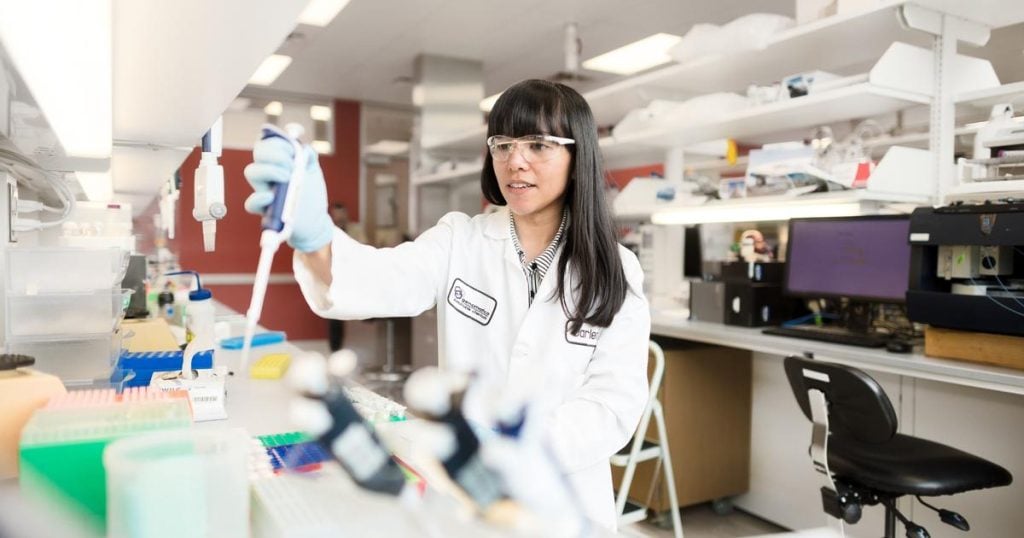

After 10 years, Christophe Schilling was ready for his company, Genomatica, to pivot. He launched the brand in 1998 as a bioengineering PhD student at UC San Diego, with the original idea of using computer models to study metabolic engineering in single-cell organisms.

But even with a decade of investment, he elected to change course. Instead of focusing on a small aspect of the metabolic process, Schilling wanted to use the computer-modeling techniques he’d developed to replicate the ingredients used in everyday things like soap and fabric.

The reason? Ninety-six percent of those materials come from chemicals made using fossil fuels. They are one of the leading drivers of carbon emissions. His idea was to make manufacturing more sustainable by substituting those products with industrial sugars like corn, sugar beet, and sugar cane—and to do it so effectively that the companies wouldn’t notice the difference in either their manufacturing process or their final products.

At the time, other companies were using biotechnology to go after the emerging biofuels markets, but Schilling wanted his company to focus on the high-volume chemicals that make up our clothes, cleaning supplies, shampoos, even carpets.

It looks like the right call. Today, the San Diego–based company boasts partnerships with everyone from Cargill to L’Oreal to Lululemon.

It’s all thanks to their innovative tech. Genomatica specializes in what they call “drop-in materials,” a product that can be “dropped in” to a company’s existing manufacturing process. “It shortens the amount of time that a brand would have to [wait] to go into the design stage,” says Sasha Calder, vice president of impact at Genomatica.

For example, by 2012, Genomatica had made more than five million pounds of a widely used chemical generally referred to as BDO, found in a huge range of fabrics and plastics. But instead of manufacturing BDO from fossil fuels, Genomatica used computer modeling and genetic engineering to create E. coli bacteria that would process sugar and turn it into BDO. It’s the same chemical, just from a far more renewable source.

