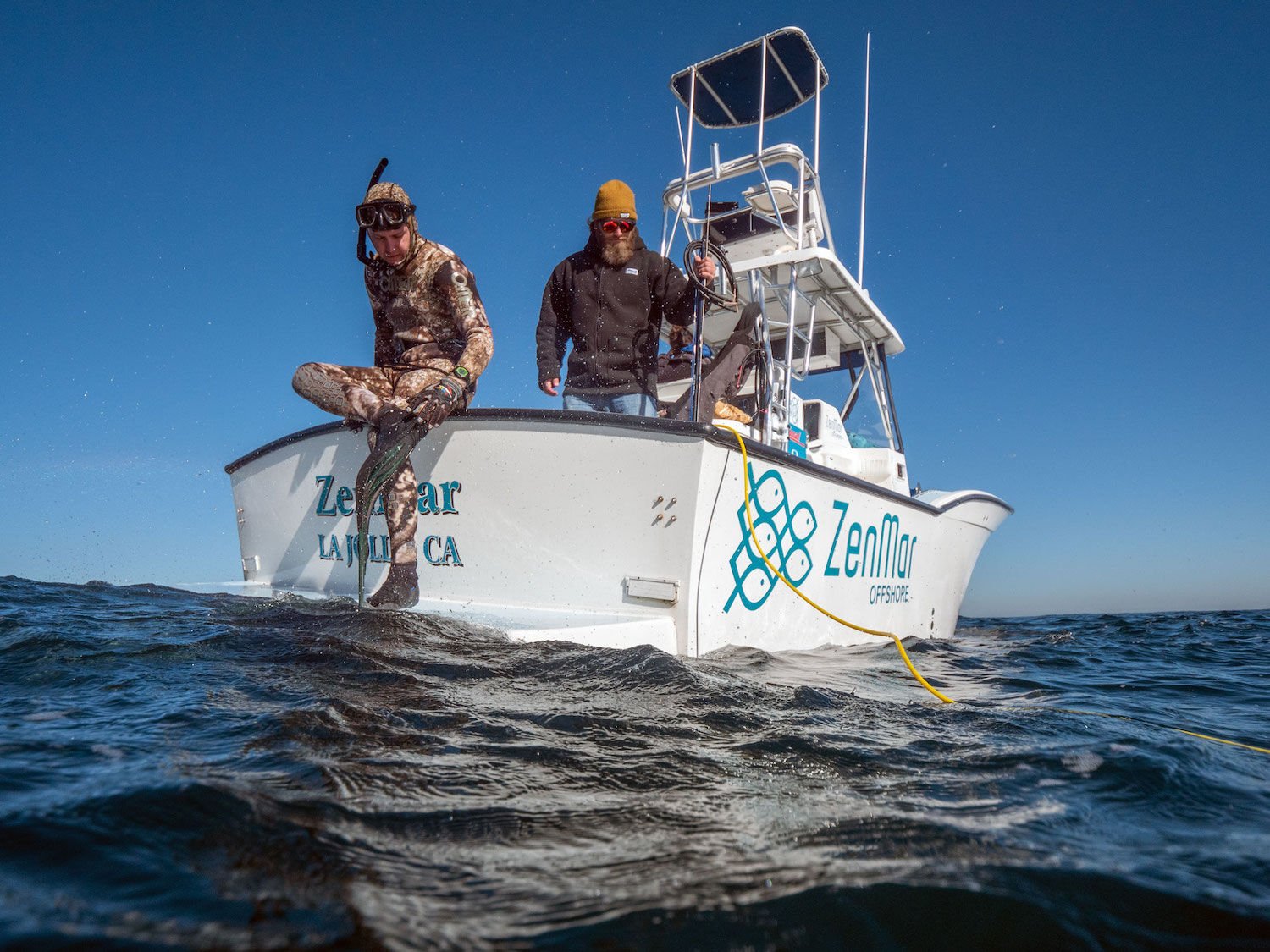

Spearfishing in San Diego, CA

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

Stepping off a boat into hazy green soup, one inevitably thinks of sharks. Is there one behind me, in front, or maybe to the side, just out of view? But a fishy sparkle soon shakes the fear away. I stretch back the rubber bands on my speargun and latch them into the shaft. I flick the safety off. It is a galvanizing reminder: I am the predator now.

