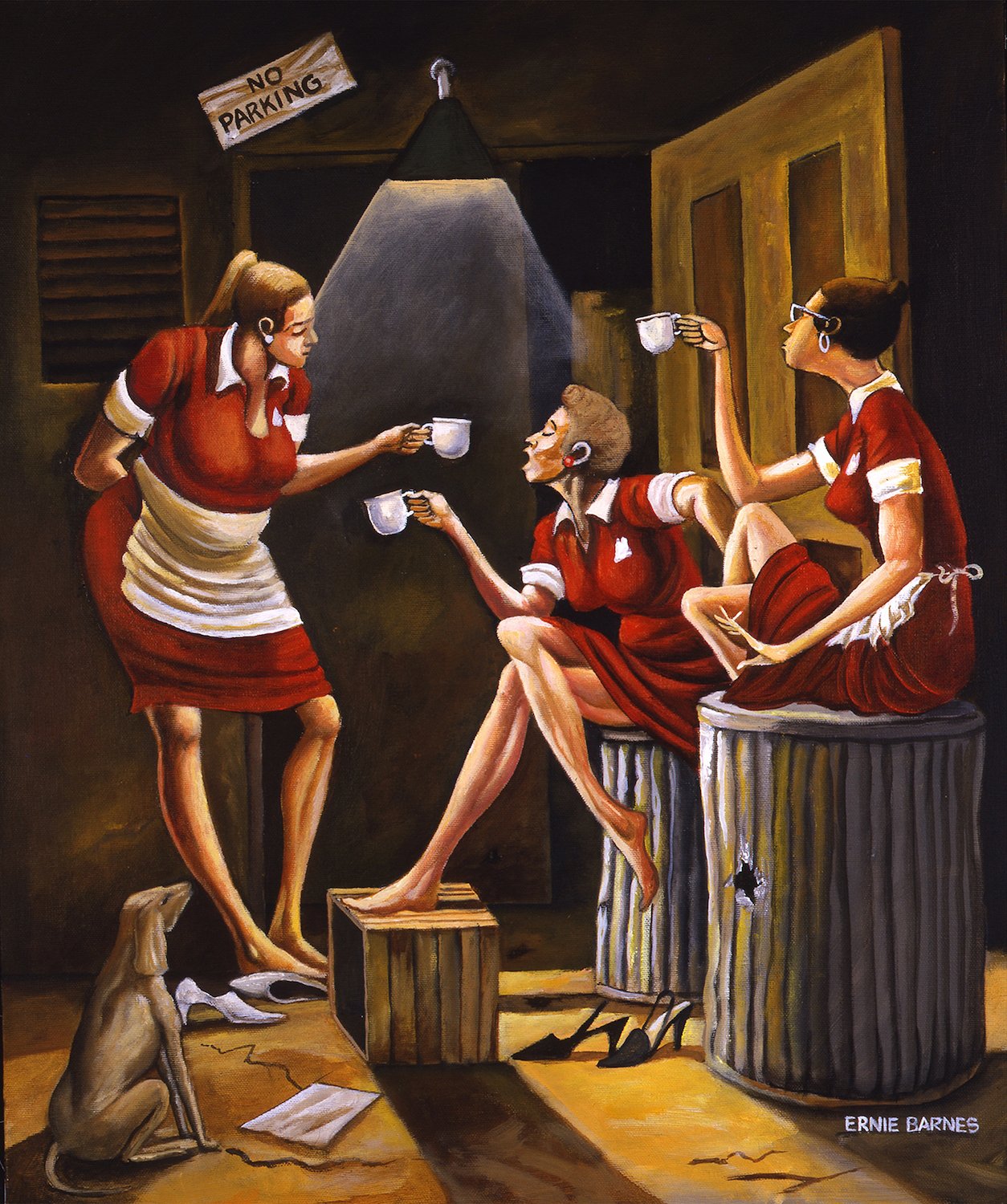

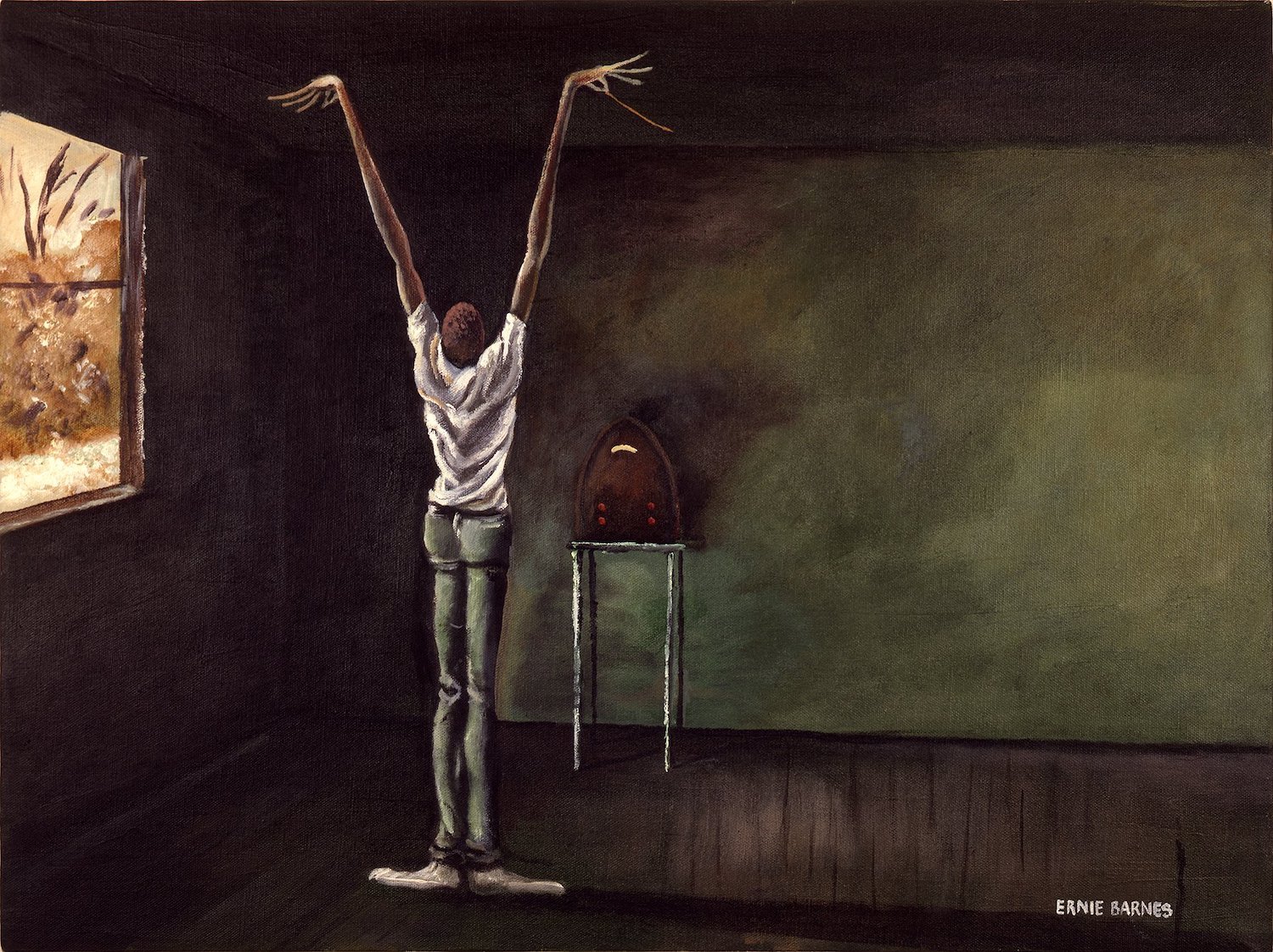

Artist and athlete Ernie Barnes painted what he saw, and what he saw was America through a rare lens. Drawing from a childhood in the Jim Crow South and time on our nation’s biggest playing fields, Barnes displayed his own particular cultural vantage on his canvases. Once you encounter his paintings—with their telltale elongated bodies, exaggerated movements, and forms alive with a musicality and quiet depth—his work becomes instantly recognizable.

