There’s a reason why, of the nearly 100 neighborhoods across the country Marco Li Mandri and his company New City America have helped transform, Little Italy is closest to Li Mandri’s heart. He was born there in 1954.

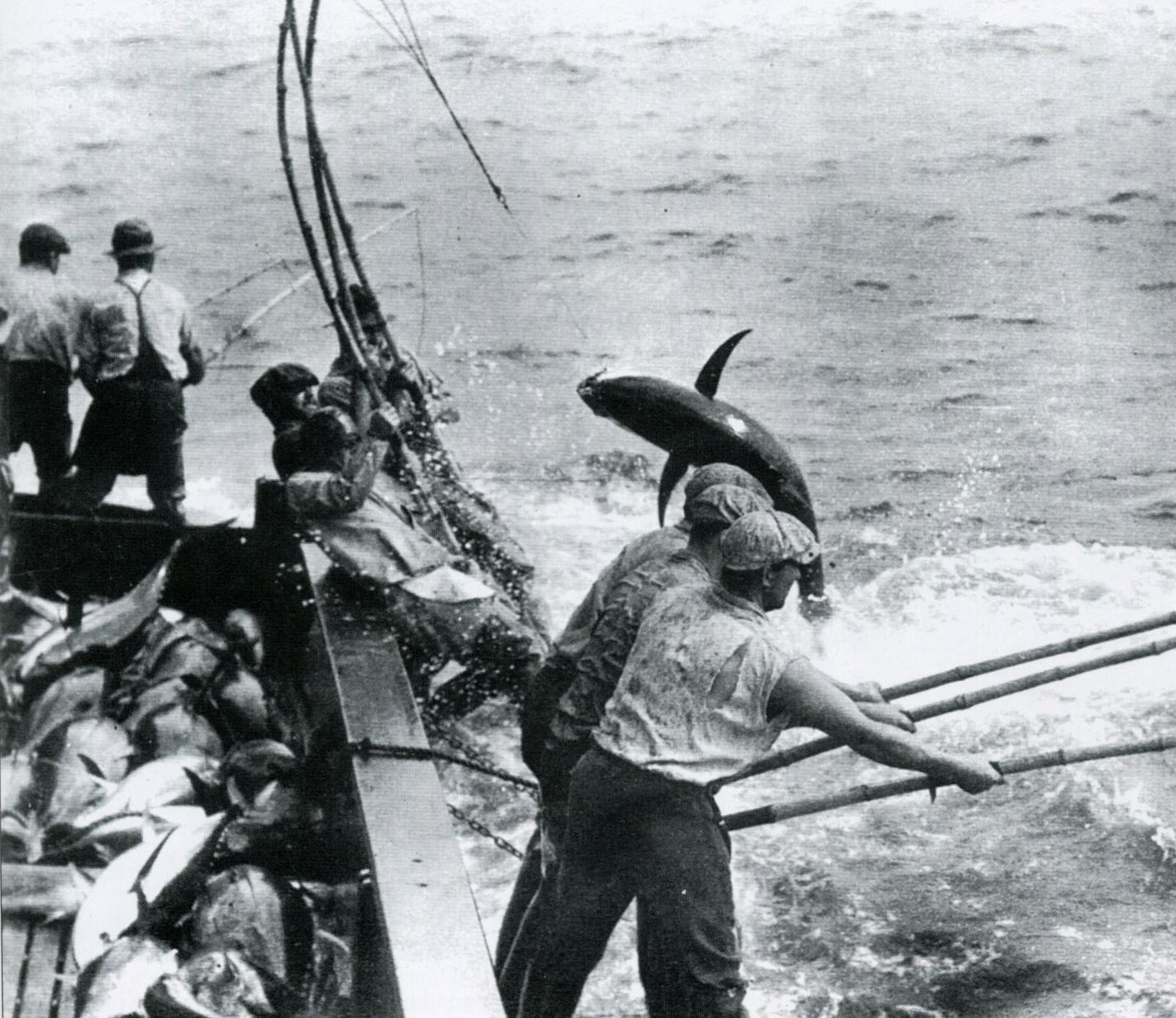

In those days, Little Italy was still a stronghold for the canneries that helped make San Diego the tuna capital of the USA in the 20th century. Immigrant fishermen from Italy and Portugal sourced product from the Pacific for the canneries, which employed thousands of people. But the I-5 tore through Little Italy in the 1970s, replacing huge swaths of homes, and rising costs and competition forced the last canneries to shutter a few years later.

“The worst thing for all of us [was] when the freeway went in,” beloved Little Italy resident Rose Cresci told San Diego Magazine in 2001. “It devastated this neighborhood.”Many residents ran for the hills (that is, the suburbs). Little Italy lost its distinctive character.

By the mid-1990s, the neighborhood was “mostly parking lots,” Li Mandri says.“There were no stop signs on India Street. Kettner was all industrial.”

