On a chilly Saturday morning, Pam Orr drives to Campus Point at the University of California, Santa Barbara, surfboard in her backseat. It’s been a stormy few days. She and her five friends have been texting all morning about tide reports, wave height, and swell direction, unsure if surfing is a good idea.

It’s the first time in a few months the women’s schedules have aligned. So they go.

By the time Orr rolls up in the palm-tree lined parking lot, across from dorms where she went to college over 40 years ago, the rest of the women are already there, including Vanessa Kirker, who grew up in North San Diego County. She went to Moonlight Beach every summer but never touched a surfboard until she was her 60s.

Marianne McPherson, 68, is there, too, with her red matte lipstick and a torn rotator cuff. Her doctor told her not to surf, and if she’s honest with herself, she’s dreading this. Nevertheless, she stands by her car (emblazoned with a ‘Bichhin’ license plate) on an artificial grass changing mat Orr gifted her.

Orr, meanwhile, is “vibrating stress.” A 63-year-old third grade teacher—her classroom door has the kid’s names written on bright surfboard cut-outs—her week consisted of incessant rain that kept her students stuck inside. She still has a pile of essays to grade. She shouldn’t be here. But the chit-chat is a distraction, and she welcomes it.

“I have your tennis racket.”

“Do I need my hat?”

“The booties stick, so they don’t necessarily land where I want them to land.”

Gauzy fog lingers over the ocean beyond the fence, beckoning. The women unzip long, shiny bags and lay their boards down on the wet cement. They pull sweatshirts over their heads and begin the transformation. Ann Wilbanks, who has dirty blonde hair “proudly going silver,” asks if the wetsuit with neon blue calves Orr takes out is new.

She nodes and jokes. “It’s baggy on me. I was like, ‘Have I shrunk?’”

The women slip salt-soaked wetsuits onto bodies that have skied mountains, cycled hundreds of miles, raced sailboats, swum in triathlons, birthed babies, and cradled grandbabies, pulling and tugging until the spongy neoprene sticks like a second skin.

Orr, Arkin, and Kirker wait patiently for a wave.

Go to any coastline, and you’ll find that women have continued to reclaim their place in the surfing lineup. Look closer, and you’ll see an abundance of laugh lines on more and more faces of women lured by the beauty and thrill of the ocean.

It’s hard to say how many older women surfers there are in California. Nearly a third of the 60 members of the San Diego chapter of The Wahine Kai Women’s Surf Club are 50-plus—a number that tracks with their three other West Coast chapters. The San Diego Surf Ladies Community, a former nonprofit that’s now a Facebook group, also has its fair share. Co-organizer Alexia Bregman, 51, says there’s a circularity that comes with surfing older.

“There’s a wildness to the ocean that we don’t have in our lives anymore. The wind is in your face and the water is spraying you and the sense of play from being a child comes back,” she says. “It invigorates and reawakens something in your cellular being.”

Despite growing up in the ’60s in the heyday of Gidget, the movie-turned-television-series about a sassy teen girl surfer, surfing came much later for the Santa Barbara women. Careers and children took precedence, with some watching instructors push their kids into the waves instead.

After her children grew up and she had more free time, Orr, for one, finally decided it was her turn. She discovered Salt Water Divas, a Santa Barbara group created by then-46-year-old Toyo Yamane-Peluso in 2012 with the goal of getting more local women into surfing. To date, there are more than 600 members. Doug Yartz, owner of the shop Surf Country, teaches most of the lessons.

San Diego Wahine Kai members hit the waves in Pacific Beach.

Orr took her first lesson on Mother’s Day eight years ago. She remembers second-guessing her decision shortly after signing up. “[I worried,] What will people think of this older woman going out and wanting to surf? Then I saw this older man with white hair, and he got a surfboard and walked down to the beach,” she says. “I thought, Well, nobody thinks twice about an older man.”

The second lesson went poorly, and she almost didn’t continue. A “Never Give Up” sticker she saw on a car afterward led her to the friends she regularly surfs with now: Nancy Arkin, a retiree from the US Forest Service whose daughter is a global surf photographer; McPherson, a mid-level manager at an aerospace company who always wanted to surf but grew up near Oregon’s frigid waters; and Mary Johnson, a retired physical therapist who is dedicated to keeping active.

They were a formidable foursome for a few years. The group expanded when two lawyers who changed careers joined later: Kirker, a therapist who often saw surfers while open water swimming and thought, I could do that; and Wilbanks, an art and antique dealer from Connecticut who spends half the year living near her grown kids, including a daughter who encouraged her to surf.

