If architecture is music frozen in time, this house sings.

Rising from a steep La Jolla canyonside, three bold orange steel beams prop up a midcentury home like the saddle of a guitar cradling the strings. But here in the sky, the chords are muted. It’s quiet. Hawks circle just outside, enjoying the same views of Bird Rock Beach and the short-tempered Pacific as the people lounging within. At this height, with a wall of west-facing glass, the main living area feels as though it’s dissolving into the exterior.

“Nature is right there,” says owner Joan Gand, standing near the home’s impressive living room fireplace. “This is a big tree house; the lines are blurred between inside and out. One of the really magical experiences is when the fog rolls in from the ocean and you feel like you’re living in a cloud.”

“All of a sudden, you’re floating,” adds Joan’s husband of nearly 50 years, Gary. It’s like something out of a science-fiction movie.”

If one looks at pictures alone, it’s easy to assume that being in this house feels like wobbling on a pair of stilts. Precarious. But even though the original main floor—with living room, kitchen, master suite, office, den, two bathrooms, and a wrap-around deck that serves as an outdoor hallway—stands on its tippy toes some 40 feet from the shrubs below, the residence feels solid, grounding even. This is despite the fact that, when the house was built in 1961, barely any of the structure touched the earth.

“It’s kind of like a martini glass,” Gary says. “The real engineering feat of the house is that there’s a minimal amount of attachment to the land. The majority of the weight of the house is on the T-beams. It’s quite the balancing act.”

“Yet, at the same time, you feel anchored,” Joan adds. “It’s solid. The structural engineer told us, ‘When the big one comes, you’ll be standing here watching other houses fall into the canyon.’”

Safe to say, they simply don’t build them like this anymore.

“It’s an acrobatic way to suspend a home—all the drama is underneath,” says local modern architect Sean Canning, who I asked to accompany me on my first visit to the home to help me better understand the singularity of what we were seeing. “This kind of craftsmanship and vision just doesn’t happen now. The permitting process today would make this house almost impossible to build.”

Yes, times have changed, and so have regulations—which is part of why original midcentury architecture remains so beloved. The home is a product of an era when building permits practically came in cereal boxes, and if no one showed up to stop you from doing something on your property, you were essentially free to do it. It was in this spirit that engineer-turned-builder Robert Liebner designed and constructed the home with his wife Becky after scoring the lot on which it stands for a song.

“It was a very cheap lot. Pretty much considered unbuildable,” says the couple’s younger daughter, Renee Savigliano, 70. She and her sister Ginny Liebner Jones, 72, grew up in the home along with two younger siblings. “But my father had the confidence to make it work.”

Making it work included craning in the international orange T-beams, then bolting them to large concrete pyramids, the bases of which were buried in the ground.

“My dad liked a challenge,” Jones says. “When the house was being built, everyone assumed there was a bridge going across the canyon. It was an incredible feat of engineering.”

Liebner’s home is a testament to DIY-ism and creative problem-solving. And after decades of quietly humming along, its song is playing again in full volume. A midcentury melody composed in steel and glass, remastered to its heyday splendor.

Thanks to the Gands, this form-meets-function flex of engineering is getting a second wind. What was an aging house with piecemeal renovations has been transformed into a modernist time capsule, refreshed with period-specific antique finds and six figures in restorations, the bulk of which were done personally by master craftsman John Vugrin, whose iconic work on the Kellogg Doolittle house in Joshua Tree is the stuff of legend.