A former food manufacturer, Li Mandri had pivoted to development consulting, helping boroughs like West Hollywood create what are called Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), organizations formed by property owners in the area. Local businesses pay fees to the BID, which uses that money—as well as cash from events, fundraisers, and sometimes grants or taxes—to fund services in the neighborhood beyond those provided by the city, from basic sanitation needs to large-scale development of public spaces.

The result, in many cases, is an influx of hustle, bustle, and—critically—capital to once-sleepy areas. San Diego tourists don’t add Little Italy to their must-visit list for the area’s industry history, after all. Today, they come to eat in its restaurants, poke through its shops, and sip Aperol spritzes in its town squares.

But all of that activity began a few decades ago with a sign. “I started getting really involved in Little Italy, and I said, ‘Everybody’s got one of these signs,’” Li Mandri recalls, referring to the now-iconic lit crests that bear many neighborhoods’ names in San Diego. “What they really represented was the town center. [I knew] we could use community development grant money to [get one].”

He and a group of Little Italy business owners formed the area’s BID in late 1996. By 2000, they’d secured enough funds to put up their sign. They redid the neighborhood’s water lines, replaced its century-old sewer pipes, and designed and installed its first piazza. “Then everything just went nuts,” Li Mandri says. “We had 2,000 condos built [in Little Italy] between 2002 and 2008.”

Currently, there are six piazzas in the neighborhood. The BID—the Little Italy Association—is responsible for managing trash collection, greenery maintenance, and events like the weekly farmers market, Taste of Little Italy, and the annual Festa. At 48 blocks, the neighborhood is the largest Italian-American cultural district in the country.

Little Italy’s Business Improvement District, the Little Italy Association, helped make major structural changes to the neighborhood.

New City America has since made its mark in areas as disparate as downtown Glendale, CA; Nashville’s Upper Broadway; and Washington’s Bainbridge Island. Now the company is working on replicating its success in Little Italy in two other San Diego neighborhoods: East Village and Chula Vista.

“[What we do] is for the public good,” says Dr. Gonzalo Quintero, owner of Chula Vista’s Vogue Tavern and president of the Downtown Chula Vista Association, the area’s BID. “But we’ve also seen that we’re very capable of producing events that … are actually money-makers for the organization. The more money we have, the greater ability we have to take care of things [like] landscaping and architecture.”

But the approach has its critics. In 2012, four years after New City America helped establish two BIDs in downtown and uptown Oakland, writers Adrian Drummond-Cole and Darwin Bond-Graham argued in environmental and social justice journal Race, Poverty and the Environment that “BIDs greatly increase the political power of those who own land and buildings at the expense of the non-property owning majority … The entire process hinges on an intensive gentrification effort in which undesirable categories of persons and activities associated with them are removed.”

Quintero believes that Chula Vista’s BID will benefit the community as a whole. “A rising tide literally does raise all ships,” he says. “For private property owners—business and residential—in the area, the property value is going through the roof. Now, that obviously will affect renters, but for those that have lived in the community, they’re starting to see a huge leap in their personal equity.”

And, housing security, Li Mandri insists, is intended to be part of the plan—including for renters.“ We’ve been a strong advocate of affordable housing in Little Italy,”he says. He points to Kettner Crossing, a 57-unit, eight-story community for low-income seniors, currently under construction at the intersection of Kettner Boulevard and Cedar Street on an $11 million lot donated by the county. “We always say that the most successful [communities] are mixed-use, mixed-income, mixed-race, and mixed-age,” he adds.

A number of longtime residences owned by old Little Italy families remain on India Street, framed by restaurants and boutiques. “If they want to sell, that’s up to them,” Li Mandri says. “But we’ve always told people you could not eminent domain somebody that was living in a [home] where they were born and raised.”

He asserts that New City America’s goal is to preserve and highlight the cultural history of each area they enter. In Little Italy, that meant banners celebrating change-making Italians and events like Festa that honor Italian-American customs.

In Chula Vista, the association nods to the city’s history as the one-time lemon capital of the world with the Lemon Festival. In December 2023, Chula Vista’s traditional holiday Starlight Parade returned after a three-year hiatus. “The police estimated there were 60,000 people at the Starlight Parade,” Li Mandri says. “So we know that there’s all this pent-up demand—whether it be from families that come across the border from Tijuana or all throughout the South Bay—for a town center.”

The Downtown Chula Vista Association’s plan for the city includes expanding public gathering space in Memorial Park.

The Downtown Chula Vista Association is also aiming to expand public transportation in the city and build more dense housing. The Gaylord Pacific Resort & Convention Center, planned to open on the bay in 2025, has promised to offer a shuttle that will cart guests to Third Avenue to explore downtown Chula Vista’s restaurants and shops. The association is partnering with the mayor and the city council to create a public gathering space in Memorial Park, the area’s version of Little Italy’s piazzas.

PARTNER CONTENT

Quintero envisions Chula Vista as a “15-minute” city, where all of residents’ daily needs are accessible within a short walk.

“That’s the next phase of Third Avenue in downtown Chula Vista,” Li Mandri adds. “[Becoming a place] where people are able to live [in] affordable and market-rate housing. They’ll be able to walk down the street and go to work and send their kids to school.”