humpback-whale-sdm1222.jpeg

Photo Credit: Domenic Biagini and Gone Whale Watching

I admire the ocean, but question its motives. It’s tried to kill me too many times—face down, throat full of sand. The ocean doesn’t give a f***1 about us. Sure, it sings to many in a low ancestral whisper, but I promise that’s only to draw us in. In reality, it’s a sneaker-wave, riptide deathtrap, trying to kill all who come near, to drag them to suffocating depths and turn their flesh into a clambake for countless nightmare creatures that swim, slither, and crawl invisibly below the surface. Ever seen a Goblin Shark? The ocean is terrifying.

Yet it’s home to creatures I have long craved proximity to and knowledge about: Whales.

So, Dramamined and sunscreened, I rode a swift boat on an early October morning with five strangers and our captain out of Mission Bay to go whale watching. We were instructed to meet behind a seafood market, where stiff coffee-table-sized yellowfin tuna lay piled in wagons, dripping watery puddles of blood. From our captain, we were each given a form to sign that said if we died a sailor’s death out on the open sea, it would be no one’s fault. Our captain and his employer could not be sued. The ocean, after all, is extremely f******2 dangerous. Of course we’re all going to die out there, I thought. Everyone signed.

Puttering 5mph through the no-wake zone, I was thinking about the magazine this story would be appearing in, San Diego Magazine’s annual issue dedicated to the environment. As a reporter, I’m fascinated by human consciousness and how media both propels and inhibits it. As an editor, I’m curious how a legacy regional magazine like this one can best serve to complicate our reader’s thinking on issues of ecology. How can a magazine that operates in a capitalist system approach ideas around so-called sustainability without reducing them to feel-good platitudes? By being honest, I think.

Big And Old And Sort Of Back In Business

Dinosaurs are generally thought to have been these massive lumbering behemoths, but, the truth is, whales are bigger. A blue whale—which one could theoretically go out and see today, depending on one’s location and luck—can be as big as thirty T-Rex. Thirty. They are the largest creatures to ever exist. Jurassic Park is a flea circus.

Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) were once hairy land mammals that slowly made their way into the water for food before evolving into the sleek swimmers we know them to be. A few species even retain whiskers from this evolutionary journey. Whale goatees.

These hipster whales we know today began evolving around 50 million years ago, meaning whales were dominating the oceans—forming culture, customs, and language—long, long before humans existed. Whales swam in these very oceans as paleolithic pre-humans grunted and froze in caves, as Jesus walked dusty-footed through the desert, and they swim here now, with baleen species eating a couple tons of fish and krill per whale per day, then releasing long greasy clouds of excrement that feed the phytoplankton that then feeds the krill in a timeless cycle that humans nearly eradicated in a matter of decades through commercial whaling.3

Blue Whale SDM.jpg

Photo Credit: Domenic Biagini and Gone Whale Watching

Today’s whales are largely protected if you don’t count pollution, ship strikes, and suicide-inducing underwater noise from commerce and the military. But for a couple of centuries, humans efficiently slaughtered them like sardines. Humpback populations were believed to drop from tens of thousands to mere hundreds worldwide.

It wasn’t until multiple species were all but extinct that commercial whaling was banned, finally, in 1986. The end of international large-scale whaling proved that given the chance, nature rebounds, which we saw again, briefly, with the global economic Covid slowdown in 2020. Humpback populations are now thought to be above 90 percent of what they were before commercial whaling, for example. A rare conservationist success story of sorts.4 But the oceans, generally speaking, are not in good shape. Eleven million tons of trash enter the oceans each year.5 Each week, it seems, we see entire neighborhood’s worth of natural disaster detritus washing away from tsunamis and hurricanes. Cars full of petrochemicals, entire buildings. Where does all that go? Not to a recycling plant. Sure, the ocean would love to kill each of us, but we are much more efficient at killing it with our simple daily routines and the cheap plastic systems that support it. Something has to give.

The ocean is home to an incredibly ancient and complex latticework of ecosystems comprising 80 percent of all life on this planet. But rampant carbon emissions from people mean a warmer and more acidic ocean, which severely stresses the intricate tangle of life below.6 It’s dire, but ironically the situation isn’t all negative. Warmer waters can actually help some whales thrive.

At The Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Simone Baumann-Pickering listens to whales for a living.7 As a professor of biological oceanography, she uses underwater recorders to study how man-made noise, like military sonar, impacts whale behavior.8 She sees whale behaviors changing due to the climate crisis.

“It’s really geographically distinct whether animals are doing well or not,” she told me. “You have to look at the individual stock level. Some are benefitting from changes, and some are not. Arctic whale habitat is shrinking due to ice loss, but tropical species might be able to expand their range.”

“You see baleen whales growing in numbers, but that’s not true for every species and population,” she added. “Generally speaking, the rebound isn’t as fast as we would hope.”

Millionaire Cetaceans

Whales have captivated me since childhood, but my ardor grew more, um, ardent, while living in Baja, as close to the ocean as one can get. Waves like a thunderstorm waking me in the night. In the winter, Humpbacks and Greys migrate up the Gulf of California to calve. They then migrate, baby in tow, back to the Pacific and north for the summer, where the waters are cold.

