Stop by The Loft on 5th Avenue on a Saturday afternoon, and you might find Andy Siekkinen in a cowboy hat and a red rodeo sash, carrying a platter of Jell-o shots. Don’t be fooled by his understated demeanor and quiet smile—Siekkinen is royalty. Gay rodeo royalty, that is.

This year, Siekkinen was the first runner-up for Mr. International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA). In the past two years, he won the distinctions Mr. Golden State Gay Rodeo (GSGRA) and Mr. Palm Springs Hot Rodeo. Despite all these titles, he’s relatively new to the world of rodeo.

Siekkinen grew up on a dairy farm in Ohio, but he had never ridden a horse until three years ago, when he learned about gay rodeo and started training to compete. Now, it is a central part of his life. And those red and green Jell-o shots he’s hawking have an important role to play—Siekkinen is raising funds to revive the San Diego Gay Rodeo, a once-raucous annual event that hasn’t taken place in 14 years.

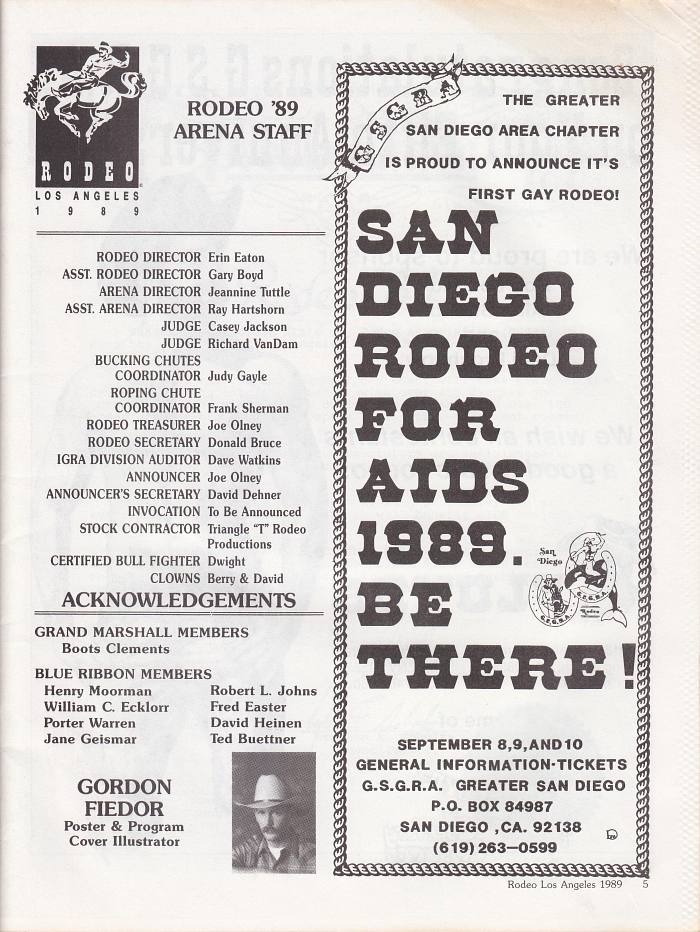

San Diego’s first Gay Rodeo was held in 1989. It continued annually up until 2010, when low membership caused it to shutter. The rodeos are completely volunteer-run, so without actively recruiting members and training new leadership, “you don’t have enough critical mass to keep going,” Siekkinen explains.

But Siekkinen believes now is the perfect time for the event to return to our city. Mainstream culture has a renewed interest in the Western aesthetic: Cowboy boots are trending, Yellowstone is streaming, and pop stars have started releasing country songs. “Right now, we’re in an upswing,” Siekkinen says. “You can just feel it.”

Longtime San Diego resident Tim Lowry attended the first-ever San Diego Gay Rodeo. “It was in Lakeside, and we were all worried about getting beat up,” he recalls. But that didn’t stop him from attending. There was too much fun to be had. Thousands of people packed an event hall at the rodeo, line dancing. “I loved me some cowboys and a twirl across the floor,” Lowry says.

What makes a gay rodeo different from a “straight rodeo?” Well, beyond the traditional roping and rough stock competitions, there are events you just won’t find anywhere else—like Steer Decorating, in which a pair of competitors must tie a ribbon to a steer’s tail, or Goat Dressing, in which contestants must wrestle a goat into a pair of tighty-whities and race back across the finish line before the underwear falls down. Then there’s the Wild Drag Race, where a participant has to jump on the back of a steer dressed in full drag. “It’s pure chaos,” Siekkinen says.

But it’s not all horseplay. Another integral aspect of the event is charity. America’s first gay rodeo, held in Reno in 1976, raised money for a Thanksgiving dinner at a home for the elderly, and subsequent rodeos have donated their profits to muscular dystrophy and HIV research, among other social needs.

“Our rodeos aren’t just for the LGBTQ community,” Siekkinen says. “I like to say they’re for anybody who’s not an asshole.” In May, one of the bull riders at the Las Vegas Gay Rodeo made his gay rodeo debut after only competing in traditional rodeos. He joined to get involved in the LGBTQ community and support his 13-year-old child who had come out as non-binary. He won the Sportsmanship Award by a landslide, Siekkinen remembers.

Siekkinen isn’t the only one striving to bring the gay rodeo back to town. Tessa Trujillo is working the crowd at The Loft, charming customers and delivering shots. Her voice carries across the patio, punctuated by an infectious laugh. “I’m a people person,” she says.

Trujillo has spent all her life in San Diego. “My family has been in California since before there was a California,” she tells me. Her grandfather was a cattle farmer. Like Siekkinen, she found her way into the gay rodeo circuit in recent years. “I’ve been to straight rodeos,” she says. “But I never felt at home.”

When she attended a gay rodeo in Scottsdale, she became hooked. She was crowned Miss Palm Springs Hot Rodeo in 2022 and Miss Golden State Gay Rodeo in 2023. But she wanted her hometown to experience the same energy and community. “I got this urge,” she says. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna bring this back to San Diego.’”

Trujillo has stayed true to her word. She has thrown herself into planning, recruiting members, and fundraising––she orchestrates pool tournaments, raffles, barbecues. “It’s a lot of work, but I love it,” Trujillo says. “I’m good at it.”

This year, Trujillo became the first-ever Mx. Golden State Gay Rodeo, a new distinction that Siekkinen helped establish in an effort to make GSGRA more inclusive. The pre-existing royalty categories were Mr., Ms., Miss, and MsTer, the latter two awarded to drag queens and kings, respectively.

PARTNER CONTENT

At the annual IGRA convention, Siekkinen proposed adding a Mx. title. He had noticed he wasn’t seeing a lot of non-binary and gender-nonconforming individuals in the rodeo community. “I want everybody to know they’re welcome,” he says. “We need to make sure we’re not stuck in the past. We have to evolve and change and bring younger people in.” The committee took a vote and it passed unanimously.

Trujillo and Siekkinen are hoping to revive the San Diego Gay Rodeo as soon as 2025. There are many steps to the process: graduating from a club to a chapter, becoming a 501(c)3, and raising a lot more money. But Siekkinen is optimistic. “Those early rodeos were wild,” he says. “That’s why so many people would come—because it was such an experience. To recapture that, we have to look to the future and make sure we are part of it.”