“There’s nothing I’ve ever done athletically that gives you that feeling of power and speed [like surfing],” Wilbanks, 65, says. “It’s like dancing on water.”

The women all took lessons through Salt Water Divas and gravitated toward each other because of their similar ages. They found they also shared athletic backgrounds, a level of comfort in the water, and another trait, perhaps the most important: stubbornness.

“We were taught to accept the world as it sees us,” Kirker, 66, says. “Learning to surf in your 50s and 60s is not accepting the world as it sees you but accepting you for yourself.”

Vanessa Kirker, Pam Orr, and Arkin suit up in the UC Santa Barbara parking lot before heading down to the water.

The parking lot this morning is nearly empty. Campus Point is known for being beginner-friendly, often crowded with college kids, but every now and then the women have had to contend with jerks—teenage boys, mostly, who try to take every wave. Often, they’ll move to another spot or let the boys know it’s time for them to share, with letting a little of their annoyance come through in their voices.

It’s not always the boys, though. Once, at C Street, a more aggressive and advanced surf spot in Ventura, a woman yelled at Kirker for accidentally dropping in on her. Kirker apologized, but the woman still berated her, shouting, “What are you doing? You don’t belong here.”

Kirker said nothing, got out of the water, and cried. As a family law litigator for 30 years in a profession dominated by men, she’d had enough of feeling like she didn’t belong. She didn’t want to surf angry, and her board sat in her garage for four years until the pandemic started—around the time she shifted careers, which she attributes to surfing. She was tired of fighting with people.

Today, the wet weather holds the promise of fewer people. The women wax their boards, slip on booties speckled with grains of sand, and, one by one, head to the beach path. Their wetsuits squeak as they walk past the humble Marine Science Institute and over a driftwood-laden rocky shore. Johnson, the oldest of the crew at 71, has wasted no time snapping on a surf cap over her short, white hair and is the first one in the water.

Arkin brings up the rear, holding a longboard with a hook she’s attached so she can grip it better. Her forearm has a fish tattoo with a Buddhist design for freedom. She’s headed towards Poles, a left break named after three poles that used to mark an underground water intake valve. A bonus, they joke later, is that it’s out of range of the surf camera that continuously streams on a giant TV in Yartz’s shop.

Arkin paddles out, the whoops and hollers from her friends already mixing with the screeching of the seagulls.

