To anyone paying only casual attention to Congress, Representative Darrell Issa, Republican from Vista, has been a Congressional terrier to the Obama Administration’s postal courier, dogging the President from the moment Issa became chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in 2010. Issa has spent four years holding hearings on everything from an IRS training fiesta at Disneyland to an attack at the U.S. compound in Benghazi, Libya, in which four Americans died. But while his committee could have delivered the kind of partisan red meat the Republican base craved, he developed a reputation for brash behavior and dramatic remarks that overshadowed his own hearings, blunting the impact of the revelations he was delivering. His term as chairman ended in December, and, by some reports, Congressional leadership was happy to see him go.

But when he isn’t chastising the executive branch and making headlines, another Issa emerges, a forceful advocate for government transparency, capable of working with Democrats and negotiating with the administration to pass open government legislation and whistleblower protections. In May, President Barack Obama signed the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act, a law that will expose federal spending in an online database, allowing Americans to know, for the first time, exactly how the federal government spends its money. Amid one of the least legislatively active Congresses of the last 60 years, Issa has advanced bills that will improve protections for whistleblowers, expand the Freedom of Information Act, and increase access for inspectors general. For a man who characterizes himself as ideologically close to the libertarian Cato Institute, and who said, “Congress has passed enough laws,” Issa is an impressive legislator.

An entire wall of Issa’s Capitol Hill office is dedicated to framed certificates of patents he has received, a legacy of his past in the electronics business. He is the richest member of Congress, having made his fortune selling car alarms to major automakers. Outside of politics, he may be best known as the recorded voice of Viper car alarms that orders would-be car thieves to “Please step away from the car.”

He launched himself into politics in 1998 when he ran in the Republican primary for California Senator. That bid was torpedoed by allegations of a shadowy past including an arrest, an indictment, and insinuations that he burned down one of his businesses for the insurance money. In 1999 he helped fund the recall of Governor Gray Davis. In 2000, he easily won election to Congress representing parts of San Diego, Orange, and Riverside counties. He has served seven terms in Congress and has never won by less than a double-digit spread.

When he arrived, he expected to serve on committees related to his business, like Energy and Commerce. “It never occurred to me to get on Government Oversight,” Issa says.

In 2003, retired Rep. Tom Davis, R-Va., the chairman at the time, recruited Issa to the committee. That year, Republicans held both the House of Representatives and the White House. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were already under way, and President George W. Bush’s popularity was surging. Issa believes the committee did some good oversight, but he also conceded there were plenty of stones left unturned in deference to a same-party president.

“There’s legitimate criticism, because in the two years Henry Waxman [D-Calif.] was chairman during the Bush administration [2007–09], time and time again he came up with areas we hadn’t pushed on that had merit,” Issa says. “The ground was pretty fertile. You had six years in which it wasn’t as aggressive as it could have been, and I think we all have to learn from that.”

In 2009, Obama took office and Edolphus Towns, D-N.Y., now retired, took over chairmanship.

“He didn’t have an aggressive bone in his body,” Issa says. “And we didn’t do anything.”

He planned to change all that.

“The Oversight Committee exists to secure two fundamental principles,” Issa intones from the dais at the start of every hearing. “First, Americans have a right to know that the money Washington takes from them is well spent. And second, Americans deserve an efficient, effective government that works for them. Our duty on the Oversight and Government Reform Committee is to protect these rights.”

