Until the 1990s, most Americans knew tequila as harsh devil juice you slammed as quickly as possible before spending the next few hours in a sombrero, ruining lives. If you paid more than $10 a bottle, you were probably not a math major. Early tequila imported to the U.S. was subpar bordering on vile, mostly a mixta (51 percent agave, 49 percent “other sugars”). Then in 1989, Patrón marketed the idea of premium tequila with 100 percent blue Weber agave priced at almost $50 a bottle.

People scoffed. The upscaling of tequila took years, but it worked. The market flooded with premium tequilas, and Americans’ perception of the spirit changed drastically. It went from shot glass to brandy snifter, from cheap chug to refined sip. Patrón sold to Diageo earlier this year for $5.1 billion.

Sake knows this story very well. The Japanese rice “wine” (not technically a wine, but the analogy works in a pinch) has a rich history in Japan going back hundreds of years. But in the U.S. it was relegated to “sake bombs” because stateside sushi restaurants imported the cheap stuff that, quite frankly, didn’t deserve anything better. It tasted like hot socks. So Americans dropped shot glasses of it into pints of Kirin beer, and sent them down the hatch.

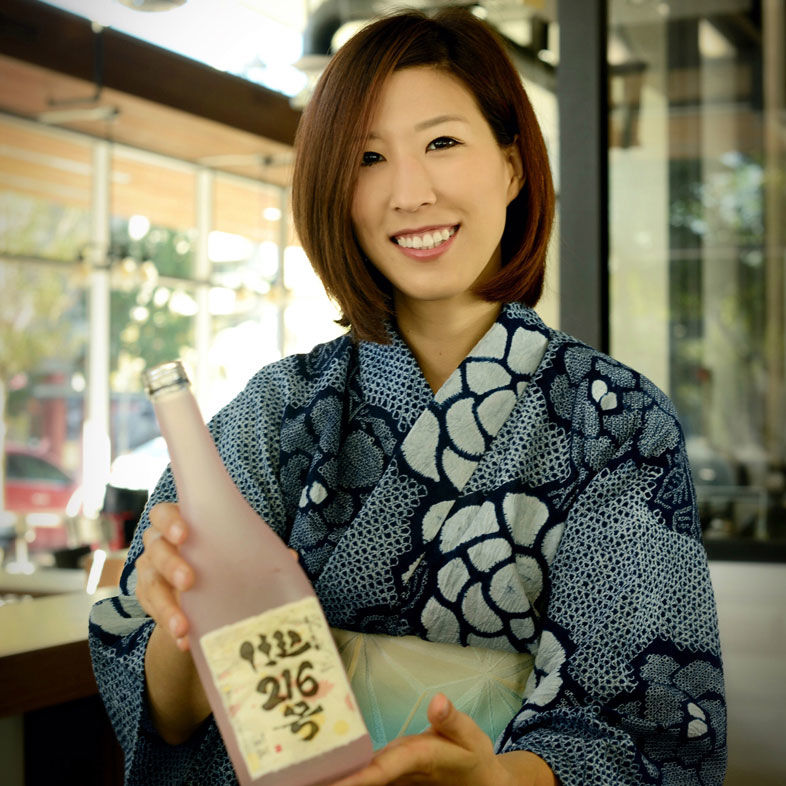

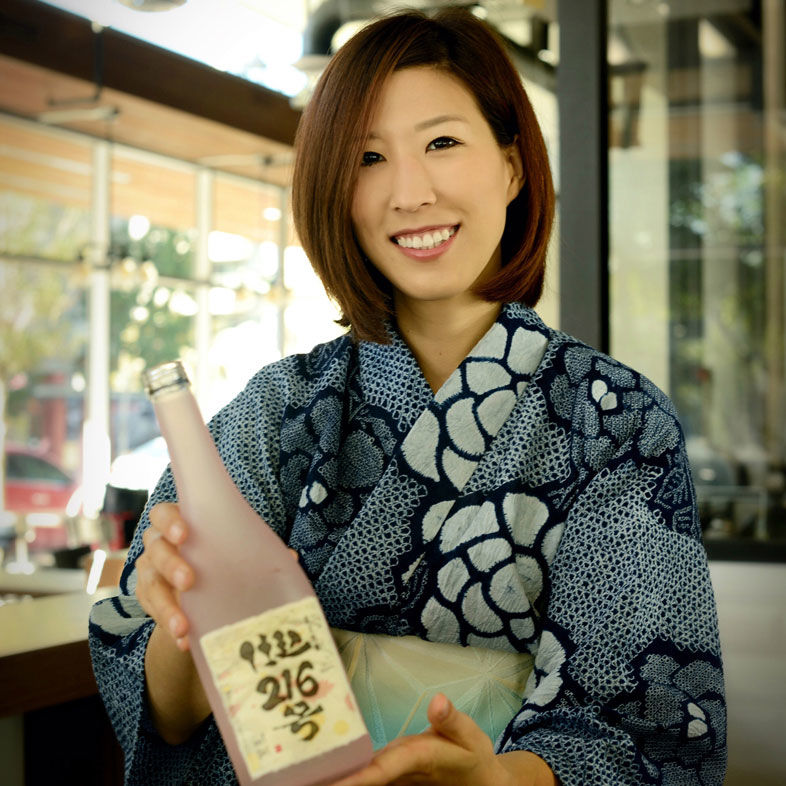

“In Japan we had no idea what sake bombs were,” says Ayaka Ito, certified master kikizakeshi (sake sommelier, essentially) and co-owner of Beshock Ramen & Sake Bar in East Village. “Friends traveling to Japan for the first time would tell me, ‘I want to do a real sake bomb in Japan!’ And I’d say, ‘Wait, what?’”

Now, sake is undergoing the image makeover that helped tequila boom. “Premium” sake now makes up 89 percent of the drink’s imports to the United States. Most of the high-end sakes are served cold, like white wine. There weren’t even classifications for sake until 1990; now there are seven: junmai daiginjo, daiginjo, junmai jingo, ginjo, tokubetsu junmai-shu, junmai-shu, tokubetsu honjozo, and honjoz. And Beshock (the name is a play off the Japanese word “bishoku,” which means “beauty of food”) has emerged as San Diego’s outpost for trying the best, under the guidance of Ito, who was born and raised in Japan.

“My grandmother loved sake,” says Ito. “Every holiday she’d be drinking and cooking. She drank the cheapest sake from grocery shopping or supermarkets. But after the war, she appreciated everything she could get. ‘I just love sake,’ she’d say. And she was right about it.”

After attending college in Hawai‘i (where sake got its start in the U.S., due to the high number of Japanese immigrants), Ito returned home to Japan in the wake of the devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2011. Ito was a long-term volunteer helping rebuild the ravaged Miyagi Prefecture. One goal of that rebuilding was to reactivate the local economy—and one of the most crucial industries was sake.

