Looking inside the windows of San Ysidro’s Front Arte & Cultura, a hotspot for emerging artists, bright colorful paintings and engaging sculptures by Jon Villanueva immediately catch your eye. Once you are inside, the gallery opens up into a large space where the creativity and craftsmanship of Mariel Miranda are on full display.

Her show El Viento O El Polvo, Tal Vez transforms found objects and collective experiences from her barrio in Tijuana into a grouping of sculptures that champions the power of imagination and solidarity, unseen labor, and joy. When I ask how she felt the first time she saw the show as a whole, her eyes fill with emotion.“

I think it’s my most beautiful show so far,” she says. “I wanted to be braver than ever before.” In the past, Miranda has predominantly worked within the medium of photography, collecting and collaging archival imagery. However, upon completing her Masters of Fine Art, she felt a calling to work with her hands. Her debut in sculpture triumphs—it is colorful, captivating, spilling over with emotion.

Courtesy of Mariel Miranda

The story of this show starts with the community library she and her brother opened in their front yard. One of the first activities they hosted at this library was a science fiction workshop. The siblings invited neighborhood members of all ages to engage in writing, storytelling, collage, drawing, and conversation. They pulled inspiration from their neighborhood, looking within at the challenges it is facing—and beyond, using the framework of science fiction to imagine what the future could look like through collective action and change.

The workshop culminated in a performance, documented in an arresting film on display at the exhibition, where both adults and kids donned homemade armor and marched through their barrio as a guerilla group, one that would guard the neighborhood. Despite the workshop’s science fiction focus, Miranda recounts, “[These kids] were not thinking about time travel machines, but about shields and things they could use to protect themselves.”

In their neighborhood in Tijuana, clean water is not a given and gunshots from narco violence are a regular and life-altering occurrence. At dusk, burning cars release huge plumes of dark black smoke into the sky. Their reality is one in which Miranda and her brother must debate opening the library following a day heavy with the sounds of explosions, concerned about incentivizing people to leave their homes amidst projected violence.

Miranda speaks openly and candidly about these issues, lamenting that, “We’re dealing with a new generation of young boys and girls who are normalizing the fact of living without water in their houses.” Several pieces in her show reference the tongue, paying homage to thirst, to the voice, and to stories.

She also spoke of the dangerous labor conditions in the maquiladora (or factory) in her neighborhood. Miranda, who has a deep background in sociology, points to these as examples of neocolonialism—where American companies come in to cut production costs on the manufacturing of their science-fiction future, often at the risk of those working in the factories.

One piece in Miranda’s show gives tribute to the lost limb of one of these workers and explores conversations around how to sabotage the machines and systems that are devouring her community. Other pieces use assemblage sculpture and the process of weaving, a single repetitive action that grows into an accumulation, to give visibility to this kind of labor.

Accumulation and labor have long been a tool for female sculptors, perhaps in response to the invisible labor women are often called to perform. The desire, then, to be seen, acknowledged, reckoned with, transforms action craft into pieces that consume rooms. Miranda also uses many found and recycled materials from her neighborhood.

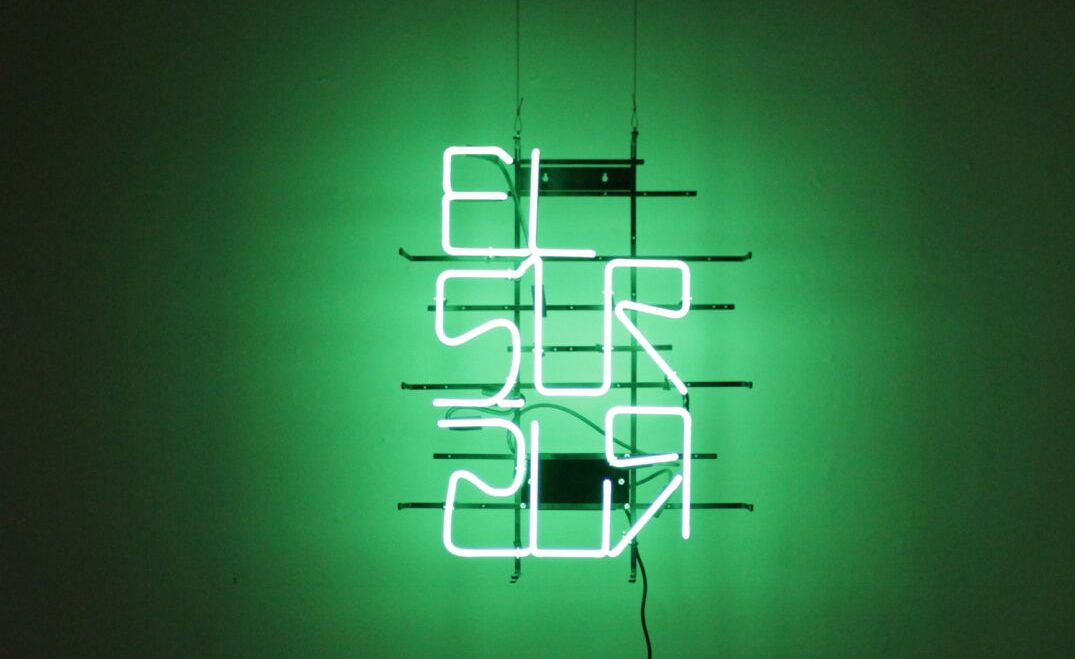

One of the standout pieces in her show “Esta criatura oscura y brillante baila y respira” (or “The dark glowing creature dances and breathes”) is a towering, suspended flow of magnetic tapes from old VCRs. Small air currents in the room and slight movements breathe life into it, and it glows eerily with the echoes of a green neon sign sculpture in the corner.

Woven threads and found items come together in a newfound brilliance through reclamation and imagination. Miranda weaves belts with the same authority she weaves threads of hope in her community. She pulls from her background of collage and treats objects as archival pieces of her barrio’s story.

PARTNER CONTENT

Her show, along with Jon Villanueva’s work, fill Front Arte & Cultura to the brink with color, youth stories, beauty, play, and transformation. The darkness is there, but belief in a better future shines above it. “Work that gains clarity through love, friendship and solidarity,” Miranda emphasizes. “That’s the future.”

El Viento O El Polvo, Tal Vez is open now until August 31 at Front Arte & Cultura. 147 W San Ysidro Boulevard, San Diego, 92173.