Along the way, the adults teach the calves songs and customs, whale traditions and know-how that go back before the dawn of man. The mothers teach them how to jump, how to communicate. Binoculars in hand, I would watch for hours from a hammock on my deck.9 Ever more infatuated.

breaching-humpback-dec2022.jpeg

Photo Credit: Domenic Biagini and Gone Whale Watching

In her 2022 book, The Value of a Whale: On the Illusions of Green Capitalism, author Adrienne Buller writes about the IMF placing a whale’s monetary value at around $2 million USD. Capitalism, of course, has a way of reducing everything to market-compliant units, even something as invaluable to the spirit and imagination as whales. As someone choosing whales as a focal point, I asked her why she had done the same.

“They’re a species that has, for generations, been under severe threat through processes intimately related to the development of industrial capitalism,” she responded. “From the profound devastation of global whale populations under commercial whaling to the accumulation of PCBs and contemporary pollutants in their blubber creating a ledger of our impact on the oceans, whales have an acutely visible relationship with the development of capitalism and its planetary impacts.”

Whales tell us about ourselves. 200-ton, eight-figure storytellers.

Three Balloons, One Whale

Late fall is hit or miss for San Diego whale watching, but the dolphins alone are worth the price of admission. Numerous dolphin species can be found off the coast of San Diego year round. On the boat, we were surrounded by the hundreds. Polished bodies swimming beneath and alongside the boat, baguette-length baby dolphins everywhere.

In our two-plus hours, we encountered one whale—a Bryde’s (pronounced broo-dees)10—plus a mylar balloon reading Get Well Soon and two other semi-deflated balloons floating some five miles offshore. Our boat driver, Tai, a handsome, mustachioed OB guy, slowed to pick each out of the water, knifed them, and shoved them in a built-in cooler. “Good ocean karma,” he called it. “We pick up like ten per day out here.”

As an ocean lover, I experience visceral pain hearing such things. Balloons in water are dangerous. Their color eventually bleaches so they resemble jellyfish.

get-well-soon-SDM.jpg

Creatures that eat jellyfish—like sea turtles and some whales—gobble them up, and since the balloons don’t digest, the creatures stop eating and die. Some 50 million balloons are sold in California alone each year. Polyurethane balloons take hundreds of years to decompose. Mylar ones never do. Get Well Soon is full of irony. It will outlast humanity, much less the person it was gifted to.11

Our actions have consequences, we all know this. But will readers fill fewer balloons? Be more careful not to let them go outside? Maybe. Or maybe not. That’s not the point.

In putting together this environmentally-focused issue of SDM, we didn’t want to sell our readers the idea that we can buy our way out of the climate crisis, a trope that’s all too common in the media and especially in advertising.

Buller said it well: “One of the central tasks of ‘green capitalism,’” she told me, “is to devise and offer ‘solutions’ to the escalating climate and ecological crisis that minimize any disruption to the way we currently organize our economies and societies.”

She continued, “A big part of this involves selling the idea that all these crises require are market fixes and technical innovations—a politically sellable idea that has little basis in scientific reality or, for that matter, questions of justice and/or building a better world.”