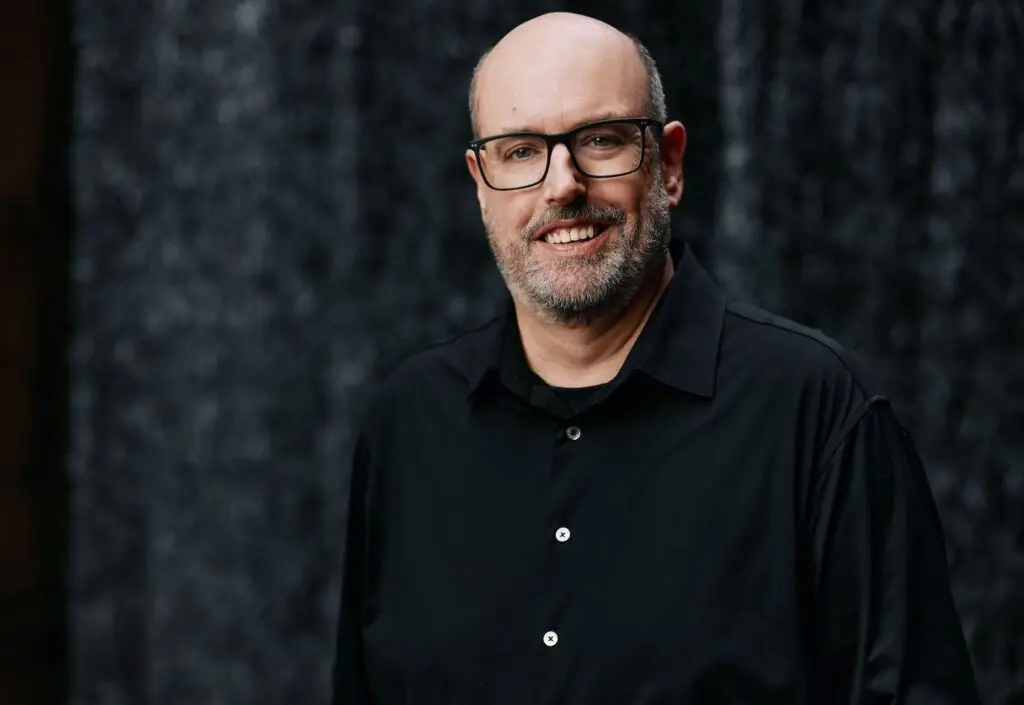

“The curve of his figures, that visual rhythm—it’s distinct,” says Derrais Carter, a Barnes fan and associate professor of Africana Studies at UMass Boston. “There’s something uniquely American about his work.” Today, Barnes’ legacy echoes through galleries and auction houses around the world, his work fetching millions. But before achieving artistic acclaim, Barnes was a football player trying to make ends meet in San Diego. Our city—and this magazine—played a pivotal role in helping shape him into a man widely regarded as the first American professional athlete to become a professional artist.