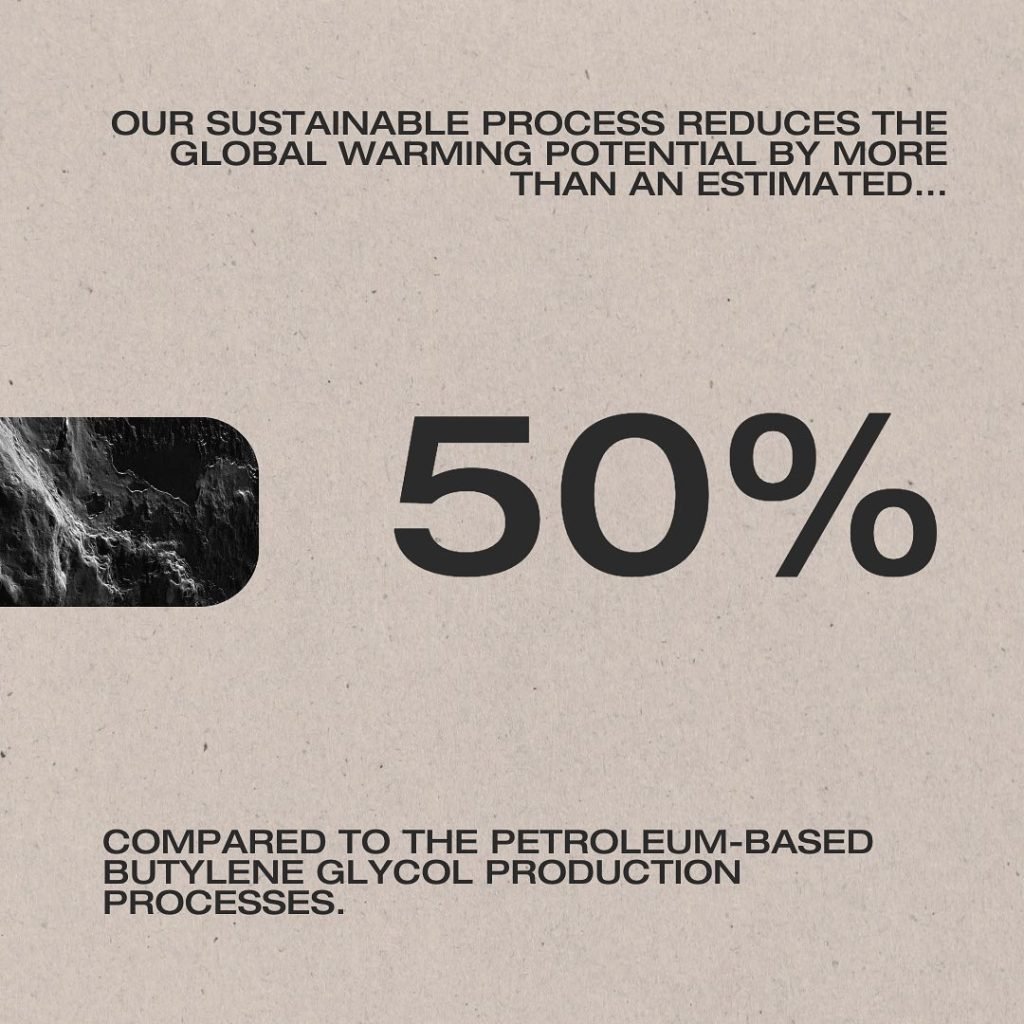

Genomatica also created a beauty ingredient called Brontide, used in shampoos, conditioners, and high-end lotions. Brontide is made of butylene glycol, a chemical usually derived from petroleum. Genomatica’s plant-based butylene glycol can be utilized in exactly the same ways: to create the right texture in moisturizers and to boost antimicrobial properties. It drew the attention of Dermalogica, a subsidary of global behemoth Unilever, who switched to using Brontide and created a campaign to raise awareness of the change among their customers.

Investments from major brands have helped fund the company’s research. In 2021, Lululemon signed on to help Genomatica develop a plant-based nylon, and, on Earth Day this year, they launched their first products made with the material.

Genomatica is also working with companies like Unilever and L’Oreal on replacing palm oil in their merchandise. While palm oil is a plant-based ingredient, growing it is ecologically devastating, with massive swaths of tropical forest in Asia, Africa, and Latin America being cleared to make way for oil palm cultivation. As an alternative, Genomatica is creating a new line of products called Future Origins, which will help companies address consumer demand for avoiding palm oils and meet new regulatory requirements, like the EU’s ban on products linked to deforestation.

Calder says there isn’t much financial data on the company that she can share publicly, but she reports that, in 2021, Genomatica brought in $48 million in revenue and is continuing to grow. Their plan is to partner with more companies and develop new materials with increasingly resilient supply chains.

PARTNER CONTENT

For Calder, and many other employees, their work at Genomatica allows them to create change at the root of the push for sustainability, rather than working within manufacturing companies and trying to convince them to change their ingredients.

“I can go into my bathroom and use products that I know come from plants instead of an oil rig, and I feel really good about it,” Calder says.