at home tests, covid

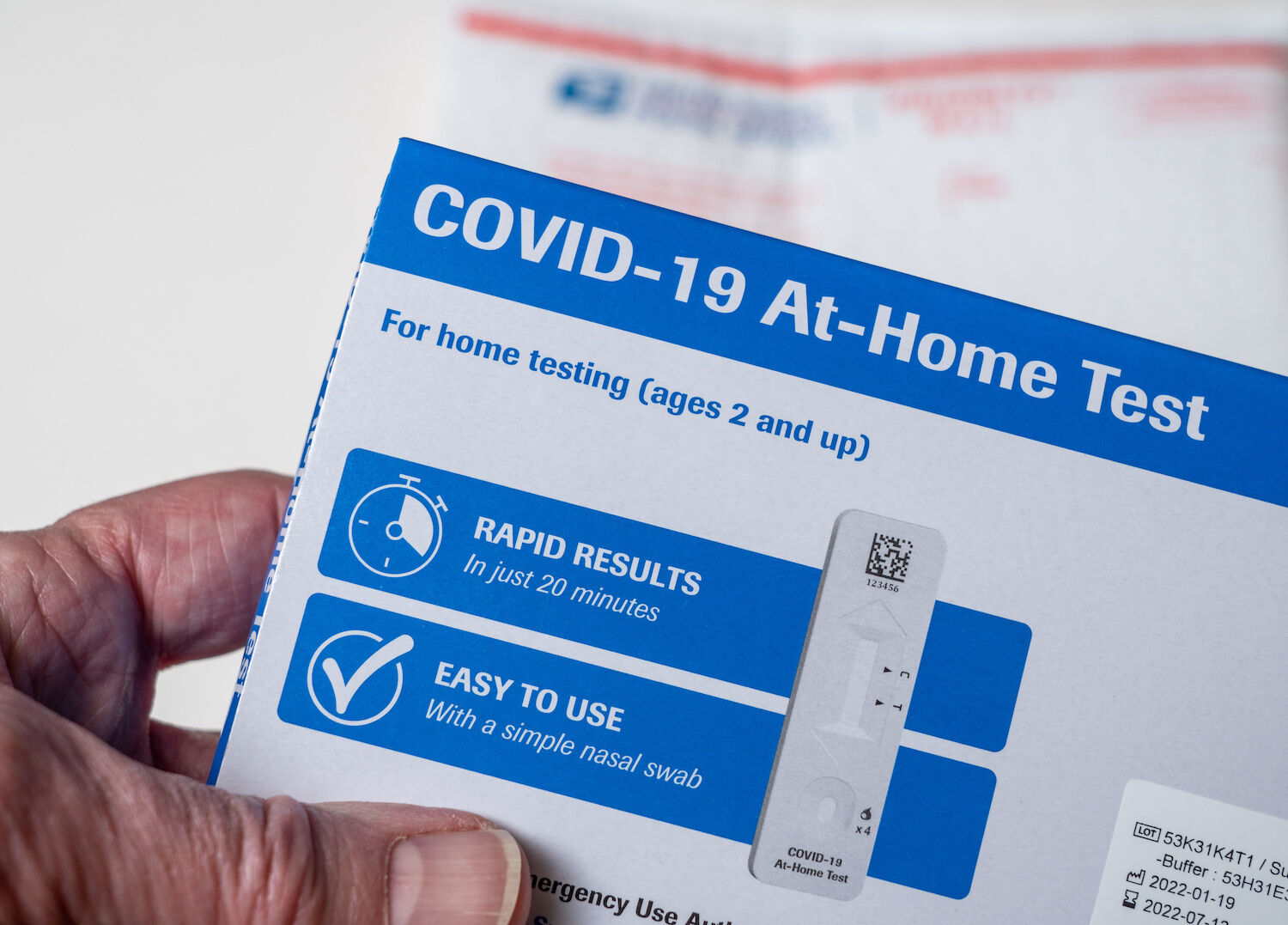

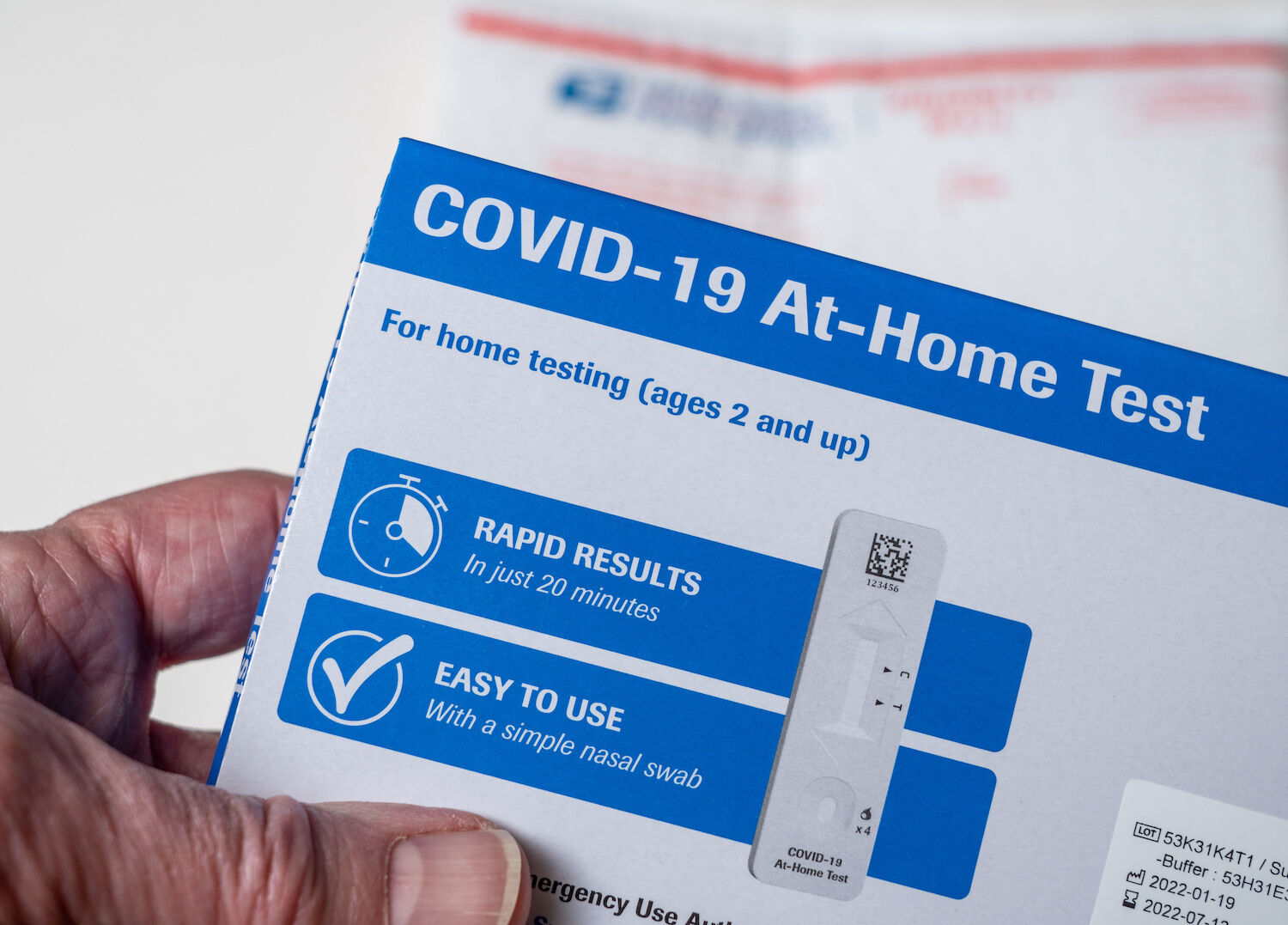

Sweating palms. Eyes fixated on tiny faint lines appearing or never appearing on little plastic contraptions on your bathroom counter. What’s it going to be? Positive or negative? To quarantine or not? How will my life change? We’ve all been there.

Testing for Covid-19 might not be fun, but the technology that allows us to test at home means we have an easier time knowing just how sick we might be. And we can thank a local scientist for the technology. Those little at-home tests for Covid are based on a medical discovery made by Dr. Eva Engvall, an 82-year-old Swedish scientist who worked most of her career at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in La Jolla.