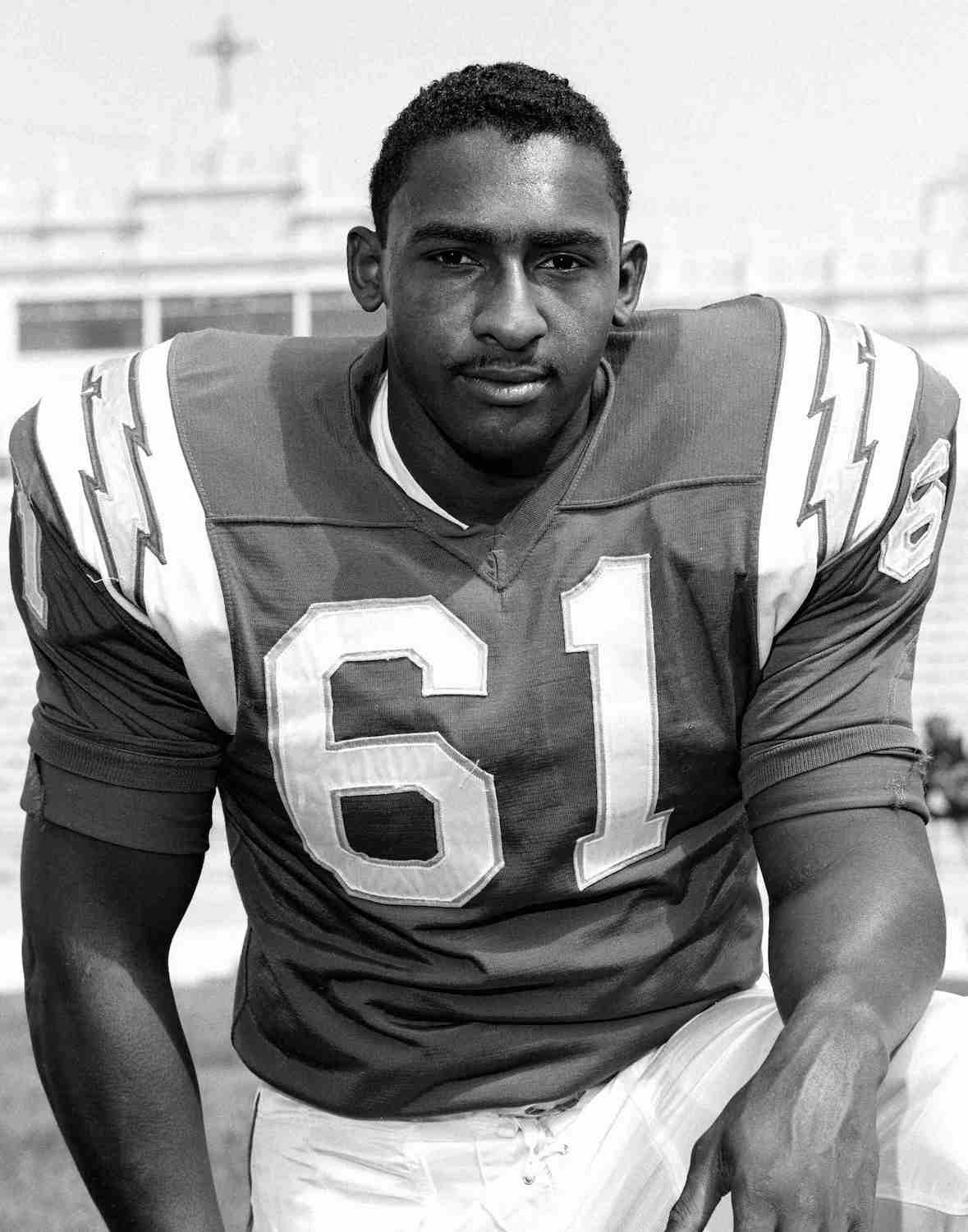

Born in Durham, North Carolina in the summer of 1938, Ernest Barnes Jr. grew up on a dirt road in a segregated nation. Gentle-natured and self-described as chubby, Barnes was bullied as a child. But his artistic inclinations were present early, simmering on a back burner while his life—and his body—grew in the direction of pro sports. With more than two dozen scholarship offers following high school, Barnes decided to stay close to home, accepting a full ride to the all-Black North Carolina College at Durham (now North Carolina Central University), where he studied art. The 6-foot-3-inch, 250-pound Barnes was then drafted by the Baltimore Colts in 1959. Barnes later said it was in the trenches of the offensive line that he learned much about human movement.

