You can see time here, if you pay attention. Bronze fingernails of various lengths.

Local dirt pressed into a layered plinth like Earth’s strata. A bronze object steadily patinaing to green. They all trace the histories—personal, political, geological—by which Kelly Akashi is gripped.

Akashi, a 40-year-old Los Angeles–born artist, began her career in analog photography before exploring old-world craft techniques like glass-blowing, metal and silicon casting, and rope-making. Formations, which made stops at the San Jose Museum of Art and Seattle’s Frye Art Museum before touching down at La Jolla’s Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD), is Akashi’s first major solo exhibition.

A crystal cast of the artist’s hand rests on a stone from Poston, Arizona, wearing a ring that once belonged to Akashi’s grandmother.

More than three dozen of her pieces from the last decade sprawl across five galleries, opening with a bronze sculpture of two intertwined tumbleweeds. The object is modeled after real tumbleweeds Akashi photographed in Poston, Arizona, where her father, then a child, was confined in a Japanese-American internment camp during World War II. “It’s a monument to something ephemeral,” says Jill Dawsey, MCASD’s senior curator.

Such monuments from Akashi’s pandemic-era trip to Poston stipple the exhibition. Seemingly mundane natural objects—branches, pinecones, stones—become stark reminders of what they or their progenitors witnessed.

Akashi arranges her pieces in “small [thematic] constellations,” Dawsey says. As a result, “her works start to talk to each other.”

Pieces crafted prior to Akashi’s Poston series reflect the same impulse to commemorate the fleeting, even as it slips away. Hands—Akashi’s own—are among the dominant symbols in Formations, and, because Akashi intends to cast her hands every year for the rest of her life, they form an indelible record.

Throughout the galleries, fluttering, tactile things—fingers, leaves—are stilled, frozen in bronze and crystal. Notoriously rigid materials like glass take on organic movement, draping like fabric, curving like bodies.

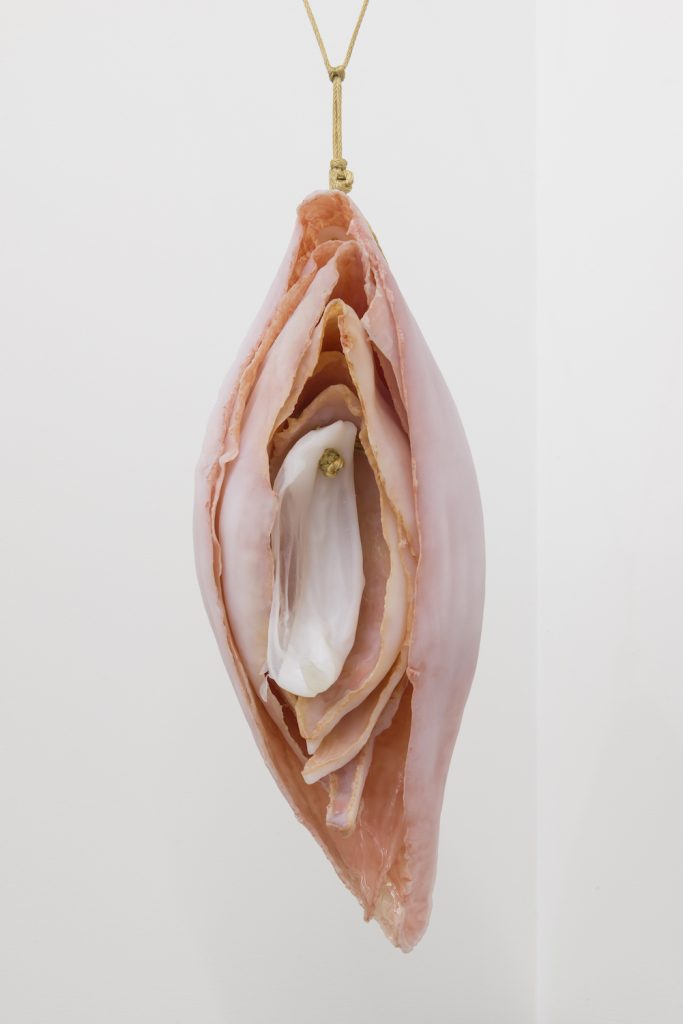

Akashi used dried onion skins to model this larger-than-life piece, titled Eat Me.

But even when movement is arrested, there’s a hunger to Akashi’s work. The hands she casts are rarely truly at rest. Instead, they clutch, climb, tangle with rope. One helps suspend, by threads, a glass orb on the opposite side of a gallery wall—so, though they’re integrally connected, “we have to rely on our own internal mapping to picture the two objects together,” says Zachary Abramson, MCASD’s lead educator. According to Akashi, the orb contains consciousness. The question becomes, then, what unseen force might be holding you?

Akashi calls “asking the questions” integral to her art-making. But, because of her attention to craft, her process of creation—an object’s formation—is just as important as its conceptual lean.

Akashi painstakingly replicated a real plant to craft the bronze Summer Weed.

Take Summer Weed, a deceptively simple-looking sculpture of a lanky plant that took two years to complete. Akashi initially allowed a weed to grow tall in her backyard. She plucked every leaf from it, then cast the stem in bronze. Afterward, she replicated each leaf, cutting them out in copper foil, and applied them to the stem in the same pattern as the original plant. “I wanted the way I made this sculpture to be an important part of its story, so I made it as difficult as possible for myself,” she says.

The results of her meticulousness are all exquisitely beautiful, and, while her larger pieces are naturally the most arresting at first glance, it’s the smaller works that don’t seem to let me go. Dawsey agrees: “[The] intimate pieces, they seduce you and pull you in,” she says.

PARTNER CONTENT

In one room, above six woman-shaped glass vessels, hangs a quartz bell that, when rung, emits a low, resonant frequency designed, Akashi says, “to reach inside the viewer.” The lines on her bronze palms, the twist of delicate glass flowers—they have the same effect. They tug at your chest, invite you to pause and wonder what changed when you were moving too fast to notice it.

MCASD will host Kelly Akashi for an artist talk on Jan. 18. Formations is on view through Feb. 18.