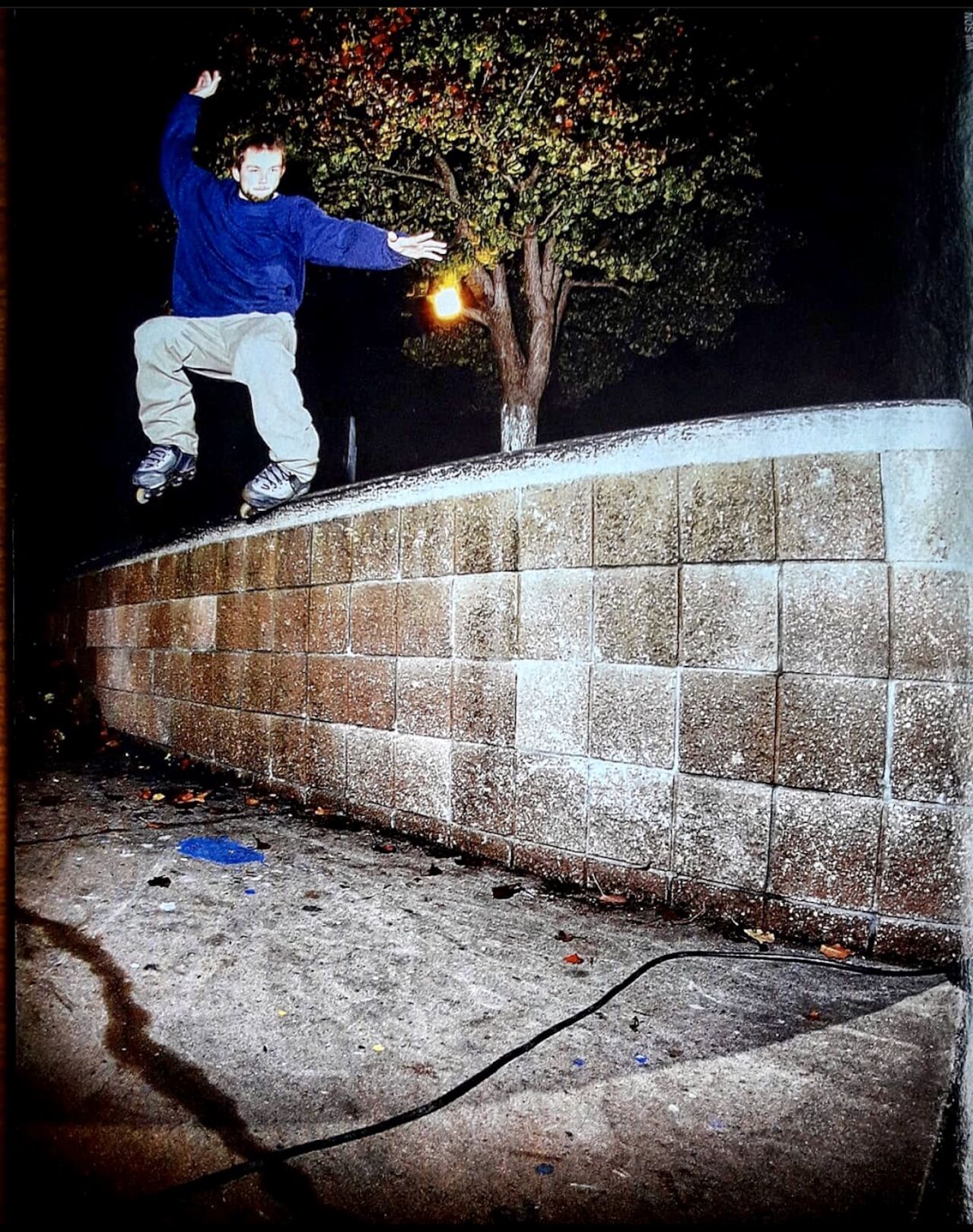

Now-philosopher, professor, and author Nick Riggle was once a professional inline skater who competed at the X-Games and played with fire.

Courtesy of Nick Riggle

What the hell are we doing here, and what does it mean to lead a fulfilling life?

