I take the winding, country road from my hometown of Seville, in Andalusia—the southernmost region of Spain—to the mountain range known as Sierra Morena. I’m here to find out more about Saint Diego, the namesake of the city where I’ve lived for almost a decade, some 5,000 miles away.

This road is as familiar to me as the 79 to Julian, the narrow curves peppered with childhood memories of driving up here on the weekends. Hundreds of cork and holm oaks, not unlike the ones in southern California, line the road. It rained recently, so the soil is covered in grass and wildflowers, but I know that underneath, there is clay-like red earth that’s soft to the touch. Bulls graze lazily, swinging their tails to scare flies away.

Eventually, I arrive in San Nicolás del Puerto, a small village of white houses beside a river with a Roman bridge. Around 600 people live here regularly, with the population increasing in the summertime. It’s not the prettiest or the most romantic of little Sevillian mountain towns, to be honest with you. But one thing brings me to these rocky hills of my ancestors: Saint Didacus, also known as San Diego, was born here in 1400.

When one enters the small town, the imprint of San Diego—the man—on the lives of its inhabitants quickly becomes obvious. The local school, one of the streets, and an hermitage (a small place of worship) are named after him. There are pictures of his likeness on the street. Businesses bear his moniker in big, bold lettering.

I ask passers-by how to get to the hermitage, and they refer me to a small supermarket called La Alacena, owned by the Eldest Brother of the First Brotherhood of San Diego. He’s busy working behind the counter, but he directs me to the person who helps maintain the brotherhood’s assets, 70-year-old Ángela Gómez Macías.

There aren’t many historic accounts of what San Diego’s life was like in his youth. Most internet articles say his origins were humble and pious. One can imagine, while walking down the orange tree–lined streets of this mountain town, that life here in the 15th century couldn’t have been very luxurious. According to the San Diego History Center, “as a young man, [San Diego] lived as a hermit and practiced asceticism prior to joining the Order of St. Francis of Assisi.”

But first, he was baptized at San Nicolás del Puerto’s 15th-century-era San Sebastián Church, a small but pretty Mudéjar-style chapel with a clock tower where a stork has made its spring nest. Gómez Macías shows me the ancient-looking baptismal font. She was baptized here, too, along with almost every child in the village.

A tile painting behind the font depicts San Diego in his Franciscan robes. Between the folds, he hides flowers. It’s a reference to one of his alleged miracles, the reason for his elevation to sainthood. Legend says that, one day, San Diego was sneaking away some bread to feed the poor, which was frowned upon in his order. The custodian friar of his monastery asked what he was hiding. The bread turned into roses. Showing the blooms to the surprised monk, San Diego walked away. The flowers transformed back into loaves again, and he passed them out to the beggars.

“San Diego means a lot to me—look,” Gómez Macias says, pointing at her arm, where her hair stands on end as though she has goosebumps. Some see raised hairs as a signal of devotion.

We walk two streets down and visit the house where San Diego was born, according to the plaque on its façade. There’s nobody to open the door for us, but we peek through the window and spot a donkey hanging out in the backyard.

We drive a mile outside of town to the hermitage, where a likeness of San Diego—a life-size wooden statue—presides over the space. “He’s very pretty,” Gómez Macías points out. “He’s beautiful.” She tells me he’s always represented carrying the wooden cross he’s said to have died clutching. On his shoulder perches a bird.

An hour or so later, Beli Gómez, a fellow patron at one of San Nicolás del Puerto’s three restaurants, offers an explanation for the avian companion. It’s a story she heard many times from her mother: “[San Diego] loved animals, and his father had a lot of birds in captivity, and he used to open all their cages and free them,” she says.

Beli confesses she’s an atheist. I am, too, but in Andalusia we don’t need to believe in miracles or God to love our saints, sacred statues, and rituals. Do you need to surf to love southern California’s beach culture?