Shortly before, on the boat approaching the Coronado Islands, 15 miles west of Rosarito, I felt like I was discovering a prehistoric world. The green, bright isles towered over a dark sea. I heard the bawl and cry of sea lions. I spotted countless seabirds, soaring serenely above or arrayed like sentries on cliffs painted fecal white. They watched us set anchor, bobbing in the blue.

“It’s like Jurassic Park,” marveled one of our boatmates, a marine biologist named Cassie Paumard. She squealed at the sight of shrieking sea lions as Chris Cheezem, our large, bearded captain, peered overboard. “Looks pretty green, but not terrible,” he said, guessing at the water visibility. The sun was shining. The wind was low. It was time to suit up.

There were two others aboard for this Tuesday morning jaunt into Mexican waters. They were Nathan Minatta, my guide, and a friend of Cassie’s named Alex. Alex had come poorly dressed, shivering in shorts on the ride over and slipping in his Reeboks. Only Nathan and I came armed. We were there to spear.

Spearfishing in San Diego, CA

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

A speargun is a simple, deadly instrument. It is fired by stretching thick rubber bands over the shaft and pulling the trigger. There are many different sizes and riggings. But the mechanics are most always the same: Rubber launches steel. Hopefully, you strike a fish.

I started spearfishing in 2020, searching for a quarantine-friendly hobby. At Second Chance Sports in Ocean Beach, I purchased a pole spear for $40 (pole, spear, rubber loop). I watched a lot of YouTube. Mostly, I dove: at Sunset Cliffs, Horseshoe, the Marine Room, Mission Bay. Eventually, I upgraded to a gun. The freediving aspect is the hardest part. Scuba tanks, while legal to use, are ridiculed by “spearos.” You get one breath.

The sport grabbed me in a way I hadn’t expected. But I’d been warned early on, while buying fins from Mark Morgan at the OB Spear Shack. “Get ready, man, ’cause this takes over your life,” he’d said, sounding like a cultist. But soon I became a believer.

The first spearos in San Diego were the Kumeyaay, who speared from land. Afterward came the Bottom Scratchers, a group formed in 1933. They are said to be the first-ever spearfishing club in the world. Wetsuits didn’t exist. Neither did spearguns, so they carried gargantuan tridents. Back then, monsters were easy to find.

Recently, wanting real training, I signed onto a Level 1 Freediving Certification course with Just Get Wet, a new outfit out of Mission Bay. It was founded in 2021 by Cheezem, an oceanographer and Navy veteran. The shop offers gear to buy or rent and also runs training courses and charters. Minatta, a towering, boyish man, was my instructor. A young, suave Angeleno named Melanie Chang was my only classmate (a third had opted out last minute due to a cut finger).

Spearfishing in San Diego, CA

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

Over three days, Minatta taught us the physics and physiology of freediving, proper form, and rescue techniques. It was a crash course in how to enter “fish mode,” as Minatta called it. Under his instruction, I accomplished previously unthinkable feats. During a static exercise in the pool, I held my breath for three minutes. The final day was a dive off La Jolla shores where we swam up and down a line hung from a small float. I reached 55 feet.

That might sound deep. But Minatta’s personal best took him over three times deeper: 180 feet in a Mexican cenote. Risk doesn’t seem to faze him. Once, he mentioned to me casually, he was charged by a great white shark while diving near Carlsbad Canyon.

Freediving can be dangerous. Some estimates put the fatality rate at one in 500—about the same as hang gliding. Each year, divers don’t come back. Natalia Molchanova, the designer of the training program used by Just Get Wet, is considered one of the best freedivers in history. In 2015, during a casual dive in Spain, she disappeared.

Minatta assures that, with proper training and supervision, freediving can be done safely. But certain precautions must be taken. Never recklessly push your limits. Never dive injured. Never dive alone.

Minatta, 35, started five years ago. He was raised far from an ocean in Fort Collins, Colorado. At the University of Colorado, Boulder, he majored in filmmaking. That was one reason Just Get Wet hired him. He produces dazzling underwater videos. But his instruction, infused with that warm flow of competence and easy articulation, is also superb.

Writer Brent Crane uses the “OK” sign to indicate to fellow divers that all is well.

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

As he often reminded us, to freedive well is to keep calm. During dives, every conceivable exertion, from tense shoulders to a wandering mind, needs to be minimized. The quicker your heart rate, the shorter your breath hold. In this way, it can feel like aquatic meditation. Om mani padme hum, you think, sinking into the abyss.