In his autobiography, Barnes said his time playing for the San Diego Chargers proved to be “a mark of [his] development.”

After a brief stint with the New York Titans, his connection to San Diego began taking shape when he accepted an offer from the Chargers in 1960, one year before the team moved from LA to Balboa Stadium.

“Even when he lived in LA, he loved going down to San Diego,” says Luz Rodriguez, Barnes’ longtime assistant and founder of the Ernie Barnes Legacy Project. “He really enjoyed the weather and the vibe, and whenever he talked about football, he preferred being a member of the Charger team.”

“For me, being a Charger satisfied my dreams about being a professional football player,” Barnes writes in his 1995 autobiography, From Pads to Palette. “It staked a deep claim in my emotional territory. It was a mark of my development.”

In the 1960s, Barnes provided a number of illustrations for San Diego Magazine, including Pulling the Guard, which ran in October 1967.

For Barnes, who found a lifelong friend in Chargers quarterback and later US congressman and vice presidential nominee Jack Kemp, San Diego wasn’t just a place to play football—it was a city of creative and personal exploration.

“When my father landed in San Diego, he said, ‘I’m home,’” Barnes’ daughter Deidre “DD” Barnes says. “He was very comfortable there. He loved the city.”

The family rented an apartment on Dream Street in southeast San Diego. Barnes set up a painting studio in a back bedroom where he could practice his craft when he wasn’t playing football.

Courtesy of the Ernie Barnes Estate

“When we were young, paintings were all around us,” DD Barnes says. “Looking back as an adult, I realize how much art was a part of his life. In our apartment, my father had easels and paint all over the place.”

While suiting up for the Chargers, Barnes began moonlighting as a freelance illustrator for San Diego Magazine. This small step in his continued development as an artist came with a small paycheck compared to what was in his future.

“When he worked for San Diego Magazine, he was trying to raise money—football players weren’t paid much back then,” Rodriguez explains.

“My father made about $600 a month playing for the Chargers,” DD Barnes adds. “He was selling art whenever he could, and, in the off-season, he worked at the YMCA.”

This illustration from the August 1964 issue of San Diego Magazine accompanied a story Barnes himself wrote about violence in professional football.

Shortly after his move to SD, Barnes met with Edwin Self, this magazine’s founder and then-editor. In his autobiography, Barnes describes Self challenging him to write and illustrate an article detailing his feelings towards the violence in pro football:

I was thrilled and eagerly began the assignment, working all day at a typewriter in the time-worn “hunt and peck” method. At the end of the first week, I presented my manuscript to Mr. Self. After reading it through, he said, “Right! I think you’re onto something, Ernie. Write it over.” I went at it again, only to be told, “It’s better, Ernie. Now do it again.” I really wanted so badly to give up, but something prevented me from hanging it up. After a series of meetings and the subsequent rewrites, Mr. Self finally said, “Ernie, we have a good article. Now illustrate it.” When “Pro Football Is Not Dirty . . . On Purpose” appeared in San Diego Magazine, I was proud. Really proud.

The article ran across four pages in August 1964. Barnes also illustrated a number of other SDM stories in the ’60s, including one by legendary SD muckraker Harold Keen.

