“I think of us as a culture of deniers,” John Halaka says. “We tend to shy away from complex topics. We tend to shy away from our responsibilities to the histories that brought us to where we are.”

The artist, a professor of visual arts at the University of San Diego, has spent much of his life immersed in those histories. Moved by the US Civil Rights Movement as a college student, Halaka developed “a deep-seated interest in justice and in human rights,” he says. He studied the history and politics of Palestine, eventually traveling there to interview and record individuals’ memories and stories. As a Fulbright scholar in 2011 and 2012, he spent nearly a year in Lebanon working with four generations of Palestinian refugees, an experience that deeply informed the pieces in his new exhibition at the Oceanside Museum of Art (OMA).

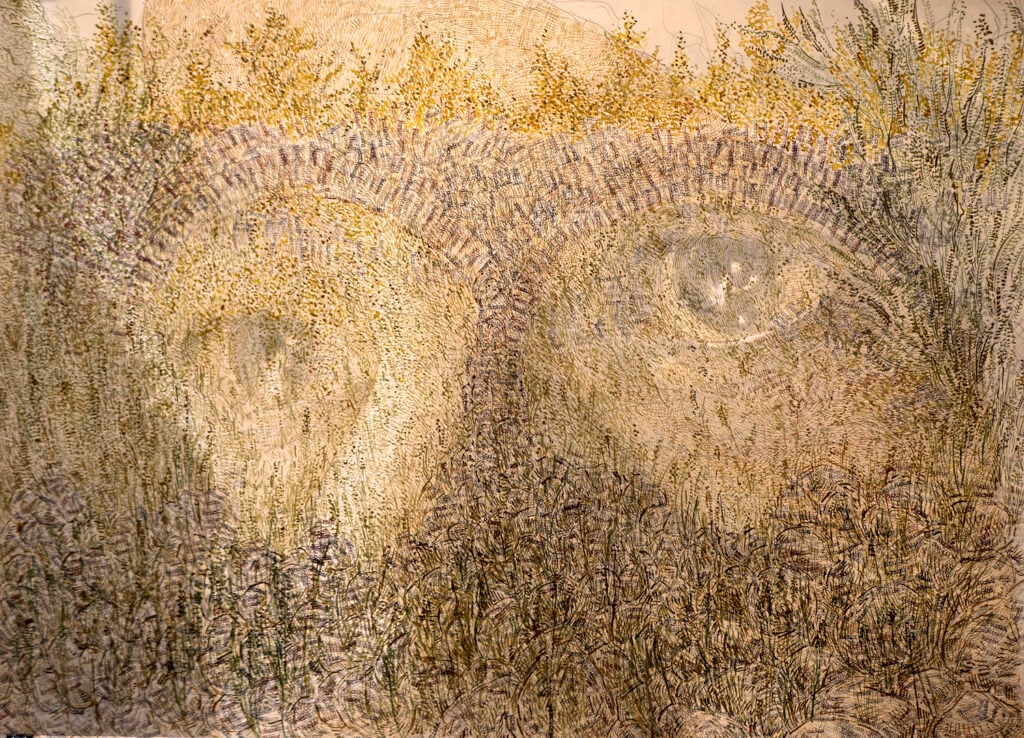

Entitled Listening to the Unheard/Drawing the Unseen: Meditations on Presence and Absence in Native Lands, the exhibition runs through February 18. Hung in stairwells and filling two galleries on OMA’s second floor, Halaka’s drawings—portraits of the people he interviewed, interpretations of the narratives they shared—are enormous, arresting, beautiful. And their meaning is undeniable.

It’d be easy to imagine the exhibition’s titular absence as emptiness, faint outlines, blank space. But Halaka’s work is the opposite. His drawings are densely layered, packed with stamped words (“RESIST” and “REMEMBER” among them) and tiny lines that coalesce into faces, hands, thorny vines. Approach too close, and they dissolve into visual snow.

“Absence and presence are essentially the two sides of a coin,” Halaka says. “When I engage with displaced individuals, there’s always this duality. They’re absent from the land, their homes; their history has been shattered. But all of that history is present within them. I try to visualize that by having two or more things exist at the same time.”

Some of Halaka’s most moving works superimpose portraits of Palestinian refugees over photographs of villages that were destroyed in Palestine in 1948—or vice versa, with the villages drawn over photos of the refugees. Faces, bodies, and buildings are rendered semi-transparent, ghostly. When underlaid beneath the portraits, the ruins appear as part of the refugees, giving texture to their skin.

A few pieces in the exhibition feature drawings of activists (including Lakota author Mary Brave Bird and Palestinian historian Hussein Lubani) on maps of the US and Palestine, visually melding people and their ancestral lands.

Other works, less layered but no less complex, are portraits and drawings made with a wood-burning tool. Thousands of scars form images on large panels of reddish oak, referencing “the cuts and burns that shaped [the refugees’] lives on a personal, communal, and national level,” Halaka explains.

I ask Halaka how he approaches the responsibility of translating others’ experiences for a wider audience. It’s a question that plagues me as a journalist, I admit to him.

He says that, in some ways, their story is his story—as the son of a Palestinian father and as an immigrant who came to the United States when he was 12, he shares many cultural touchpoints with the people whom he interviews, though he himself was not a refugee.

PARTNER CONTENT

But even more critically, “I’m very, very aware of asking permission and of letting them guide my learning process,” he says. Behind each piece on the museum’s walls are hours of trust-and relationship-building with the refugees whose narratives he transforms into art. “I’m allowing their stories to shape me,” he adds. “I’m the empty cup waiting to receive knowledge so I can grow from that knowledge.”

Halaka hopes that, for museum visitors, viewing his art is merely the beginning of their own process of confronting the legacy of settler colonialism. “My drawings don’t tell the whole story,” he says. “They’re little stanzas of a much longer story.”