For an entire year, Scott Fitzgerald couldn’t feel his pulse. The Vista resident, now 51, had a high-tech heart pump that continuously pushed blood through his body. “There were times when I was lying in bed with my ear on my arm, and I could hear the pump humming. Now,” he says, having received a heart transplant last fall, “I can do the same thing, but I hear my heart beating.”

In 2000 at age 33, Fitzgerald endured six rounds of chemo and six weeks of radiation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. “I was told there would be side effects to chemo—there are side effects to every medication you take,” he recalls. “At the time, I was like, ‘If I don’t survive cancer, it doesn’t matter if my heart’s not working.’ You’re kind of in that position. You’re like, ‘Let’s do the treatment.’ And I didn’t even think about it after that.”

He went into remission, and for 12 years he was in the free and clear, with no reason to worry about further side effects—until one day he couldn’t get past a half mile of an eight-mile walk without feeling out of breath. The doctor told him he had a heart problem and was retaining water. Meds and diuretics helped him manage, but things got worse with time. “I couldn’t walk 100 yards. They found out it was cardiomyopathy, probably due to chemotherapy.”

A Change of Heart

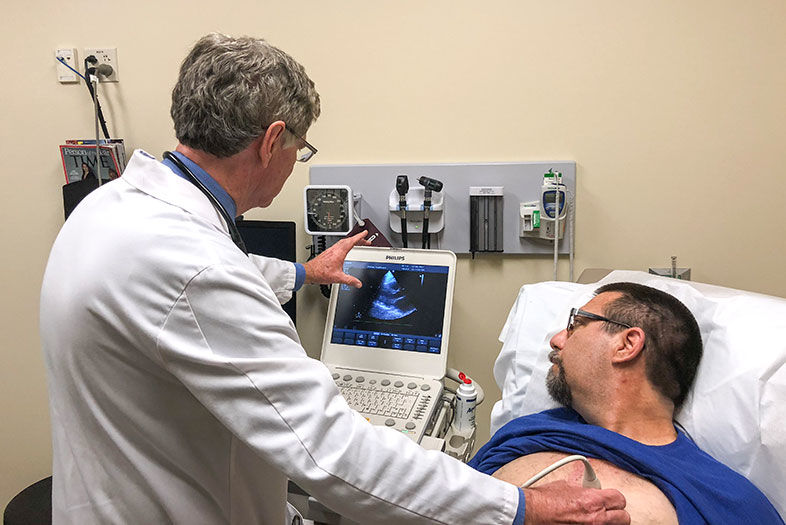

Scripps Clinic cardiologist Thomas Heywood, MD, using an ultrasound machine to examine Fitzgerald’s heart

For the next four years, he tried to get in shape but was in and out of the hospital. Finally he agreed to get a pump implant called a left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, at the Prebys Cardiovascular Institute, part of Scripps Memorial Hospital La Jolla.

“The LVAD allows us to save patients,” says Dr. Thomas Heywood, director of the heart failure program there and at Scripps Green Hospital. “We don’t have enough hearts to do transplants—maybe only 2,500 a year. If you can’t get a transplant, or you’re so sick that you’re dying, like Scott was, we can put in an LVAD and do a transplant when the patient is better. The LVAD can be an end in itself for certain patients, or it can be a bridge to a transplant.”

For Fitzgerald, it was the latter. But in order to qualify for the transplant list, he had to have a body mass index of 35 or lower, and he struggled to lose weight because the LVAD limited his energy. It took him about a year—and one gastric sleeve operation—to get on the list.

It was September 2017. He expected to wait on the list for two to three years—maybe six months at the very least. Just 10 days later he got a call.

Protect Yourself

Between 50,000 and 100,000 people die every year of advanced heart failure.

- Get regular blood pressure checks.

- Keep your weight stable.

- Don’t smoke.

- Know the warning signs: If you’re short of breath when you walk or climb stairs, or you have swelling in your legs, see your doctor. Noninvasive tools can detect whether it’s a problem.

“A nurse from Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles called at 2:30 in the morning and said, ‘We have a heart for you.’ They told me I had to be there in four hours.

“I was shocked. In total amazement. I kept saying, ‘Really?’” He grabbed his pre-packed bags and sped off to LA.

His heart comes from a 20-year-old man, and that’s all he knows for now. After a period of one year he will be allowed to request contact with the donor’s family, who can decide whether they want to speak with him or even meet him. “I definitely will reach out. Donating is a gift that you can give anyone that needs it.”

In fact, a single tissue and organ donor can save up to eight lives and heal as many as 75. “Donation is healing, not only for the transplant recipients, but for the donor families as well,” says Lisa Stocks, executive director of Lifesharing, an organ and tissue donation nonprofit. “They take comfort knowing their loved one lives on—and they’re proud that their family member became a lifesaving hero.”

A Change of Heart

Fitzgerald with his mother in 1999 when he was being treated for cancer

In the meantime, Fitzgerald has become a very healthy cook and consummate walker, aiming for a minimum of 15,000 steps a day. He likes walking at Daley Ranch in Escondido and on The Strand near Oceanside Pier.

And now that he’s no longer waiting for a phone call about a donor heart, he’s free to travel. “I think Ireland would be a nice place to go,” he says. As for other bucket-list items? “Maybe I’ll jump out of an airplane; I don’t know yet. I just became alive again.”

One activity he spent no time contemplating was volunteering time to talk to hospital patients awaiting an LVAD. “I give them my point of view, because the doctors can’t really tell you what it’s like. I’m more than happy to spend hours talking to them. I feel like I have to give back somehow.”

“There’s a lot of hope in this area; we can save most of the people that we take care of,” says Dr. Heywood. “And we can do a lot more now than we could even five years ago. I wouldn’t do this work if patients didn’t get better. I tell people I want their heart problem to be their hobby and not the center of their lives, so we work very hard to give them their lives back.”

Have a Heart

Reasons to register as a donor

2,000+ people in San Diego and Imperial counties are waiting for an organ

80 San Diegans died last year waiting for a donor

21,000+ Californians are on the waiting list, more than any other state

8 lives can be saved (and 75 more people healed) by one person donating organs and tissue

88% of people waiting in SD and Imperial counties need a kidney; 9% a liver; 3% a heart, pancreas, or lung

Register to be a donor at lifesharing.org

Source: Lifesharing / Donate Life San Diego

A Change of Heart

PARTNER CONTENT

Fitzgerald with his heart surgeon and nurses at Scripps Memorial Hospital La Jolla in 2016 after he was implanted with an LVAD