Perhaps it’s due to living through Covid-19 and its aftermath that I’m significantly horrified at humanity’s social, political, environmental, and economic challenges. Whatever the reason, I find myself asking the big existential questions more than ever.

These are not questions I’m alone in wondering—the existence of university philosophy departments confirms this. Just pop into any late-night, booze-and-weed-soaked bonfire and eavesdrop on the chatter.

But these are questions that, at least in the United States, have been largely cast aside during the 20th century in formal philosophy—until recently, University of San Diego aesthetics professor and author Nick Riggle tells me. We’re discussing his book, This Beauty: A Philosophy of Being Alive (published December 2022), which provides a working manual for thinking through “The Question.”

To wit: How are we, as sentient beings, supposed to value a life we did not choose to live? We’re here, sure as we can pinch our skins, but why should we “want it, love it, care for it, make it mine?” Riggle asks.

Befitting an academic, Riggle tackles this quandary as a lecturer might, by speaking directly to readers in his text, walking them through each chapter conversationally and lyrically. The chapters appear as individually themed essays on life in general, time, the body, family, the concept of a single day, and, of course, beauty. This sprawling format is intentional.

Nick Riggle

“I don’t think, philosophically, that ‘The Question’ has a direct answer,” he says. “We don’t have enough information to have one. We don’t know enough… [W]ho we are, what we’re doing here, what the universe is. It’s all one great mystery.”

To help untangle this mystery, Riggle offers real-life examples of how to think about these concepts through relatable anecdotes about parenthood and his middle-class upbringing. He also interrogates the futility and vagueness of common inspirational phrases like “live like there’s no tomorrow,” “seize the day,” and “you only live once.”

He argues they all imply that life is precious and therefore inspire either recklessness or over-careful preservation. Both of these are overkill for the nuances of everyday life and recognizing the beauty and, consequently, the value therein.

Beauty as a subject, and the search for it, is what anchors Riggle’s entire philosophy (and book). To him, it’s very much in the eye of the beholder, something subjective and highly individual, with meaning beyond just pleasure and visual satisfaction. There’s also an inherently communal aspect. The personal and public aspects engage in a feedback loop that creates aesthetic value.

Riggle, who lives in El Cerrito, is a good candidate to explore the value of life: He’s lived many already. He dropped out of high school to pursue a professional inline skating career that took him to the X-Games and other international competitions and found him hanging out with Eminem, Dave Matthews Band, and Randy Savage by age 20.

Dissatisfied with living life rooted more in the corporeal, surrounded by material pleasures in a body-punishing discipline, he moved on to other pursuits. He got his bachelor’s degree at Berkeley after starting at community college, earned his PhD in philosophy at New York University, became a professor, married, and, more recently, became a father. There was also a stint as the head of a hip-hop-slash-folk music group in-between.

Nick Riggle

Courtesy of Nick Riggle

So why ask The Question now?

The book touches on other disciplines, but it’s fair to say that it is broadly an existentialist work. Academically speaking, this worldview fell out of favor after the writings of Søren Kirkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, John Paul Sartre, and others preoccupied with teasing out the meaning of human existence initially became popular.

For many, existentialism is too nebulous and tedious to consider. In San Diego, where championing good vibes sometimes trumps everything else, it’s easy to see how it rarely elevates beyond that aforementioned bonfire conversation. For Riggle, fatherhood provided a good opportunity to dig in.

Zooming out more widely, after decades of the decline of organized religion and the rise of buffet-style spiritualism linked to astrology, crystals, yoga, and other hodgepodge practices and philosophies, people are perhaps more primed than they have been in a while to consider what he’s offering.

Frankly, this line of thinking—and to know it’s again becoming en vogue—is refreshing, particularly in a city with crushing economic and social inequality. Even Foreign Policy argued in favor of it in a 2019 article, declaring, “French philosophy came to define the postwar era. As U.S. politics get ever more absurd, it’s time for a comeback.”

PARTNER CONTENT

We may have a harder time addressing the material comforts of every human on earth, but at least we can try to provide a roadmap for mentally riding the waves. Or, as Riggle puts it, “engaging in aesthetic life [is] a way of keeping in touch with the value of being alive.”