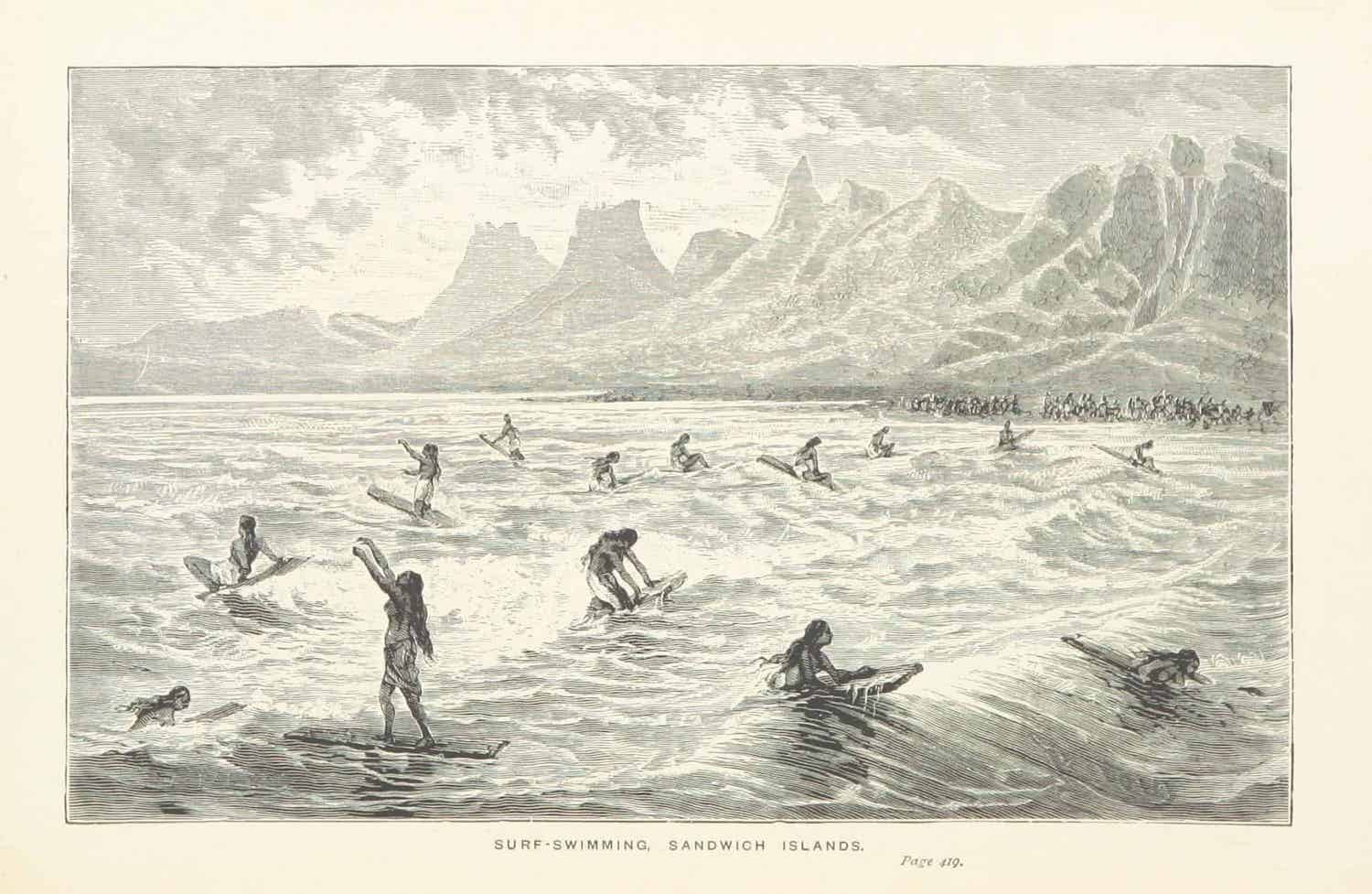

Women have been surfing for a long time—as far back as the 17th century in Hawaii and other Polynesian islands (the daring Princess Kelea of Maui was legendary)—but you wouldn’t know it if you looked at any surf magazines before the ’70s, when women got their own professional circuit. Even then, it took two decades for lifestyle brands to embrace female surfers—usually ones that were blonde and conventionally attractive—in their marketing campaigns.

Representation in the sport has long skewed young, white, and male, but that’s changing. Women surfers who identify as queer, BIPOC, and curvy have led the way in advocating for a more inclusive surf culture.

Older women surfers are a smaller subgroup, though no less loud. When they’re not chasing waves, they’re in Facebook groups and Reddit threads, piping up whenever someone asks, “Am I too old to surf?”

The Santa Barbara women might still be outliers, but they say it’s becoming more and more common to see others who look like them—although it’s not something they fixate on. “I forget about the age thing when I’m in the water,” Johnson says, adding that she does get a kick out of surprising people.

San Diego Wahine Kai member Carla Verbrugghen catching a wave at Tourmaline Surf Park.

Letting go and living in the moment is one of the draws of surfing. But it’s also a practical strategy, as timing is everything. No wave is ever the same. Then there’s the added variable of age, which comes with decreased flexibility or slower reactions that can make it challenging to pop up, ride a wave for a while, and try out fun tricks.

“We don’t have a pop up. We have a lumber up,” McPherson likes to joke.

The women have all experienced their share of injuries—broken toes and fingers, head gashes, face cuts and bruises—but it’s not enough to stop them.

Though gravitate toward cruisy waves, aware of their bodies’ limits, they are still addicted to the excitement of getting better and better each year. The friends might never go pro, but they have certain advantages that age brings: acceptance, patience, and unapologetic enjoyment of something they can claim as theirs after a lifetime of caring for others.

“We’re like these little lights out there communing in the surf. We all respect and honor each other’s individual experience. And we’re not in relation to anyone. We’re not someone’s mother, someone’s wife, someone’s daughter,” Kirker says. “It’s really freeing.”

Arkin and Kirker ride to shore.

The waves are better than they expect this morning. The water is glassy, meaning there’s little wind, the smooth sheen ideal for surfing.

The women are the only ones in the water except for two surfers who are far enough away to leave them alone. Johnson paddles to catch a wave. Kirker, the crew’s most vocal cheerleader, yells: “Go left, go left!” Johnson stands up, compact and still as a statue, and rides the wave nearly all the way to the shore. Kirker hollersl “Woooohoooo!”

