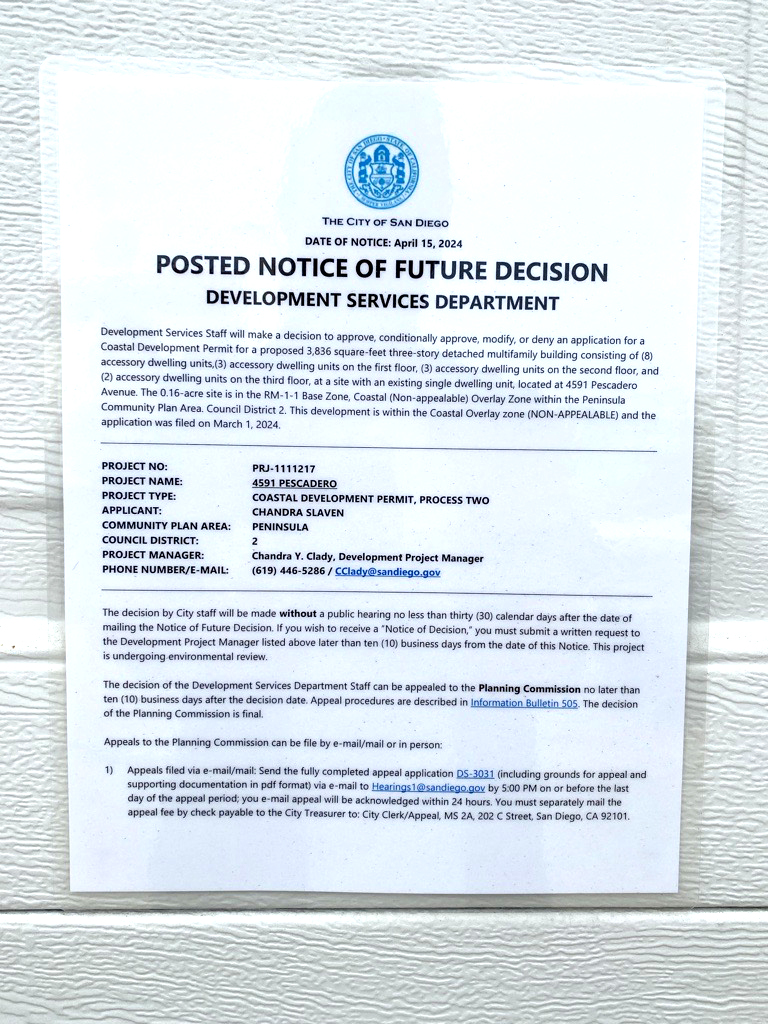

Recently, Jerry Ruiz received a notice that a three-story, eight-unit Accessory Dwelling Unit—also called an ADU or granny flat—is going up near the corner of Froude Street and Pescadero Avenue, across the street from Ruiz’s house in Ocean Beach, where he and his family have lived for more than 10 years.

“We are pretty upset,” Ruiz says. “It’s just going to make OB more of this vacation, tourist spot, when OB always had more local flavor.”

Ruiz chose to live in Ocean Beach because it felt more family-friendly than other coastal neighborhoods, like Mission Beach. But he’s concerned that the ADU will be “inconsistent with what was zoned as a family, residential neighborhood.”

In 2020, the city passed the Complete Communities program, allowing developers to increase density near public transit in exchange for including subsidized units in their buildings. The city also passed the ADU Bonus Program, which allows owners to build an extra unit for each one reserved for renters earning below a certain income.

These initiatives have yielded some results, though they’ve had less impact than policies in other cities that did away with single-family home zoning, opening the door to multi-unit buildings on lots that once held standalone houses. Last year, San Diego issued a record number of housing permits—9,691—though that amount still falls far short of the city’s annual need of roughly 13,500 units, according to The San Diego Union-Tribune. Permits for ADUs almost tripled last year, making up nearly 20 percent of the total number of housing permits.

Roughly 40 ADUs have been permitted near current and planned transit in Ocean Beach since 2020 (out of the 4,900 permits issued citywide during that same period). But the reforms have shifted the definition of “ADU”—many of these are multi-unit structures, effectively bringing apartment buildings to people’s backyards.

The tension surrounding these units is not unique to OB. ADUs are going up throughout the city, and lower-income and more diverse communities like Encanto, Skyline, and Paradise Hills have seen far higher numbers of ADU permits since 2020 than OB. But that doesn’t mean the coastal neighborhood is embracing these new, larger backyard units. In fact, their arrival appears to be stoking long-standing fears that OB could lose its identity.