The Other Darrell Issa

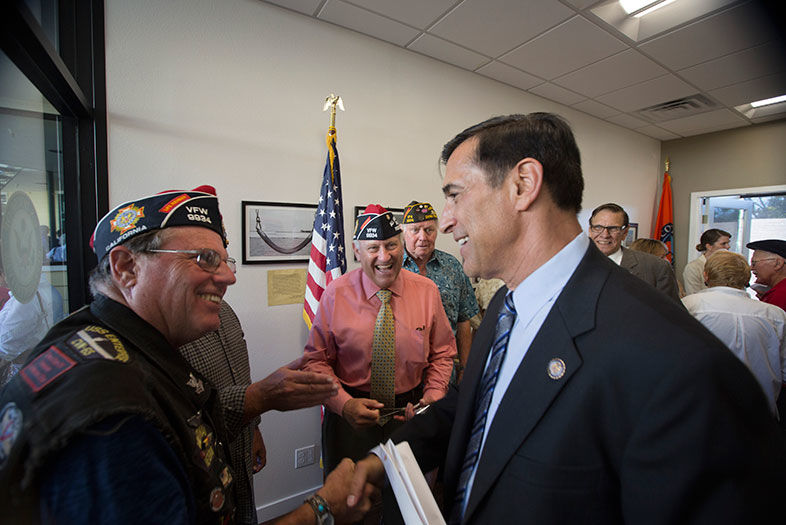

Rep. Issa opens a new Orange County office in Dana Point, September 3, 2013 | © All rights reserved by Congressman Darrell Issa

Rep. Issa opens a new Orange County office in Dana Point, September 3, 2013 | © All rights reserved by Congressman Darrell Issa

Issa began reciting this Law & Order-esque litany when he took over the chairmanship after the Republican wave election of 2010 as a way to give the committee direction. While other Congressional committees have oversight and budgetary authority over particular executive branch agencies, the Oversight Committee can issue subpoenas and launch investigations into nearly any subject, restricted only by the energy of its chairman and a willingness to fight turf battles with other committees. This broad mandate usually means that when different parties control the House and the presidency, the committee chairman is expected by his party leadership to score points on the administration.

In his time as chairman, Issa held 128 hearings (though he held more in the lame-duck session that started after Election Day). Of those, he dedicated 30 to government waste, while 14 were dedicated to the Affordable Care Act; 13 to the EPA; seven to the Fast & Furious scandal, in which the Justice Department allowed criminals to buy guns in the hopes of tracking them; 11 to the IRS; four to Benghazi; and three to Solyndra, a failed solar company backed by federal loan guarantees. Issa does not lack for aggressive bones.

Issa’s staff members point out the successes: Hearings on a sweetheart loan program for important personages led to an ethics investigation into loans received by four members of the House (three Republicans, one Democrat); the hearings on Fast & Furious led to a (largely partisan) House vote censuring Attorney General Eric Holder, the first censure against a sitting member of the cabinet. Revelations of partying by the IRS revealed no fraud, but motivated the IRS to cut spending on training by 80 percent, an inspector general report said. And hearings on whether the IRS office in Cincinnati targeted Tea Party groups for further scrutiny led to the resignation of Lois Lerner, an IRS official responsible for exempt organizations.

Yet for all the sound and fury, a common critique of Issa from the D.C. political class is that he hasn’t wounded the President in a significant way, or that he has taken the focus off the issues and turned it to himself.

“Issa tends to get in the way of issues that could really energize the base,” says Norman Ornstein, a resident scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

In February 2012, as Obama labored toward re-election amidst a struggling economy and weak poll numbers, Issa seized an opportunity to galvanize the Republican base with a hearing on whether Obamacare mandates related to birth control infringed on religious liberty. Of 11 witnesses called by the committee, nine were men, including the first panel heard. The move helped the Democrats paint Republicans as anti-woman.

“I’m sure he’d like to have that one back. That was bad optics,” says Davis, the former committee chairman.

In March, Issa became the center of attention when he abruptly adjourned a hearing on the IRS targeting scandal. Lois Lerner, the IRS official, opted to take the Fifth Amendment in the midst of questioning by Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland, the ranking Democrat on the committee. Issa abruptly rose and adjourned the hearing, ordering staff to turn off the audio. The visual impression of a tall white man silencing an older black man was not lost on the Congressional Black Caucus. It demanded that House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, strip Issa of his chairmanship and require Issa to publicly apologize.

“Mr. Issa is a disgrace and should not be allowed to continue in a leadership role,” Rep. Marcia Fudge, D-Ohio, chair of the caucus, wrote in a letter to Boehner.

Issa did apologize to Cummings, and the House never took up the censure. Cummings would later offer his own retort in the form of a minority report accusing Issa of using the same tactics as those used by Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

When asked to describe his present relationship with Issa, Cummings, who had once had a productive legislative relationship with Issa, issued a statement more notable for what it didn’t say: “The Oversight Committee has tremendous potential to improve the everyday lives of Americans, and I sincerely hope that whoever holds the chairman’s gavel—Republican or Democrat—will work on a bipartisan basis to develop constructive reforms.”

