Abu Bakr, a 21-year-old Turkish mechanical engineering student turned asylum-seeker, speaks to me through the border wall near San Ysidro. He’s being held by Border Patrolin one of the two open-air detention sites in San Diego County–this one sits between the two border walls.

“My mother’s friend said, ‘If you go to America, […] you have your rights. If you are afraid that someone is following you and your life is in danger, they accept you there,’” he tells me.

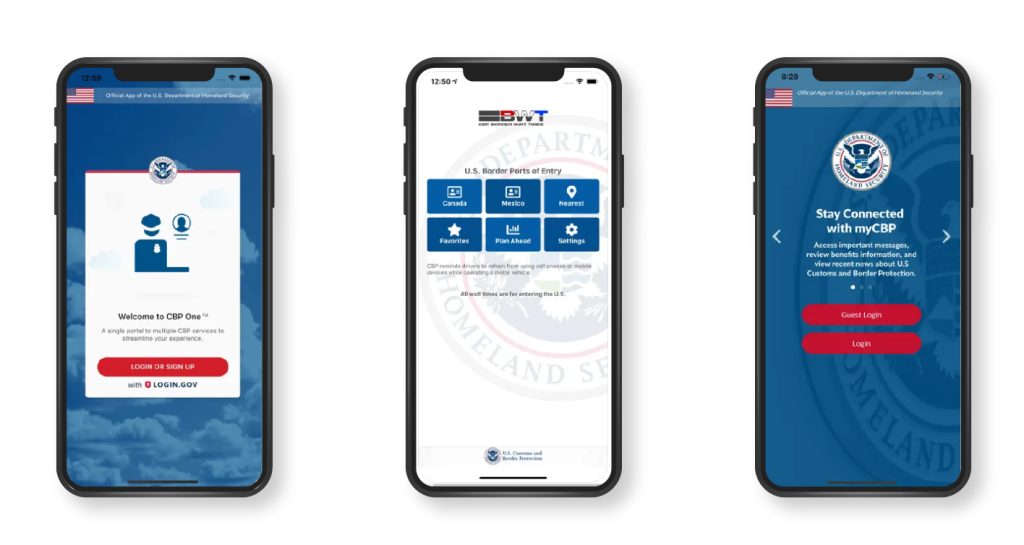

Abu Bakr wears round hipster glasses and has an iPhone in his pocket—a device he used to try to get an appointment to request asylum through the CBP One app. Right now, CBP One is virtually the sole means of accessing asylum—a right recognized by both international law and US law—but the app is proving to be a nightmare for both migrants and advocates at the border.

“[The CBP One app] didn’t work, so we chose this way,” Abubakr says. By “this way,” he means crossing the border without permission, outside of the official ports of entry.

Migrants like Abu Bakr who cannot figure out the app, wait, or know about it often find the gaps in the primary border wall to go through, then turn themselves in to the Border Patrol.

“They have no other option if they want to seek asylum,” says Hollie Webb, a supervising attorney at Al Otro Lado (AOL), a nonprofit that helps migrants navigate the asylum system. “Because if they go to a port of entry, which they have a legal right to do, they will almost 99 percent of the time be turned away.”

The AOL team and their clients, alongside another immigration-focused nonprofit called Haitian Bridge Alliance, are currently embroiled in a class-action complaint against California’s Southern District. AOL attorneys argue that, in turning asylum seekers away at ports of entry, the United States is violating international and domestic law.

The cell phone app CBP One has been around since 2020. In May of 2023, however, the Biden administration made it the only way people could ask for asylum in the United States, just as the controversial, Trump-era Title 42—which allowed speedy deportations of migrants during Covid—was phased out.

At the time, officials touted the software as the solution for longtime problems with the US immigration system. “[The app] will expand the number of appointments, allow for additional time, [and] prioritize those first registered,” Customs and Border Protection announced in a press release.

But migrant advocates at the border say the app has proven problematic. “People here in Tijuana are having to wait for three [or] four months or longer to get an appointment,” Webb explains. Before the app and Title 42, people could come to any Port of Entry and ask for asylum then and there, without having to wait.

And there are other issues: CBP One is only offered in three languages (English, Spanish, and Haitian), and is reportedly riddled with error messages and bugs, crashes often, can only be used in Mexico north of Mexico City, and requires migrants to have an address in the US.

Additionally, Webb sees a clear discrepancy with the treatment of thousands of Ukranian asylum-seekers who arrived in Tijuana in 2022–while Title 42 was still in place– and were processed as they reached the San Ysidro Port of Entry.

“The administration and CBP are always talking about the lack of capacity, and that’s why they can’t process the asylum seekers,” she says. “But we saw the year before last with the Ukrainians that they processed up to 1,000 asylum seekers just at the San Ysidro port of entry. Suddenly, when the asylum seekers aren’t white, there’s a problem with capacity.”

A 10-minute drive from the open-air detention site where I speak to Abukabr, I meet Jehovana de los Ángeles Rangel Serrano. She is sitting on the floor holding her six-month-old baby in front of the Ped West port of entry in San Ysidro, among 60 or so other migrants who were able to get one of the prized appointments and put in their asylum petitions with CBP. “We waited a month-and-a-half in Mexico,” she says. “But that was just lucky.”

Rangel Serrano’s family had to register through the app four times before finally securing an appointment at the border. “We waited in Mexico City, then Monterrey, Saltillo, and Tijuana—everywhere really!” she recalls.

Her husband and older child are beside her, looking tired but happy. They are Venezuelan, same as many other families in their group. Just past noon, a bus arrives to take them to a shelter, where they will wait—yet again—to board a plane to their final destination. In Rangel Serrano’s case, that’s Philadelphia, where her brother lives.

Migrants in this group seem satisfied with the existing asylum channels. Webb tells me that most migrants who get an appointment through CBP One feel good about it; that the petition process was shorter than they expected.

But back at the open-air detention site between the border walls, Abu Bakr sits on a camping chair. He came alone with his mother, but in his group are two other women, one with two small children and another with four, including a baby who is currently sleeping peacefully on her lap.

“We have been waiting here since 3 a.m.,” he tells me. He explains that his family received death threats after his grandfather, a government official, passed away. “In Tajikistan, I was with my mother when the police came and they put restraints on her. They asked her for money,” he recalls.

PARTNER CONTENT

Looking at the makeshift camp made of blue tarps and easy-up tents provided by migrant advocates, I ask him if this is what he imagined when he decided to travel to the US.

“I was ready for everything for the safety of my mother,” he answers.