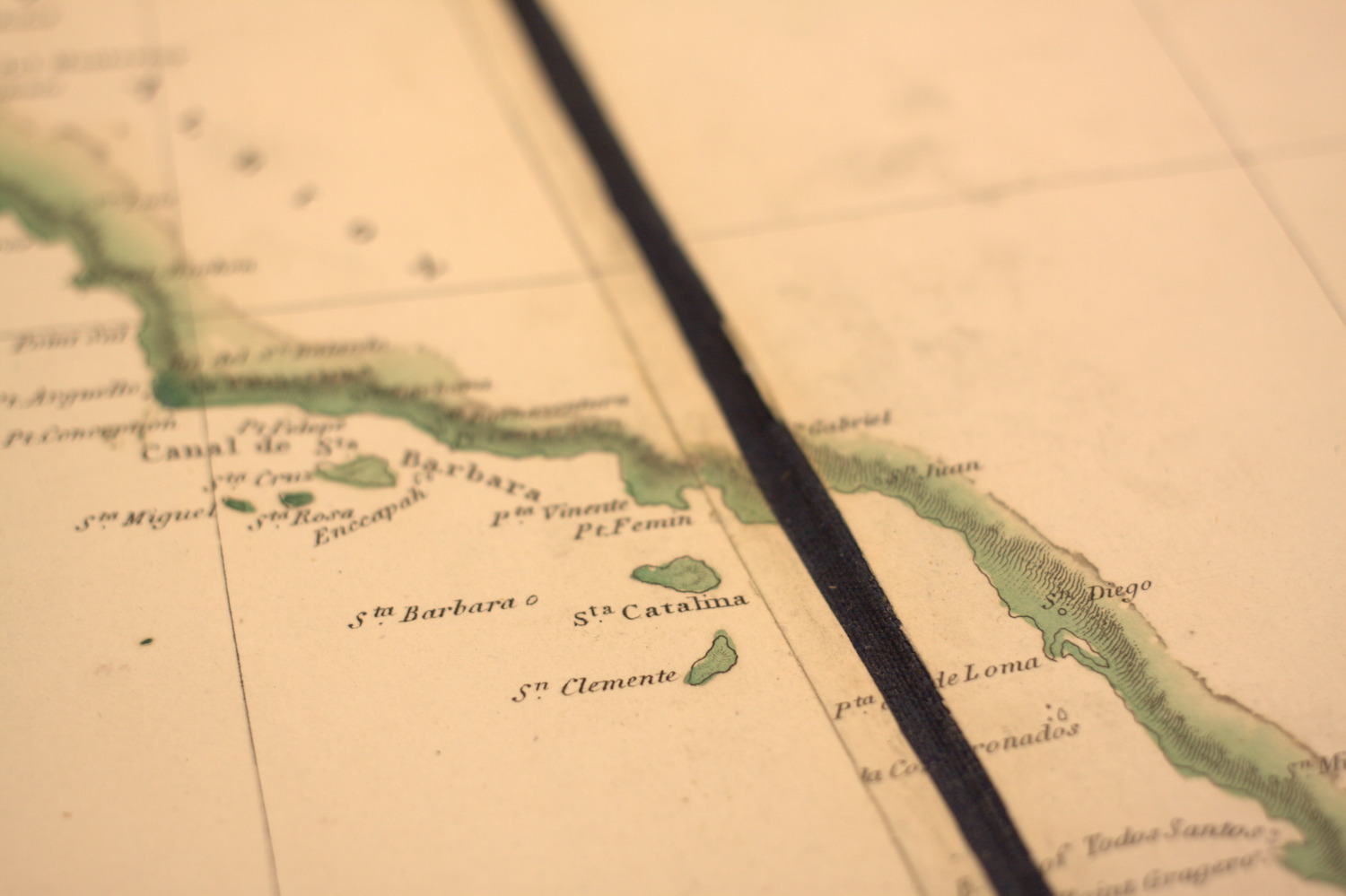

According to the San Diego History Center, it was cartographer Sebastián Vizcaíno who named the San Diego Bay in 1602, even though Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo had already visited the spot in 1542 and dubbed it San Miguel. It was the second European name that stuck. San Diego himself never set foot in the Americas—he died in 1463, nearly 30 years before the first of Columbus’s expeditions left from Huelva, 125 miles away from San Nicolás del Puerto. I arrived in the saint’s namesake city more than five centuries later, in 2015.