The mistakes and distractions have led some observers to think Republican leadership was growing frustrated with Issa. Last spring and summer, stories from Politico, Roll Call, and Breitbart.com all reported friction between Issa and House leadership, though none contained direct quotes offering an outright criticism.

“I’ve spoken to leadership staff; they’re frustrated with him,” Ornstein says.

In May, Speaker Boehner announced there would be a special committee to investigate the deaths of Americans at Benghazi on September 11, 2012, adding fuel to the idea that Issa had lost the confidence of top Republican leaders. On November 21, the House Select Committee on Intelligence produced a report saying, in essence, there was no “there there.” It cleared CIA officers working in Libya of any wrongdoing and said their “actions saved lives.” A spokesman for the Select Committee on Benghazi said the committee would review the report.

A common critique of Issa is that he has taken the focus off the issues and turned it to himself.

Issa says he has a solid relationship with House leadership, calling Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., a dear friend. He said the move on Benghazi was simply the resolution of a turf battle between himself and other committee chairmen who wanted control of the hearings. He cast the move as a victory for his view that Benghazi had been an administrative failure.

“The select committee ultimately is a huge win for a determination that there really is a there there,” Issa says.

In November, as Congress prepared to go back into session after five weeks spent running for office, Issa managed to get back in the headlines twice just days before he ran one of his last Oversight hearings as chairman of the committee.

At a November 6 book party for former reporter Sharyl Attkisson, Issa said his committee relied on driven journalists to get word of the committee’s investigations out to the larger public. Without them, his committee “is a desert island.”

“When an administration says ‘no,’ it’s no different than when Andrew Jackson marched Indians down the Trail of Tears, to their death,” Issa says, according to reports in Politico and Bloomberg Politics. “The fact is, the government will obey the administration’s orders, if there isn’t somebody to say ‘Hold it, stop!’”

The titters and outrage from that gaffe had hardly diminished before Issa again became the center of attention, thanks to a social media stunt gone awry. Issa, or whichever staffer runs his Twitter account, offered to retweet pictures of family members who served in the military in honor of Veterans Day, according to the Daily Dot. The bait proved too sweet for trolls to resist, and Issa’s account soon retweeted images of Heinrich Himmler, described as “my late grandfather,” and Lee Harvey Oswald, described as “Uncle Lee,” among other

villains of history.

Issa’s then-upcoming hearing on abuse of telework by officials at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office had become an afterthought.

Hudson Hollister, now the executive director of the nonprofit Data Transparency Coalition, had just resigned his job at the Securities and Exchange Commission on the day in 2009 that he marched into Issa’s office, resume in hand, to ask for a new gig. At the SEC, he’d been laboring to persuade his superiors to standardize and digitize their data collection activities to improve transparency, but to little avail. He told Issa he thought the whole government should make its information available online. Issa hired him.

“We wanted to move the government from documents to data,” Hollister says.

While switched-off microphones and accusations of sexism and government fraud make for the kind of melodrama that attracts attention from the press and the public, they are also the kind of white noise that tends to fade over the long history of Presidential–Congressional relations. Issa’s most lasting legacy will likely be shepherding through Congress laws intended to improve government oversight.

Hollister knew Issa had a technical background that might make him receptive to a digitization pitch. Issa knew computers. He said he learned to program both COBOL and FORTRAN, and in an interview he tossed off a programming joke about “Do Loops.” He realized the potential of digitizing government spending data after witnessing the success of Recovery.gov, a website that tracked spending from the stimulus appropriated under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

The Other Darrell Issa

Haircut in the Senate Barber Shop on April 24, 2013 | © All rights reserved by Congressman Darrell Issa

After taking over the Oversight Committee, Issa had a platform from which to push the issue. In consultation with now-ousted Majority Leader Eric Cantor, R-Va. (“A dear friend, I miss him”), Issa proposed a bill that would standardize and digitize all government documents. But with Democrats in control of both the Senate and the presidency, he would need collaborators to get it done.