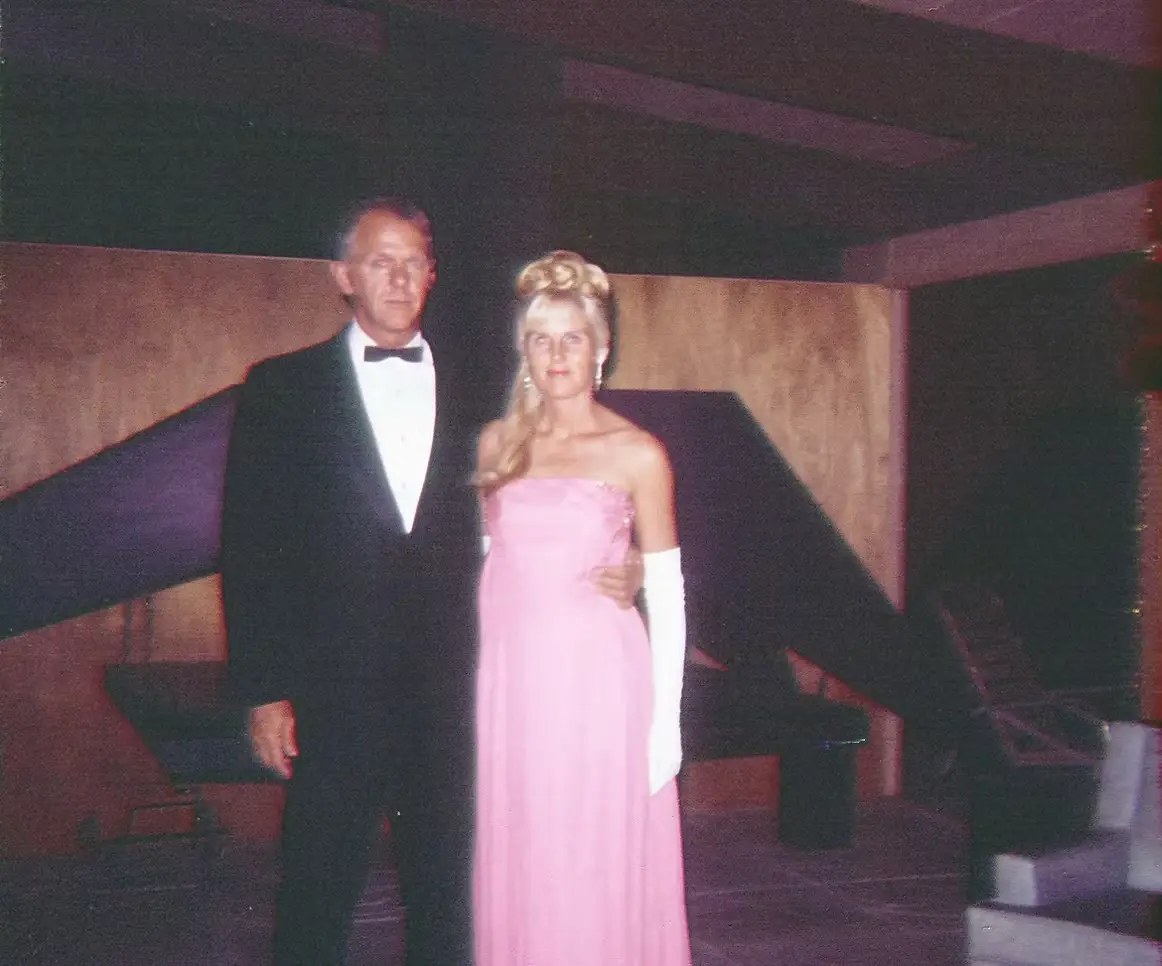

When the Gands sold their Chicago-area retail music store in 2016 to remotely run their commercial sound business, they were able to dedicate more time to becoming preservationists and gig musicians (they play in a Palm Springs–based band together). In 2019, they discovered the home and knew they had found something special. The couple have under their belts nearly a dozen multimillion-dollar midcentury restorations, but this one, they both say, is different.

“It’s our favorite,” Joan says.

“It is,” Gary echoes. “We spent the most time on it, and we had the best restorer.”

“The combination of geometry and the warmth of the wood and the fact that nature is all around us—that’s what really makes it sing,” Joan adds.

As we tour the home, Canning points out distinctly midcentury details, like the way the roof sits directly on top of glass in the living room. “When the designer and the structural engineer are one and the same, you end up with something super cool like this,” he says.

Not long after the home’s completion, when Savigliano and Jones were 7 and 9, Liebner and Becky divorced. Becky soon married Bill Ivans and the two purchased the house from Liebner months later. Becky and Ivans had two more children, and, needing more space for their family of six, they hired the best possible person to add an addition: Robert Liebner.

