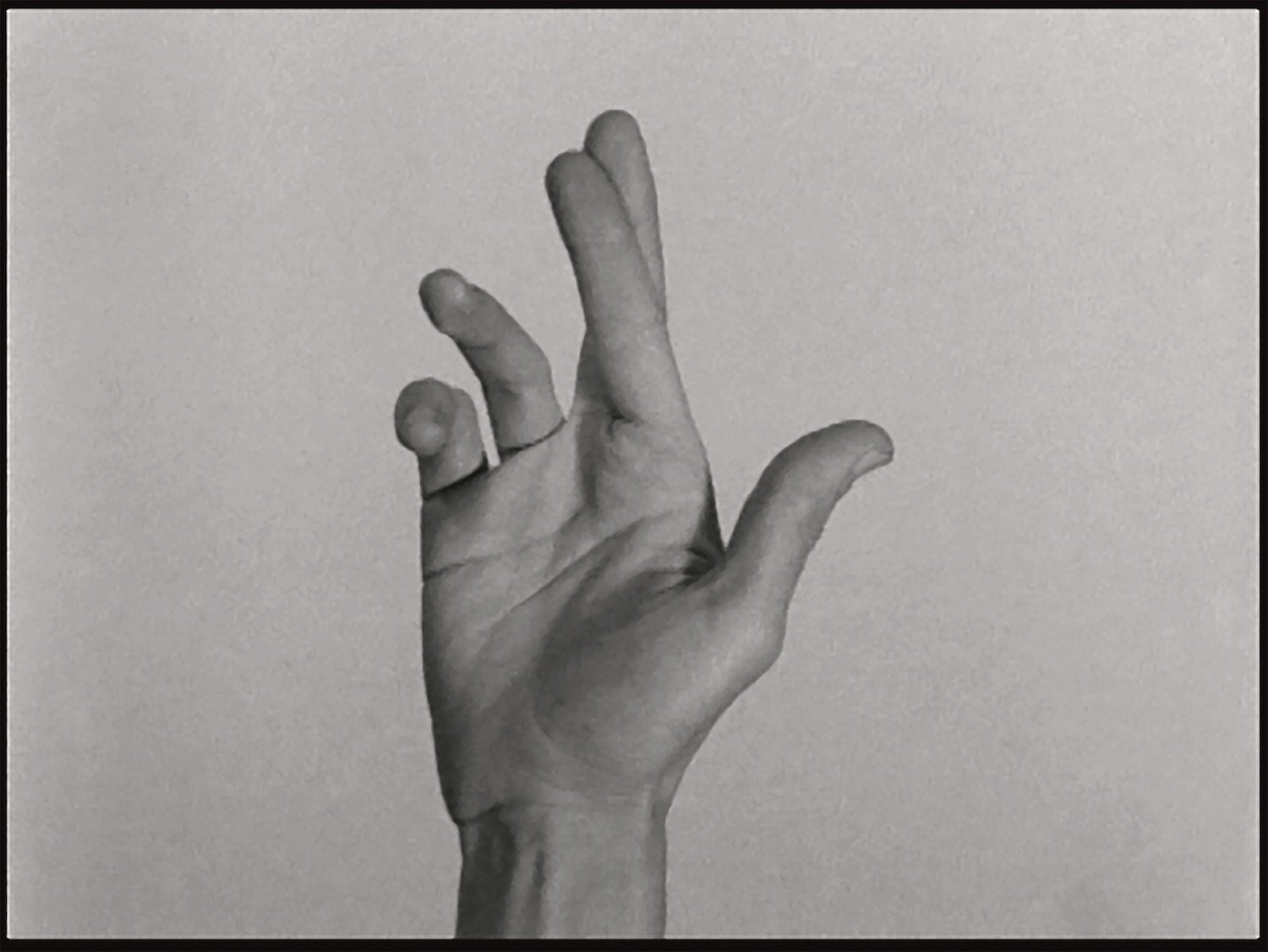

The twitch of a finger. The twist of a palm. At first, it looks like a hand simply moving in space. But then you see it for what it is: a dance. These are the rhythmic, deliberate maneuvers of choreographer Yvonne Rainer, filmed in 1966 as she recovered from surgery in a hospital bed.