This tranquil aspect can seem at odds with spearfishing as a sport, which has a macho connotation. The San Diego spearfishing community, which is overwhelmingly male, certainly feels this way. That was one reason Cheezem started Just Get Wet. There were a handful of charters, shops, and clubs, but nothing that felt very all-encompassing or inclusive. Cheezem hopes to engender a larger community.

To that end, Just Get Wet hosts regular diving sessions and meetups. During my final certification dive off La Jolla, there were a dozen other divers, three of them women. Afterward, Cheezem—whom Minatta simply calls “Cheese”—grilled hot dogs and blasted ’80s rock. A strong sun warmed our wet heads. Divers sipped seltzers and chatted in small groups. In the San Diego way, there was no mention of work—only travel, tacos, and the sea.

This morning, diving this new, otherworldly site, I don’t feel like such a formidable hunter. Battling surge and current and cold, my breath-hold proves puny. Rammed about by waves, I feel as stealthy as a Tijuana zonkey. Leading the way, Minatta carries only a clunky camera, pointing out targets.

One of the rewards of spearfishing is the opportunity to eat what you catch. A California sheephead could become post-dive ceviche.

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

There are none for a while. Then, directly below us, he spots an ocean white fish. I take a breath and descend. My heart quickens as the animal floats my way. It is a good size, and I have a clean shot. My urge to breathe becomes unbearable. (This discomfort is the result of carbon dioxide building in the blood, not, as most assume, oxygen deficiency.) I pull the trigger. In a bubbly flash, the fish flees to safety. It is never fun to miss.

Hoping for less chop, we motor to the north island. The sea lions are more plentiful here, collected on rocks and crowded into their pristine bay. They bawl and jump and squirm like wild dogs. Cassie, the marine biologist, is ecstatic. Suiting up on the boat, she yips along with them. “Look, there are pups!”

This area is calmer, clearer, and more alive. Instantly, Minatta surfaces with a large California sheephead, a smiley, big-headed fish with a pink stripe. “For ceviche on the boat,” he says, almost apologetically. I am still catch-less.

Serious “spearos” forgo scuba tanks in favor of single-breath freedives. Requiring a slowed-down heart rate and a calm mind, the dives serve as a kind of aquatic meditation.

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

Sometimes a speared fish is killed on impact. This is called “stoning.” Most often, they survive and fight. Large pelagics like tuna and wahoo can take up to an hour to pull in. You let a fish tire itself out. The hunter floats above, pulling the thing closer by a long line attached to the spear. Once you have it by the gills, the fight’s over. The final blow is a knife between the eyes. This is called “braining.”

Minatta brains the “sheep.” As Minatta guts the fish with his fingers, its entrails float into the void. We continue for a while along the rim of the island, scanning every inch of reef. Minatta offers some advice. “Take longer rests on the surface,” he says “You’ll be able to stay under longer.”

We soon run into Cassie. She is overjoyed, floating near the reef surrounded by some 50 sea lions and holding out a GoPro. The happy pinnipeds become a constant presence for the rest of our dive, darting in and out of sight like the bats in Fear and Loathing. Occasionally one nibbles my gun. It is all unbearably cute. But it makes for tough hunting.

That is my excuse, anyway. They don’t seem to affect Minatta, who soon lands a fat calico bass, a brown, mottled rocket. He ties his two wins onto the front of his weight belt. Coronado sea lions are notorious for poaching divers’ fish. But they leave him alone.

Spearfishing in San Diego, CA

Photo Credit: Nathan Minatta

After a couple of hours, my descents become heavy and haggard. It is a small but bitter relief when Minatta announces it’s time to head in. In so many ways, spearfishing feels different from line-and-reel. But in this way, it is the same: You are not always successful.

That’s okay. It is a warm, bright ride home. We marvel at gray whales and pods of spinner dolphins that churn the sea white. Minatta makes ceviche with the sheepshead. We stab at it with tortilla chips standing up, trying to keep balanced.

Back at the dock, Minatta gifts me his calico. He won’t have time to eat it, he explains, and his freezer is full. In a couple of days, he’ll pack up his gear and fly to New Zealand, where he hopes to land a big yellowtail. (Kiwis call them “kingfish.”)

I thank him for his generosity and stash the fish in my backpack. But I am embarrassed by my poor performance. “Wish I’d shot one myself,” I admit.

PARTNER CONTENT

Cheezem butts in. “Hey, man,” he soothes. “A fish is a fish.”