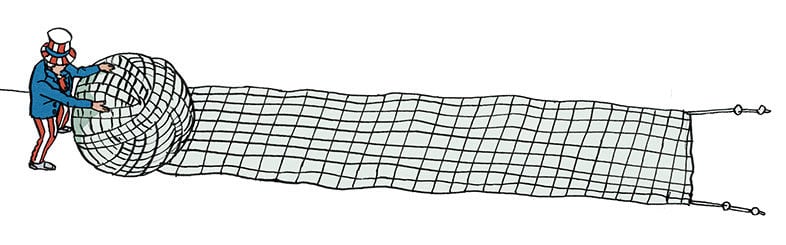

Gig workers take second and third jobs, and then they underbid each other in order to get the work.” It’s the workers themselves, she says, who are driving their own wages down. “It’s a race to the bottom, and the workers hate it.

The 1099 Self-Organizing Act would establish collective bargaining for at least some members of the gig economy. “Those workers are being left out of the discussion,” Gonzalez says, citing a recent mandatory pay reduction for Uber drivers in New York as one example. “They took a 15-percent pay cut just like that. You disagree and you’re out of work, because Uber turns off your app. Also, taxpayers have to pick up the costs for workers who don’t have protection. When businesses hire independent contractors to do work that would otherwise be performed by an employee, taxpayers end up footing the bill for food stamps, Medi-Cal, free or reduced lunch programs for students, emergency room costs, and more.”

But even assuming the act becomes law, some gig workers will still be left out: Namely the more traditional independent workers—such as artists, freelance writers, and musicians—who peddle their services to a broad variety of providers.

“They have no main employer,” says Gonzalez. “Whom would they bargain with?”

Sarah Saez, program director for the United Taxi Workers of San Diego, sees the day coming when there will no longer be any full-time professional industries. It’s simple economics, she says: “The gig economy benefits the people who own the companies.” Instead, the future will be one big gig economy, and that’s not good news.

“Gig workers take second and third jobs, and then they underbid each other in order to get the work.” It’s the workers themselves, she says, who are driving their own wages down. “It’s a race to the bottom, and the workers hate it.”

Saez sits behind a desk that fills most of her small office in the Labor Council building in City Heights. Along with a few other books on her desk is a worn copy of labor organizer Jane McAlevey’s Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell). The walls are brightened by red-white-and-blue Saez for City Council posters; she’d like to win the District 9 seat.

Making the gig economy better for the workers is part of the Saez platform. She says she knows of more than 100 local Uber drivers who want to organize, but she also has a few outside-the-box ideas about what other trades should be organized—nail salon workers, for example, who are expected to represent the company by dressing and acting a certain way with customers, but are technically independent contractors leasing their workstation from a landlord.

Meanwhile, Phillip’s health is slowly going down the drain. After he started gigging for a living, sleep became something that other people do. Phillip says that as a result, he now has high blood pressure and Type 2 diabetes. He doesn’t know how much longer he can continue grinding round-the-clock to supplement his part-time hours at the school. He gigs for the same reason that many others do—because he’s simply not able to get enough paid hours at one job. Full-time employment, he says, is the only way out. “Yes, my music career will suffer, but I have to make that choice in order to save my marriage.”

So he returns the guitar to its case, then opens up his Uber app, and waits.

Gigging for a Living

Gigging for a Living

PARTNER CONTENT

Illustration by Daniel Zalkus