Dr. Engvall helped invent the ELISA test—which stands for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay—with her colleagues in 1971. Her invention revolutionized medical testing. The ELIZA method works by utilizing antibodies that look for a virus or hormone in liquid—like snot, pee, or blood—revealing the result as positive or negative. “It was a real game-changer. It was a way to reduce the spread, giving peace of mind, and knowing frankly when to quarantine. Though there was a risk of false-negatives, it’s an immense tool,” said Jennifer Dailard, spokesperson at Kaiser Permanente.

Though the handy, easy-to-use tests aren’t 100 percent accurate (which medical test is?), they’re valuable initial screening tests that give patients some clue about what to do next. Call a doctor, do more tests, live life as normal. Dr. Engvall’s work isn’t just seen in Covid tests, however. When people were making jokes on social media that taking a Covid test was like waiting on a pregnancy test, they weren’t that far off. The science is actually the same.

Dr. Engvall’s invention works for dozens of medical diagnostic tests. The ELISA method is the basis for tests for pregnancy, malaria, HIV, hepatitis, muscular dystrophy, cancer, and many others. “I made this test simple. It’s a test that can be applied to almost anything in principle” said Dr. Engvall.

Previous similar tests used radioimmunoassays that took hours if not days and were actually a wee dangerous on the radioactive scale. A common initial screening test for prostate cancer is a blood test that measures prostate specific antigen. The test is based the ELISA method.

“Dr. Engvall saved my life and many others,” said Malin Burnham, billionaire business leader and philanthropist whose namesake is part of Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute where Dr. Engvall is Professor Emeritus. “When I took the blood test, it turned out I had prostate cancer. I decided to have it surgically removed. And I’m still alive. Without her ELISA test, there wouldn’t be a prostate cancer test. It’s a testament to her work.”

covid at-home test

But Dr. Engvall’s ELISA test isn’t only used for medical purposes. It’s used in veterinary science, agriculture, and even art restoration at the Getty Conservation Institute. It’s been used to figure out that plant gum was on wall paintings in King Tut’s tomb from 1330 B.C. And remember when the Taliban blew up Buddhist statues in Afghanistan? Her ELISA test was used to analyze the animal glue to help restore the 6th-century Buddhist wall paintings.

“The application of ELISA to the cultural heritage field has sparked new research. With this relatively simple and inexpensive procedure, it is possible to detect and differentiate four common binding media types: glue, casein, egg, and plant gums,” said Joy Mazurek, associate scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute who wrote her master’s thesis on the ELISA procedure at California State University, Northridge.

While Dr. Engvall’s invention has touched almost every aspect of medicine, and made a far-reaching impact in the art world and other fields, she still remains perhaps one of the most under-appreciated living female scientists. She also didn’t make a dime from ELISA. “My professor thought we should patent this. We talked to the pharmaceutical company who paid my salary. The company said, ‘oh, it’s not patentable’ … and that was the end of it,” Dr. Engvall said. She’s okay with how things went down. “Patents really prevent scientific progress. People work to avoid paying patent fees instead of using [the research] that’s out there,” she explains.

Her invention contributed to the work of the 2022 Albert Lasker Prize recipient, Dr. Erkki Ruoslahti. (Some say the prestigious award for medical research is the precursor to the Nobel Prize.) Dr. Engvall worked in his lab, and she applied her ELISA method to the project that led to the medical discovery. They’ve been partners in life and science ever since.

Recently, they bought a place with a couple of acres in Escondido after living in Sweden for two years. Their house in Escondido has sweeping views toward the east, looking out toward the San Diego Safari Park. She lives there with Dr. Ruoslahti and her five Whippet dogs that she used to breed.

PARTNER CONTENT

Dr. Engvall still goes to Sanford Burnham Prebys to work. And she says she wants to relaunch a “How to Succeed in Science” lecture series on the Torrey Pines Mesa. It was something she helped run back in the early 1980s when she first got to La Jolla. For her, passing on her experience and knowledge to other young scientists is another way to continue her legacy, even if not everyone realizes those little lines on the at-home tests are based on her work.