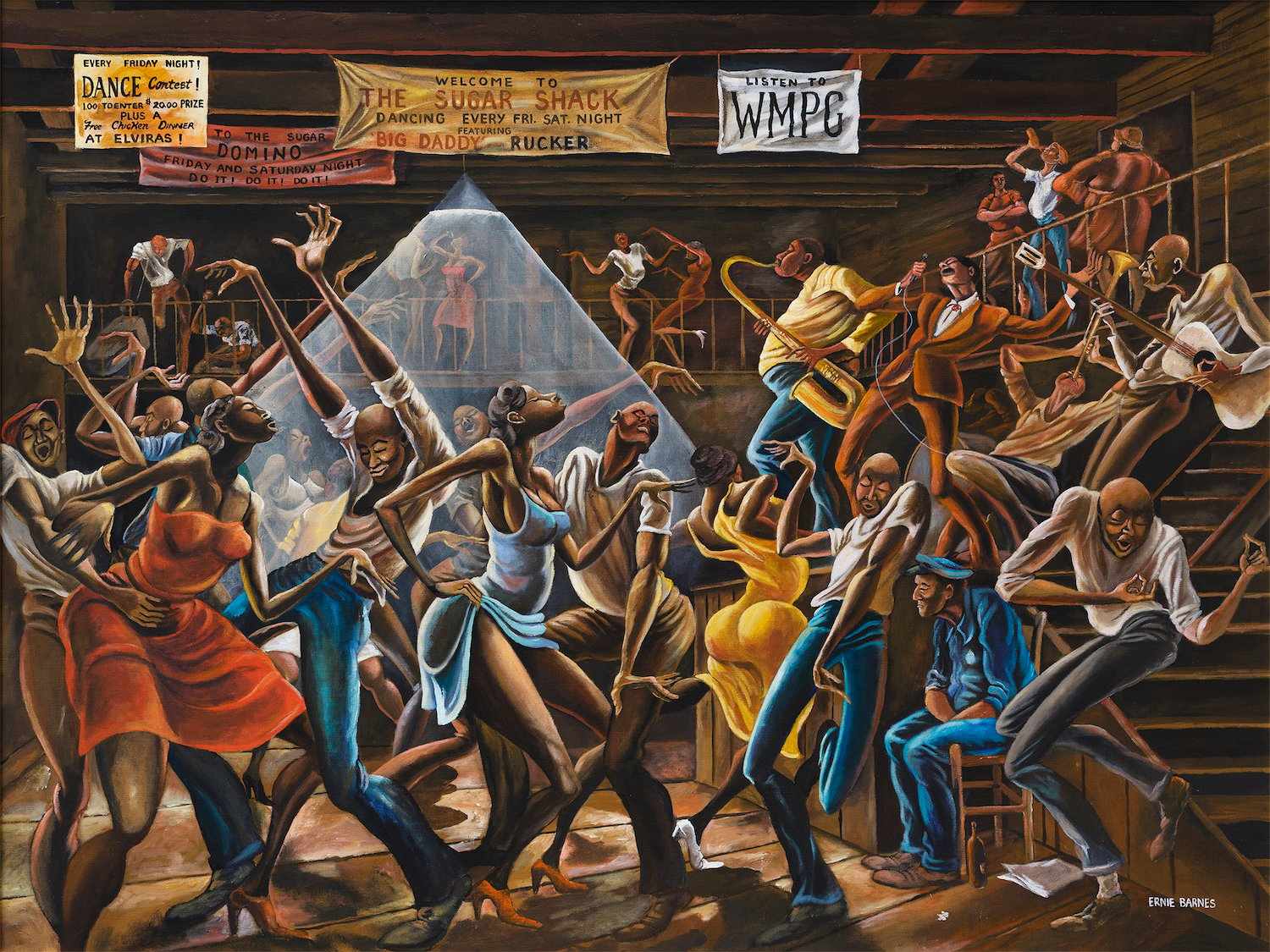

Today, when people talk about Ernie Barnes, they often start with The Sugar Shack—a 1970s depiction of a Black juke joint bursting with boogie and bliss that launched him into the crossroads of American culture. The painting was seen weekly in the credits of the popular ’70s CBS sitcom Good Times and was featured on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album I Want You. Today, the original is owned by actor Eddie Murphy, who purchased it for $50,000 from the estate of Marvin Gaye after the singer’s death. It could, however, be worth 500 times that amount—a reproduction of The Sugar Shack done by Barnes sold at Christie’s in 2022 for more than $15 million.