This dance welcomes visitors into the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego’s For Dear Life, an examination of illness and disability on view into February 2025. The show is part of PST ART, a Getty initiative bringing together over 70 institutions to mount exhibitions themed around the relationship between science and art.

A Still from Yvonne Rainer’s Hand Movie (1966)

Featuring more than 80 artists, For Dear Life is the first survey of its kind since the 1960s. It follows “what some people talk about as a kind of second wave of the disability rights movement, often referred to as disability justice … and a surge of work being created around themes of illness and disability since the Covid pandemic,” says MCASD Senior Curator Jill Dawsey. But the exhibition, which spans decades, proves that artists with disabilities have always been here, producing pieces that probe the limitations and possibilities of their own bodies and minds.

The show takes an expansive approach in defining its central subjects. “We all fall ill. We all will become disabled, if we aren’t already. Disability is a category that applies to a quarter of the US population,” Dawsey says. “[It] is a thing that touches everybody.”

Grouped by era, the showcase begins in the mid-’60s, when feminist artists began to push the boundaries of what was considered worthy of scrutinizing in art. “[They were] making work about the vulnerable body, the unruly body,” Dawsey says.

An untitled 1977 work by Milford Graves

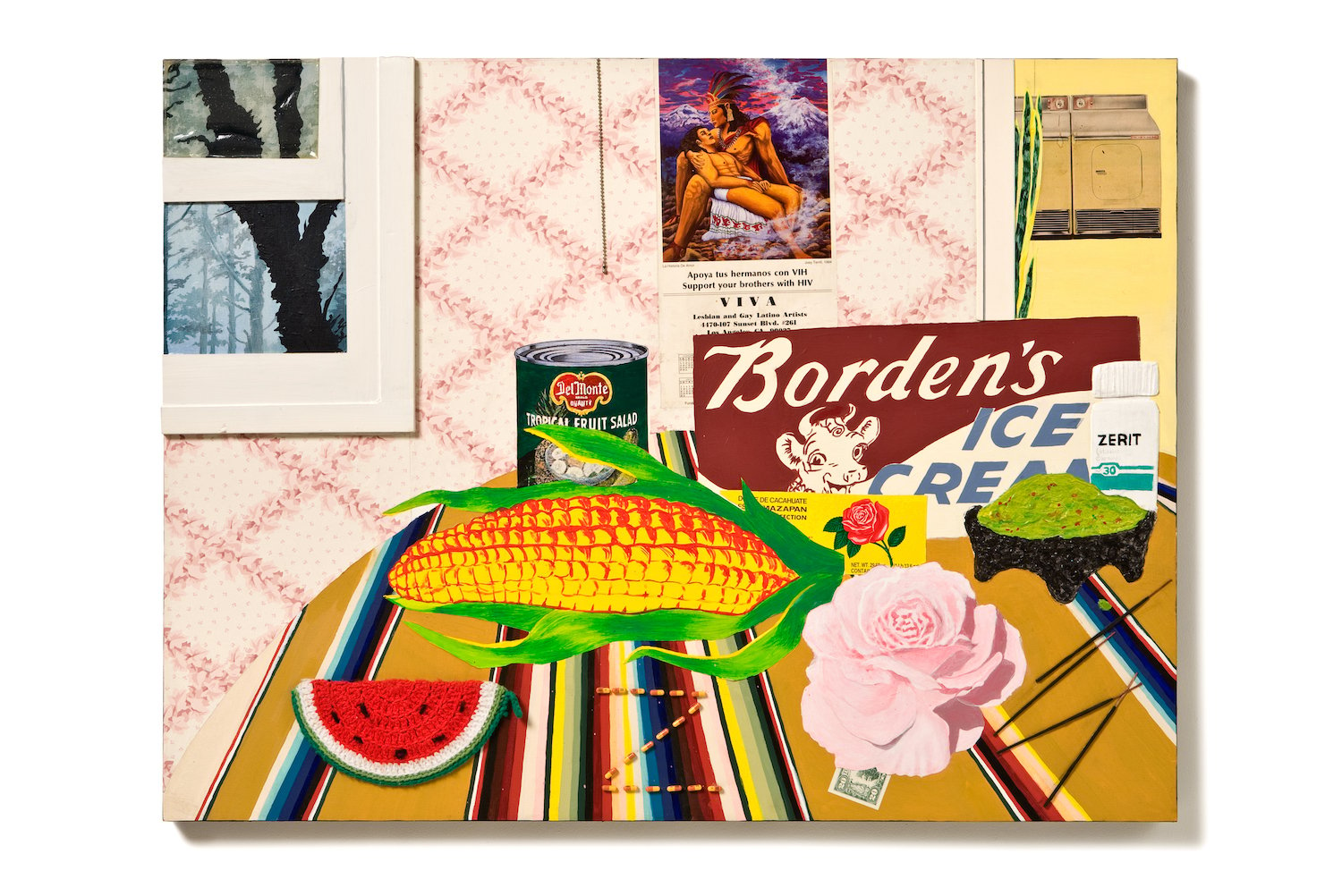

Then came veterans’ explorations of the impacts of the Vietnam War in the ’70s, and, in the decades after, the work of those affected by the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

Pieces confronting substance use disorders bring context to the War on Drugs. Some link the use of pesticides in agriculture to illness and death. Others reference the Black Panthers’ community healthcare clinics in the mid-20th-century.

The result is an exhibition that resists the pressure to reduce social movements into bullet points on a timeline. Instead, it reminds the viewer that the waves of history always pass over the body, often to devastating effect.