“It takes so much dedication,” she says. “To brew a sake, they kind of all live together through the season and are away from their family. For close to six months they work day and night and take turns. It’s almost like raising a baby. There’s no stopping time. They need to mix the batch and make sure the temperature is right. It represents Japanese culture working with people. They say a good group of people brew good sake, and a good sake brings you a good group of people.”

Considering her time in the United States and fluency in both Japanese and English, Ito thought she had the abilities to translate this culture overseas. When she and her partner, Masaki Yamauchi, opened Beshock in 2016, people were skeptical. The first customers would come in for the ramen, but cringe at the thought of sake.

“Some people say no because they remember that sake bomb from 30 years ago,” she says. “So I say, ‘You’re from California, right? Imagine if I said I tried a box of wine 30 years ago and don’t think California wine is worth it.’ Box sake is what most places served for a long time, but there’s a whole other part of the sake world. I bring them a glass, and they usually say, ‘Oh my gosh, what is this?’ It opens up their world.”

Serving flights of sake samplers, she was able to win over one guest at a time. San Diego’s strong craft beer culture had primed the locals for conversion.

“San Diego is a mecca for craft beer. All the microbreweries have different characteristics and stories. So people here appreciate these microbrews and the people who put effort into making a product. Sake has the same thing. The people in California already have a different palate from drinking wine and beer and tequila and mezcal. They’re really highly educated in the palate. So it was a lot easier to explain a flavor profile.”

It’s worked. The success of Beshock’s downtown location inspired Ito to open a location in Japan, with a second San Diego County location planned for Carlsbad.

“My grandma was so proud,” she says.

For an example of what guests will taste when they order the sake flight, Ito provides tasting notes for her “Sake 101 Flight” below.

Beshock Sake 101 Flight

Nine-Headed Dragon (mellow and balanced)

“The name comes from the river—this brewery uses purified well and underground water, which makes a big difference in the brewing process. It’s the most popular sake to drink warm.”

Cherry Bouquet (aroma)

“A hint of sweetness like pear and melon, and focused on floral aroma. It has a clean, crisp finish like a sauvignon blanc.”

Akitabare (traditional)

“This is a traditional, full-bodied style. The complex flavor comes from the slow fermentation process over the winter.”

A Sake Master In Craft Beer Land

PARTNER CONTENT

Ayaka Ito of Beshock Ramen & Sake Bar | Photo: Maria Pablo