Carter, who grew up seeing Barnes’ work on calendars and prints in countless living rooms, dorms, and dens, says The Sugar Shack holds a special place in his understanding of Barnes.

The piece captures what Carter calls “the joy of engagement,” a quality he says runs through all of Barnes’ art. “It feels so fun to have a relationship with a painting that is serious in its unseriousness,” Carter adds. “This is a painting you can kick it with, for real.”

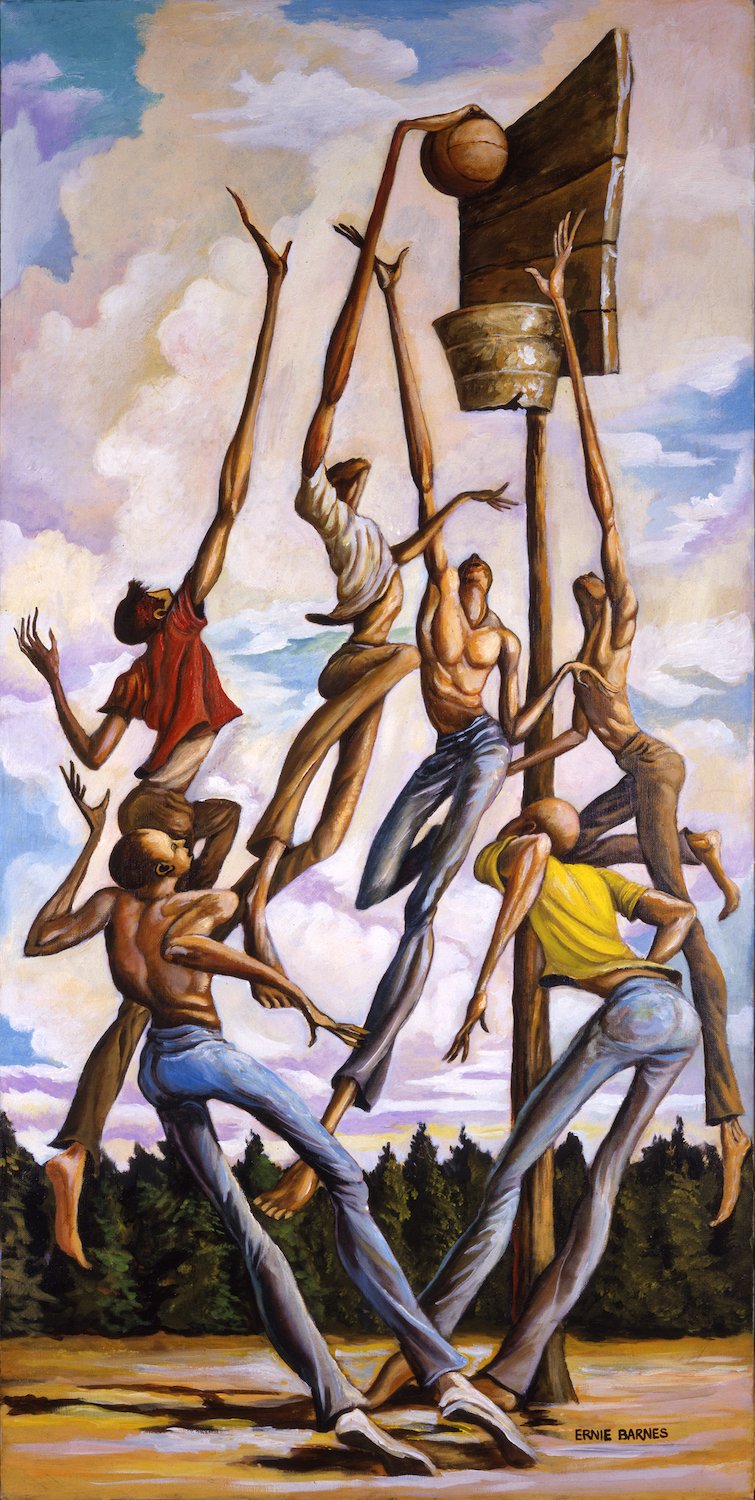

Barnes painted sports of all kinds. He was named the official artist of the American Football League and later the official sports artist of the 1984 LA Olympics.