Indeed, embodiment is core to the show, even as its more abstract works offer alternative ways to imagine corporality. In a piece by Senga Nengudi, spiky cones of clear vinyl filled with dyed water stretch across the gallery floor, evoking both sterile IV bags and limbs or organs, something illegible and alive.

Richard Yarde’s 2001 work Ringshout: Mojo (Mojo Hand III)

In another, Richard Yarde’s Ringshout: Mojo, the watercolorist’s palm prints form a circle on the massive, 90-by-90-inch canvas. “His body enters the practice in a different way,” Dawsey says. “Even though he’s not representing his whole physical form, you have this large sense of the artist being in the work and moving around the work.”

Mobility aids and prosthetics also stand in for—or expand definitions of—the body (a placard under filmmaker and activist Ray Navarro’s photograph of a cane reads “THIRD LEG,” while a wheelchair is labeled a “HOT BUTT”), and many featured artists approach them and other aspects of living with disabilities with a wry humor—and a powerful sense of ingenuity.

Take Rainer’s Hand Movie, the way it distills and compresses choreography to create a form of dance that feels wonderfully strange and new. Or Sandie Yi’s Crip Couture series, which, as Yi wrote in a 2020 manifesto, “uses wearable art as a medium to articulate new meanings of disability.” Painter Katherine Sherwood’s work shifted after she experienced a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 44 and, with her dominant hand paralyzed, relearned to paint with the other.

PARTNER CONTENT

Joey Terrill’s Still-Life with Zerit (2000)

So often, stories about artists with disabilities center around them “overcoming” or “triumphing” over their impairment, language “that implies that [not being] disabled is the better and more normative position,” Dawsey adds. For Dear Life offers a different perspective: Disability as an impetus for creativity and innovation.

“It can really transform artists’ work,” Dawsey says. “It becomes a catalyst for developing new processes and new subject matter and new politics. Illness and disability are actually very generative.”