To help the bill in the Senate, he linked up with Virginia Democratic Senator Mark Warner, a fellow former businessman and the wealthiest man in the upper chamber, and he later pulled in Republican Rob Portman from Ohio. The heaviest opposition, though, came from the White House Office of Management and Budget, which until this bill, was one of the few organizations that actually possessed spending data.

“There was a lot of palace intrigue within the Administration in the years-long fight over the DATA Act—not ideological, not Republican versus Democrat—but deeply entrenched figures in the White House’s Office of Management and Budget and other places that had been there before the Obama Administration and will be there after they leave,” Issa says.

Moving the bill would require numerous modifications, including lowering its sights from all government documents to just its spending, but in May President Obama signed the DATA Act into law.

The DATA Act does not stand alone among Issa’s legislative achievements. Issa views whistleblowers, people deep in the operations of a business or federal bureaucracy who spot wrongdoing, as an essential element of transparency. He guided through Congress the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act of 2012, a bill that expanded protections for federal talebearers, particularly those in the national security or intelligence communities.

In 2013, Issa attached an amendment to a House operations appropriation bill that would require the chamber to publish bulk data on the legislative process in an easily accessible format, a long-held desire of open government groups. He later withdrew the amendment, but House leadership changed operations and began publishing the data.

“My view is that to eliminate the big problems in government in the way of waste and fraud and abuse of power is to give the most federal transparency to the entire world,” Issa says.

Hollister would later leave Issa’s employ to start his own nonprofit explicitly to provide outside pressure for the DATA Act’s passage and implementation. While many congressional staffers leave government for high-paying private sector jobs, Hollister and two others of Issa’s recent staff have founded nonprofits dedicated to government transparency.

Republicans limit their members to six years as senior representative on any given committee. Issa spent two years as the Ranking Member of the Oversight Committee, and then four years as its chairman. He expects to hold a senior role on the Judiciary committee, but it’s not clear what the future is for his Congressional career. When Cantor lost his primary election earlier this year, Issa was not part of the conversation for the newly freed-up leadership roles.

Now that his time running the committee has ended, Issa is less focused on what he did or did not accomplish than he is on finishing the work he started: Implementation of the DATA Act and getting the Senate to pass a reform to government information technology spending and improvements to the Freedom of Information Act, among others.

His passion for opening up government remains.

“Every generation has to have people who do the job that I’ve been honored to do,” he says. “The moment government can sweep things under the rug, the first thing they sweep under the rug is a waste of your money; eventually what they’re sweeping under the rug is an NSA project that’s controlling everything, including elections.”

He adds later: “Since our founding, unnecessary secrets have caused the American people to be cheated by their government, out of their liberty and out of their money. That is the transparency that is most important to me.”

The Other Darrell Issa

PARTNER CONTENT

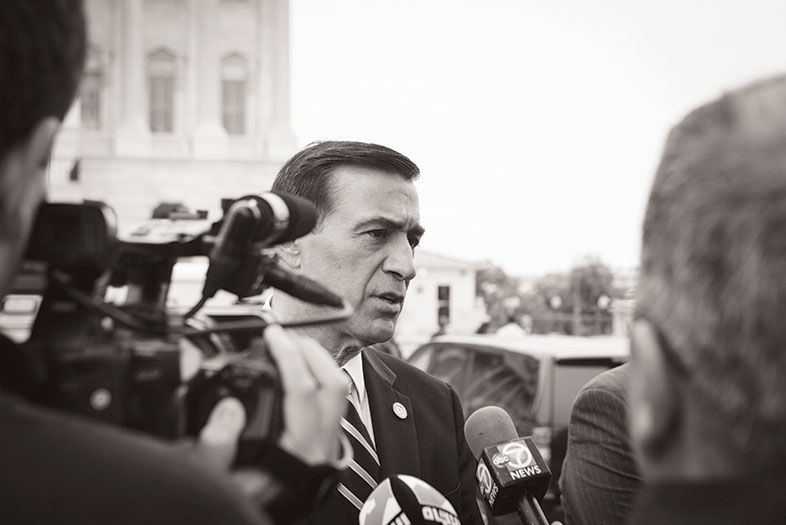

Darrell Issa, October 9, 2013, Washington, D.C. | © All rights reserved by Congressman Darrell Issa