But Barnes’ legacy isn’t just about The Sugar Shack. Following his retirement from the football field, he was named the official artist of the American Football League and later the official sports artist of the 1984 LA Olympics. His work was featured on additional legendary album covers from Curtis Mayfield, B.B. King, the Crusaders, and Donald Byrd. He was a true working artist, a rare feat for any painter, much less a Black painter whose career began before the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

Barnes called his style neo-mannerism, a nod to Renaissance Italian painters, but his work is also frequently associated with the Ashcan school, which focused on scenes of everyday life, often in poorer urban areas of the US in the early 1900s.

“His mentor [chairman of the art department at North Carolina College Ed Wilson] told him to slow down and pay attention to what’s right in front of him,” Carter explains. “To see a story even in something as simple as a shoe on the sidewalk.”

His approach gained him growing fame, even after his death in 2009.

“So many people know the work, even if they don’t know the artist,” Carter says. “The style is unforgettable, and it keeps finding ways to live on.”

Rodriguez echoes this sentiment, pointing to the enduring demand for Barnes’ paintings—as well as that record auction sale that introduced Barnes to a new audience.

“The art world finally became aware of him,” Rodriguez says. “He had a base of loyal collectors and followers, and now it’s all coming together. There are always new collectors coming in—athletes, celebrities, and people who grew up with Ernie Barnes’ art.”

Former NBA player and current LA Clippers coach Tyronn Lue recently purchased a Barnes original.

“The piece I purchased immediately resonated with me because it was a picture of a woman which conjured up thoughts of my mother and aunts and grandmother,” Lue told SDM. “I plan on adding more Ernie Barnes to my collection. Several of his basketball pieces, especially those in rural settings, remind me of my background and where I came from.”

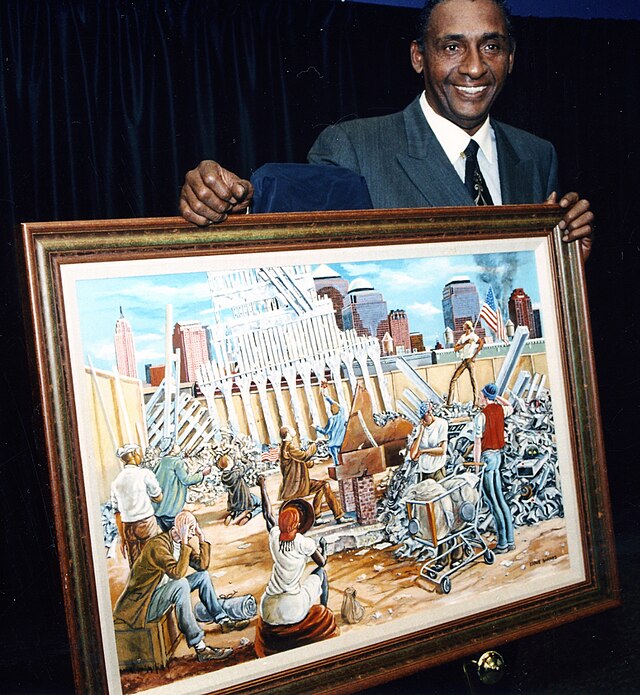

Ernie Barnes with his painting In Remembrance, 2001

Barnes’ work can be found on permanent view at museums around the country. Here in California, a sample of his work is currently on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through February 18th.

PARTNER CONTENT

But even as Barnes’ fame grows, San Diego remains an integral part of his story—a chapter that helped shape the man and the artist.

“San Diego was one of those places he always held in high regard because of the connections and the experiences he had there,” Rodriguez says.