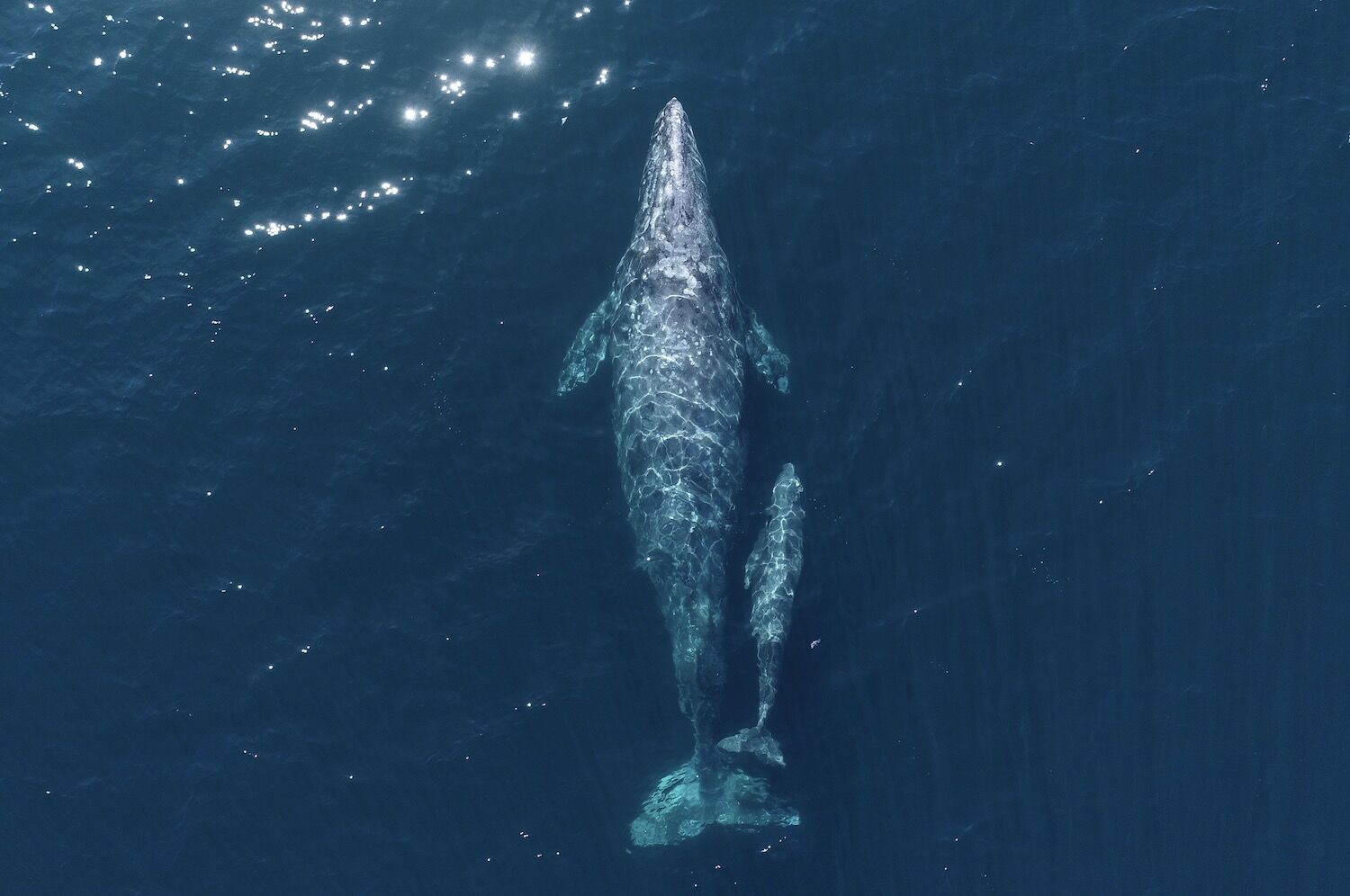

gray-whale-sdm1222.jpeg

Photo Credit: Domenic Biagini and Gone Whale Watching

The way we spend our dollars matters, make no mistake. Planet-forward ideas and products deserve to be celebrated, but they only go so far. The truth is we’re not going to recycle our way out of climate catastrophe. Truly meaningful solutions can’t be purchased online. Our hyper-consumptive way of life, the racist systems that prop it up, and the industries that profit from it are the problem.12 Capitalism painted green won’t solve the problems bare capitalism creates.

New Old Friends

Back on the boat we watched the Bryde’s whale swim slowly towards a ball of fish the dolphins had corralled, various sea birds strafing above. Bryde’s are a tropical species of baleen whale that may be coming north more as waters warm. It’s fairly rare to see around here, but not as rare as, say, a beaked whale, which one might also be lucky enough to see out here. The waters off San Diego are fertile with life. Of the 75 or so whale species, nearly one-third are beaked whales that have evolved to forage deep sea squid at skull-crushing depths. They can stay down for hours.

“Beaked whales are elusive,” Bauman-Pickering said. “They only surface shortly and stay down a long time.” The best way to study them is by using multiple acoustic sensors, like she does.

“In the beaked whale world, we have discovered four or five new species in the past 20 years,” she said. “One as recent as five years ago.”

WHAT.

I fully interrupted. Legit yelled through the phone. The fact that humans are still discovering new whales floored me. Despite all the problems it faces, the ocean remains full of big surprises. I love it. The ocean kills me.

gray-whale-tail-sdm1222.jpeg

Photo Credit: Domenic Biagini and Gone Whale Watching

- [1] fish

- [2] fucking

- [3] Phytoplankton create more than half of the Earth’s oxygen, meaning whale poop is fundamentally important to life both on land and at sea.

- [4] At least for now.

- [5] According to the UN. Almost 90 percent of plastic found on the ocean floor are single-use items like plastic bags. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is comprised of nearly 2 trillion pieces of floating plastic. It’s three times bigger than France.

- [6] According the UN, “Ocean acidity has increased about 26% since preindustrial times. At this rate, an increase of 100 to 150% is predicted by the end of the century, with serious consequences for marine life.”

- [7] A job I am acutely jealous of.

- [8] She has “no shame” about eavesdropping on them.

- [9] I was an unpaid caretaker of this property, for what it’s worth.

- [10] Until writing this I thought it was pronounced brides. The whale gets its name from a Norwegian guy who set up a whaling operation in South Africa around the turn of the 20th century. Naming a whale in this manner sounds to me like when a city is named after the first person to facilitate genocide in the area. Bleak, offensive, and uninspired.

- [11] It’s worth noting that the helium Tai poked out is a finite resource that’s running low. Helium is used in life-saving medical equipment like MRI machines. But once it’s gone it’s gone. Fewer people will be getting well soon.

- [12] From Buller’s book I learned about a footnote in a briefing on inflation in which an economist at the federal reserve wrote, “that for the purposes of his briefing he would regrettably ‘leave aside the deeper concern that the primary role of mainstream economics in our society is to provide an apologetics for a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.’” Well put.