A big part of the joy of surfing is being with each other. Some of it is a matter of safety, knowing that if they wipe out or have the wind knocked out of them someone will be there to help. But it’s the camaraderie that keeps them going out together week after week; everyone else knows to make plans around their surf schedule.

“There’ll be days when I don’t catch anything,” McPherson says. “But the enjoyment of being together and celebrating your own successes with an audience of people who love you, and celebrating their successes—it’s double the adrenaline.”

Nearly all are partnered, with husbands or boyfriends, but most of their men don’t share the stoke. Surfing has become a defining feature of their identities, met with a combination of raised eyebrows and subtle boasts. McPherson’s cousin will often introduce her to others and say, “This is Marianne. She surfs every day.” (She doesn’t.)

Now McPherson straddles the back of her board, lipstick still intact. Kirker is nearby and waits with the others for a good swell. Orr also sits close, her brown-blonde bob she has yet to dye now dark from the saltwater. The rocking of the ocean relaxes her shoulders.

“I just feel like the weight’s off,” she says.

“It’s because I’m here,” Kirker says. Orr laughs.

In an instant, the calm is broken. Orr spots a potential wave. She lies down on her board, turning its nose around toward shore. Everyone cheers. “Go, go, go!”

Careful not to strain knees that need replacing, she pops up for a few seconds before tumbling backwards into the water. “I blew it,” she says when she’s straddling the board again. “That could’ve been a nice, long wave.”

They all flail at some point, limbs flying everywhere, boards bouncing along the whitewash. “Come on, bitches!” Kirker says one time to the waves, furiously paddling, only to have them fizzle out.

It takes a lot for everything to be in sync, and learning how to cope with failure is one of surfing’s greatest lessons. There’s joy in that, too.

“You tend to become competent in the things you do at a certain age,” Arkin says. “But what’s been really fun for me is being incompetent at something new.”

Yet Arkin and the other women are far from incompetent, catching numerous waves, a testament to the number of years they’ve taken lessons together not only at Campus Point, but at surf clinics in Costa Rica and Mexico. They’ll also travel around California together—every Memorial Day for the past eight years, they’ve headed down to Beacons in Encinitas.

Just today, they’ve been out for nearly two hours. Onshore, more people are strolling along the nearby cliffs, while college kids in wetsuits stand at the edge of the water, about to paddle out.

“I’m getting cold,” Arkin says, metal in her finger from a surf injury stiff. They all agree to stop soon.

As they wait for the last few waves, Kirker hums The Monkees theme song. “There’s just something about the ocean that makes me want to sing,” she adds.

Nancy Arkin carries her board at Campus Point in Santa Barbara, California

The women carry the boards back to their cars. The parking lot is busier, and a 20-something-year-old wearing a UCSB sweatshirt walks by with an older couple, presumably his parents. One of them sees the friends pulling terry cloth surf ponchos over their heads and smiles. They don’t notice.

There’s talk of going to Starbucks afterwards. Over coffee and chai, they will laugh at obnoxious men on dating sites, reminisce about raising athletic children, and share their personal surfing stats from the Dawn Patrol apps they all have on their Apple watches. (Johnson had 11 waves, with one at 20 mph, nearly twice the average speed.) And they’ll make plans to go surfing again tomorrow.

For now, the focus is on getting warm. The clouds have parted. “Here’s your sunshine!” Kirker says.

“Well, I had more good biffs today,” Arkin says, brushing her wispy hair.

Kirker won’t hear it. “I thought you did fine.”

San Diego Wahine Kai members catch a party wave.

Today, they’ve emerged both tired and triumphant, the ocean leaving them breathless at times. When they go home, they will be unable to fully articulate the feeling—of being themselves, of being together—but it is one they will continue to chase. Because with so much life still ahead of them, they unabashedly want more. Since she began surfing, “my whole world is better,” Kirker says.

PARTNER CONTENT

She sits down on the side of her white cargo van with a “Soul of a Mermaid, Mouth of a Sailor” sticker and pours a jug of water over her head. McPherson towels off, her shoulder fine, at least for right now. Wilbanks helps Johnson slither out of her wetsuit.

Orr is the last one to return. In the back of her mind are the essays she still needs to grade, but they don’t seem as urgent. And, like the rest of her friends, she doesn’t ever foresee a time when she’ll stop surfing. “When I started, I thought, I’ll probably be able to do this for, like, five or six years, and then I won’t be able to do it anymore. But look at Mary. She’s my hero,” she says. “And now I think, God, I hope I can keep surfing as long as her.”