As I drive down the mountain, I think about all I had to change, all I had to become, to fit into my Southern California life. All the pieces of my Southern Spanish soul that I had somehow misplaced, forgotten in a dusty corner of my single-story, mid-century-modern, single-family home.

I feel like finding Saint Diego has helped reintegrate some of those pieces I had lost. The Andalusian and the Californian. My roots and my present, all put together in a saint who turned bread into flowers.

When I tell Gómez Macías I live in San Diego, California, her face doesn’t register surprise, but she admits it’s her first time meeting someone from the town named after the saint. It’s apparent that even though the lives of many residents of San Nicolás del Puerto are touched by the namesake of our city, they don’t much care that a town on another continent is named after him.

To me this seems like such a crucial moment, connecting the dots of this strange coincidence that I have ended up in a town so far away from my ancestral land, and that yet it carries the name and the faith of these people, who are more like me than perhaps anyone I’ve met in San Diego.

In the nine years I’ve lived in San Diego, it’s been hard to feel like it’s my home, in a way—even though I birthed two children and bought a house in the city. I’ve always felt a much stronger sense of belonging in southern Spain, where my heart pulses in time with the beats of flamenco, people understand my accent, and it doesn’t take a five-minute conversation to explain my name.

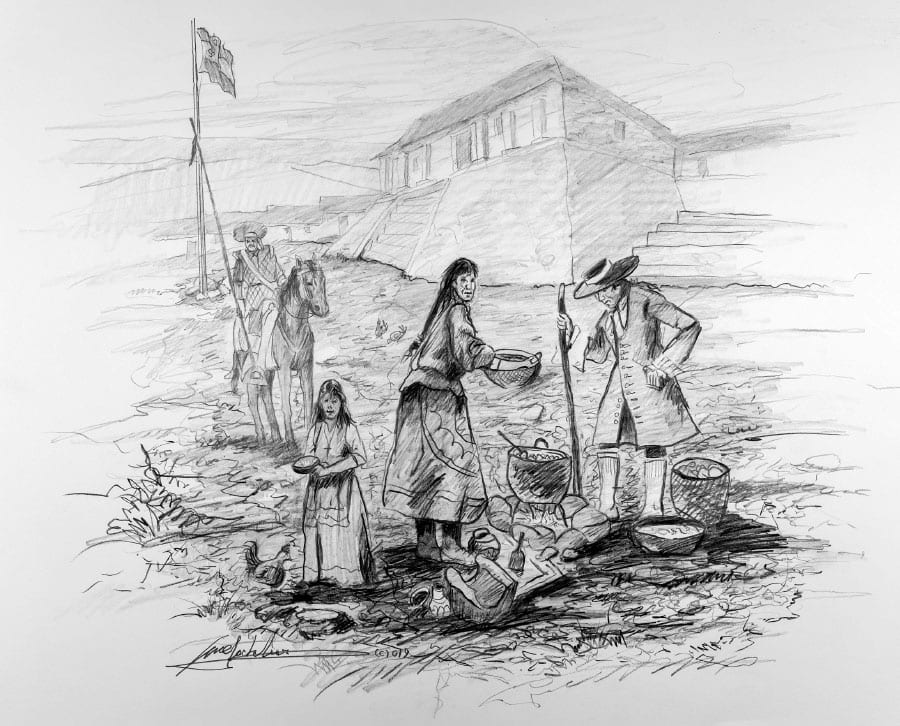

It’s also difficult to reconcile the fact that people who came from the same place as me not only gave San Diego county its name, but played a big role in the despicable acts committed against the region’s first inhabitants, the Kumeyaay.

I feel torn between pride in my culture, my roots, and where I come from and embarrassment and rage for what people from my country did to others. We need to do way better at communicating our colonial history so it doesn’t repeat.

Because just like not knowing where the name of San Diego comes from can keep us from an interesting piece of our past, not facing the history of those who came before does our city, our country, and the world a disservice.

“How can a town named San Nicolás del Puerto,” Beli muses, “not have a puerto (port) or a saint named Nicolás?”

“How can a town named San Diego,” I think to myself, “be named after a cult that originated 5,000 miles away, and of which its citizens know nothing about?”