Ocean Beach Planning Board Chair Andrea Schlageter

In 2022, Andrea Schlageter became the Ocean Beach Planning Board’s youngest-ever chair. She’s found herself at the center of a battle for OB’s future as these city initiatives to create more housing challenge groups striving to maintain the neighborhood’s hippie, bungalow-by-the-sea feel.

“They fancy themselves technocrats at the city, and there’s nothing wrong with looking at data and looking at what other cities have done to spur development, but you need to then take that idea; meet with stakeholders, including community members; and adapt it to your situation,” Schlageter says. “No two cities are exactly similar, right?”

Schlageter fears OB’s smaller cottages could “all be wiped out and replaced with big, modern box buildings.” That would be a shame, she says, “because that is the charm of OB living—in your tiny-ass one-bedroom cottage by the sea, hanging in a little courtyard with all your other neighbors.”

Many also fear that increasing density without requiring developers to provide parking will lead to traffic issues, given the limited public transit that exists in OB. Only two bus routes currently offer all-day service on weekdays. New and upgraded routes are included in a regional transit plan for 2035, but those projects aren’t yet funded, meaning better public transportation isn’t guaranteed in this timeline.

And because the new development is largely residential, some worry there won’t be enough commercial fronts for the residents who fill these apartments. One multi-unit housing project proposed for the corner of Point Loma Avenue and Ebers Street, for example, was once a Mexican restaurant and grocery store—though the building has been vacant for several years.

Neighbors of projects are unhappy that some of the new buildings have no setbacks or buffer zones. They also say that the subsidized units in these projects will not be truly affordable and fear the market-rate units will become short-term vacation rentals due to the lack of enforcement and loopholes within the city’s policies.

“This was a great stepping-stone neighborhood, but, now, with the short-term vacation rentals, with the development opportunities, when these mom-and-pop landlords pass on or want to retire and get out of that game, no one who wants to be a small-time landlord is going to be able to buy them out,” Schlageter says.

Henish Pulickal, CEO of The California Home Company—a general contractor for ADU projects around San Diego—says if developers agree to a 15-year deed, owners can charge 110 percent of the area median income in rent, which would make a one-bedroom apartment approximately $2,570 per month, at or near the current average for OB (shorter 10-year deeds mandate lower rents). He adds that developers can turn the main house on a property into a vacation rental, even if the city won’t allow them to do the same with ADU units.

These potential profits make the projects pencil out, encouraging developers to build more housing, he says. And although those rents may not be affordable to lower-income San Diegans, they’ll still help address the region’s housing underproduction and high costs.

“It’s the economics of supply and demand,” Pulickal says. “If I have 12 places that I can rent for $2,500, it’s better than one place for $7,000.”

Pulickal points out that OB’s ADU potential is limited compared to other neighborhoods because it mostly has smaller lots that can only fit one additional structure beyond the main house. It also has a 30-foot coastal building height limit.

Planning board member and developer Tyler Martin

Tyler Martin, a developer on the OB Planning Board, says he supports these projects in OB. “We know we need more housing,” Martin says. “There’s really only two things we can do: We can either sprawl into East County or we can accept density into existing neighborhoods. It’s more green to have multifamily housing near transit than it is to bulldoze East County.”

Martin says that Newport Avenue, OB’s main commercial strip, has too many empty storefronts for residents to worry about the loss of commercially zoned properties. He is concerned about short-term rentals but thinks the city should further limit the number of vacation rentals allowed and step up enforcement, rather than restricting housing construction.

“People who already live in this neighborhood are trying to prevent other people from living in that neighborhood,” Martin continues. “I don’t think it’s about history or the environment or about retail space or safety. I don’t think it’s about any of that nonsense. It’s about, ‘I don’t want anyone else living next to me.’”