The bottom floor he designed partially rests on the hillside, with the lower ocean-facing deck dominated by the underside of the orange cantilevers. With walls of glass similar to those upstairs, the large downstairs living room is alive with light and proves multifunctional. An accordion door closes off to form another bedroom, leaving the downstairs bathroom accessible. A unique set of stairs joins the home’s two floors.

“My father built one of the first spiral staircases in San Diego, and it wasn’t a kit,” Jones says. “He designed it and built it himself. His original idea was for the railing to have ship-like ropes, but my mother wasn’t a fan.”

Becky, to her credit, was the primary decision-maker when it came to the home’s interior design.

“She stayed with the house through three marriages,” Joan says. “She’s the spirit of the house.”

Over the years, the Ivans’ place wasn’t merely a home—it was an experience, the open layout reflecting Becky and Bill’s open-door policy. The parties were epic, and the stories grew. At one point, a neighbor crashed a Rolls Royce into the front of the house, prompting reconfiguration of the garage and the front den area upstairs. Through it all, Becky remained a spitfire hostess, ready to welcome all.

“My mom’s idea of hospitality was spontaneous and inclusive,” Savigliano remembers. “The house was a hub—we had random people there all the time, from teenagers crashing for the summer to international visitors who stayed for years. And my mother would bring kids from Tijuana who needed medical treatment to live with us for various periods of time.”

“We had Christmas parties for 400 people,” Jones says. “It was elbow-to-elbow. You could walk around the outside deck faster than you could get through the house because it was so packed. And it was an incredible place to grow up— the open-concept design meant we could host 70 kids for youth group meetings, and it never felt crowded. It was the ultimate party house.”

After Becky died, her children decided it would be best to let someone else enjoy the residence. In the Gands, they found buyers who didn’t only value the lot— they valued the home as a piece of history.

“We wrote a letter promising to restore the house,” Joan recalls. “Everyone else would have torn it down. That’s why they chose us.”

“The Gands bought the house because they love architecture,” Jones says. “We had other offers, but we wanted someone who wouldn’t tear it down or change it too much. It’s a house that deserves to be preserved.”

These days, large parties are not unheard of, and the staircase railing includes rope, both thanks to the Gands. They also knocked out an entryway closet, replacing it with era-specific bas-relief paneling from famed midcentury California artist Evelyn Ackerman; landscaped the canyon below; completed a full refresh of the exterior redwood siding; added walnut parquet flooring upstairs to match the original lower level floor; overhauled the master bath; and fully remodeled the kitchen.

“We redesigned the kitchen based on old snapshots of the original layout,” Joan says.

The kitchen, while modest, feels expansive, preserving the open feel of the house and positioning the range so that the cook gets an ocean view.

The couple’s work on the home earned them a People in Preservation Award from the Save Our Heritage Organization, a La Jolla Jewel Award, and a Historical Landmark designation. But despite all the top-notch renovations and accolades, it’s the original Liebner-designed fireplace that steals the show. Still futuristic-looking and fully operational more than 60 years after it was first constructed, the gas hearth anchors the energy of the home today, as it has for decades.

“I love to be on the sofa in the living room looking at the fireplace and the views outside,” Joan says. “It’s like a piece of sculpture. It’s also kind of Space Age; it has the feel of flying.”

“Which, in a house suspended in the air, is apropos,” Gary adds.

Today, the house is alive again, its midcentury melody restored. The Gands open it to the public periodically as part of a La Jolla Modern Home Tour they help organize each fall with the La Jolla Historical Society.

PARTNER CONTENT

“The house is so special, and there’s so much to be seen, learned, and enjoyed from places like this,” Joan says. “We feel like architects coming here and touring the house could influence design in a good way, because, let’s face it, modern design isn’t what it used to be.”

Which is why the Gands do what they do, educating people about the importance of modern design and preserving homes like this, one at a time. Because, now given the chance, this house, with its floating foundation and its seamless connection with nature, is more than an extraordinary performance—it’s a song playing on.