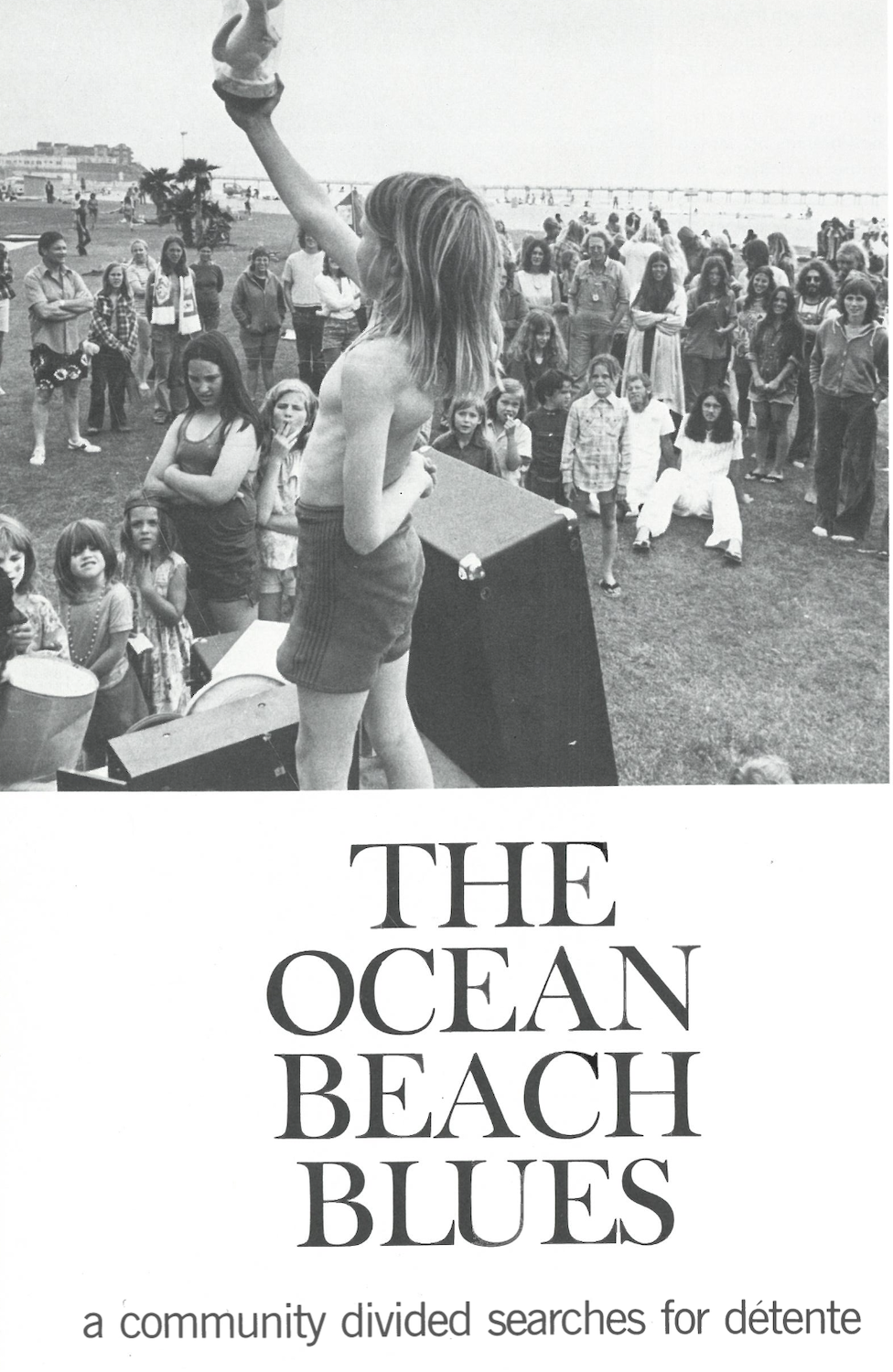

The battle isn’t new. The first community planning board in the city began in Ocean Beach in the 1970s in response to the 1960s Precise Plan. Endorsed by the City Planning Department, this plan aimed to increase density along the coast and intensify commercial activity on Newport Avenue, according to a San Diego Magazine article from 1974.

“It all devolves down to densities—how many should live in Ocean Beach and who they should be—what economic strata,” one city planner told SDM at the time.

Back then, the tension stemmed from fears of so-called radicals moving in and impacting the quiet livability of OB. Today, it comes from worries that backyard apartment buildings will impact OB’s quirky spirit. Density means change for those lucky enough to own homes in the neighborhood, but also it brings opportunity for those who hope to call it home.

In some ways the problem remains the same as they did in the ’70s, but the language has changed. Today, those opposed to development face criticism that they’re “NIMBYs,” meaning “Not In My Backyard.”

“I think it’s much more complicated than that,” Schlageter says. “Everyone wants their neighborhood to be nice … but it’s not going to be nicer if you just pray and spray development everywhere.”

PARTNER CONTENT

But Schlageter isn’t worried about OB becoming overly dense just yet.

“There’s still enough of the old guard walking around barefoot who will fight every project like hell,” she says. “I think we have a few more decades before we’ll see a mass sell-off of properties to developers in OB.”